Friedrich Engels

[7][8] At the age of 13, Engels attended secondary school (Gymnasium) in the adjacent city of Elberfeld but had to leave at 17 due to pressure from his father, who wanted him to become a businessman and work as a mercantile apprentice in the family firm.

In the book, Engels described the "grim future of capitalism and the industrial age",[30] noting the details of the squalor in which the working people lived.

[39] In Paris, Marx and Arnold Ruge were publishing the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher, of which only one issue appeared (in 1844), and in which Engels wrote Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy.

"[40] Marx adopted Engels's idea that the working class would lead the revolution against the bourgeoisie as society advanced toward socialism, and incorporated this as part of his own philosophy.

Carl Wallau and Stephen Born (real name Simon Buttermilch) were both German immigrant typesetters who settled in Brussels to help Marx and Engels with their Communist League work.

Criticising his involvement in the uprising she states in a 5 December 1848 letter to Friedrich that "nobody, ourselves included, doubted that the meetings at which you and your friends spoke, and also the language of (Neue) Rh.Z.

Starting with an article called "The Magyar Struggle", written on 8 January 1849, Engels, himself, began a series of reports on the Revolution and War for Independence of the newly founded Hungarian Republic.

[59] Engels's articles on the Hungarian Republic became a regular feature in the Neue Rheinische Zeitung under the heading "From the Theatre of War"; however, the newspaper was suppressed during the June 1849 Prussian coup d'état.

[67] As to his "short-sightedness", Engels admitted as much in a letter written to Joseph Weydemeyer on 19 June 1851 in which he says he was not worried about being selected for the Prussian military because of "my eye trouble, as I have now found out once and for all which renders me completely unfit for active service of any sort".

[72] Upon his return to Britain, Engels re-entered the Manchester company in which his father held shares to support Marx financially as he worked on Das Kapital.

[81] Marx also borrowed Engels' characterisation of Hegel's notion of the World Spirit that history occurred twice, "once as a tragedy and secondly as a farce" in the first paragraph of his new essay.

As early as April 1853, Engels and Marx anticipated an "aristocratic-bourgeois revolution in Russia which would begin in "St. Petersburg with a resulting civil war in the interior".

Later editions of the text demonstrate Marx's sympathy for the argument of Nikolay Chernyshevsky, that it should be possible to establish socialism in Russia without an intermediary bourgeois stage provided that the peasant communes were used as the basis for the transition.

[92] Similarly, Tristram Hunt argues that Engels was sceptical of "top-down revolutions" and later in life advocated "a peaceful, democratic road to socialism".

The reason for Engels' caution is clear: he candidly admits that ultimate victory for any insurrection is rare, simply on military and tactical grounds".

Engels's stance of openly accepting gradualist, evolutionary and parliamentary tactics while claiming that the historical circumstances did not favour revolution caused confusion.

[96] On 1 April 1895, four months before his death, Engels responded to Kautsky: I was amazed to see today in the Vorwärts an excerpt from my 'Introduction' that had been printed without my knowledge and tricked out in such a way as to present me as a peace-loving proponent of legality [at all costs].

[99] He had to provide it with structure and develop its lines of thought, so that the second and third volumes of Capital are effectively joint in authorship and its content (except for the extensive forewords added by Engels) cannot be attributed exclusively to either author.

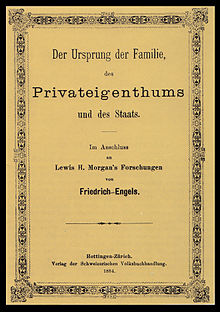

[100] While the task of editing Capital forced Engels to abandon his unfinished Dialectics of Nature, he still completed two other works of his own in the years following Marx's death.

[108] Of Engels's personality and appearance, Robert Heilbroner described him in The Worldly Philosophers as "tall and rather elegant, he had the figure of a man who liked to fence and to ride to hounds and who had once swum the Weser River four times without a break" as well as having been "gifted with a quick wit and facile mind" and of a gay temperament, being able to "stutter in twenty languages".

Engels favoured forming romantic relationships with women of the proletariat and found a long-term partner in a working-class woman named Mary Burns, although they never married.

[7][30]As to the religious persuasion attributable to Engels, Hunt writes: In that sense the latent rationality of Christianity comes to permeate the everyday experience of the modern world—its values are now variously incarnated in the family, civil society, and the state.

What Engels particularly embraced in all of this was an idea of modern pantheism, or, rather, pandeism, a merging of divinity with progressing humanity, a happy dialectical synthesis that freed him from the fixed oppositions of the pietist ethos of devout longing and estrangement.

[7]Engels was a polyglot and was able to write and speak in numerous languages, including Russian, Italian, Portuguese, Irish, Spanish, Polish, French, English, German and the Milanese dialect.

[...] In their scientific works, Marx and Engels were the first to explain that socialism is not the invention of dreamers, but the final aim and necessary result of the development of the productive forces in modern society.

[93] Tristram Hunt argues that Engels has become a convenient scapegoat, too easily blamed for the state crimes of Communist regimes such as China, the Soviet Union and those in Africa and Southeast Asia, among others.

Hunt writes that "Engels is left holding the bag of 20th century ideological extremism" while Karl Marx "is rebranded as the acceptable, post–political seer of global capitalism".

[112] While admitting the distance between Marx and Engels on one hand and Joseph Stalin on the other, some writers such as Robert Service are less charitable, noting that the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin predicted the oppressive potential of their ideas, arguing that "[i]t is a fallacy that Marxism's flaws were exposed only after it was tried out in power.

Originally published in German and only translated into English in 1887, the work initially had little impact in England; however, it was very influential with historians of British industrialisation throughout the twentieth century.

In the course of replying to Dühring, Engels reviews recent advances in science and mathematics seeking to demonstrate the way in which the concepts of dialectics apply to natural phenomena.