Compagnie Générale Transatlantique

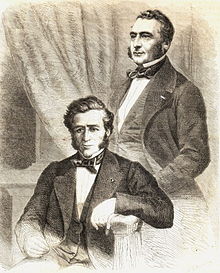

Established in 1855 by the brothers Émile and Issac Péreire under the name Compagnie Générale Maritime, the company was entrusted by the French government to transport mails to North America.

Weakened by World War II, the company regained its fame in 1962 with the famous SS France, but the ship suffered major competition from air transport and was retired from service in 1974.

The quality of services aboard, such as that of meals and wines, had attracted wealthy clientele, including Americans at the time of the Prohibition in the United States.

With the construction of its first six ships having begun abroad (in particular SS Washington, the first liner built for the New York route), the Péreires were well aware of the prices charged by foreign shipyards.

[13] The Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the uncertain beginnings of the French Third Republic further reduced the traffic and profits of the transatlantic route while competition from other shipping companies increased.

Slightly larger, and, above all, faster than its predecessors (19 knots on average), it however remained below the performance of its competitors (it narrowly failed to conquer the Blue Riband).

Nevertheless, it was built at the right time to allow the replacement of the boilers of SS La Normandie, and especially to take advantage of the World Columbian Exposition to be held in the United States in 1893.

[23] Added to this were several maritime disasters, notably the abandonment at sea of SS City of Saint-Nazaire (1897) and the disappearance of the cargo ship Pauillac which was later revealed to have been purchased at a low price from another company and was in poor condition.

In response, the company posted inflammatory posters on the quays, mobilized the anti-strike "yellow" union, and demanded that the police protect the freedom to work.

The whole Left mobilized, from the socialist Jean Jaurès to the anarchist Sébastien Faure, including the trade unionist Georges Yvetot and Paul Meunier.

[48] After the war, the flagships of the company, in particular Paris, benefited from an influx of migrants from Central Europe, while winning the loyalty of a wealthy clientele.

[51] The company experienced a success and massively increased its clientele by taking advantage of the Prohibition in the United States, which pushed American passengers to travel on French liners in order to consume alcoholic beverages.

[57] The following year, significant competition began against the Cunard Line and its liner RMS Queen Mary, it and Normandie having similar level of performances.

The Île-de-France and several other ships benefited from the resistant fiber of company's General Staff, which managed to make them sail on behalf of the forces of Free France and the United Kingdom.

Of the large liners, only the Île-de-France survived (the Paris caught fire shortly before the conflict), and it had to undergo a major refit after its war service.

Its managing director, Edmond Lanier, was expected to take over, but it was the president of Messageries Maritimes, Gustave Anduze-Faris, who took up the post, before himself retiring in 1963.

However, for President Lanier, the defense of SS France as a symbol of the company was essential, while the ship's operational deficits widened from the mid-1960s onward.

[85] This route also gradually became very popular, especially after World War II, with the company's freighters, which brought back to France large quantities of rum, sugar and bananas.

[88] Although the activities of the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique had always been centered around the oceans, the company could not ignore the technological progress in the area of civil aviation made at the beginning of the 20th century.

Thus, in 1928, John Dal Piaz had a seaplane catapult installed on SS Île-de-France, which enabled mails to be delivered to their recipients one day before the ship's arrival at its destination.

[96] At that time, passengers still showed some suspicion towards steam propulsion, however, and until the 1890s all of the company's ships were fitted with masts capable of carrying sails.

In 1965, SS France became the first liner to transmit by satellite the electrocardiogram results of one of its passengers, allowing a surgery to be conducted at sea in collaboration with European and American teams.

[104] The CGT, being far away from major migratory routes, and restricted in the development of its ships by the size of the port of Le Havre, was not really able to benefit from the financial windfall from emigrants, as the German and British companies did.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the company's liners thus developed a reputation for being sumptuous ships, where the French art of living — especially gastronomy and wine — reigned supreme.

On November 22, it collided with the iron clipper Loch Earn and sank in about ten minutes with the loss of 226 lives; only 61 passengers and 26 crew members survived.

The inexperience of American sailors recently assigned to the liner effectively rendered the numerous fire protection devices aboard ineffective.

[62] The company also lost SS Lamoricière in the war due to a storm en route between Algiers and Marseille in 1942, killing nearly 300 people and leaving 90 survivors.

[120] In its 120 years of existence, the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique has acquired a special place within the French shipping industry, and a particular prestige with foreign customers, especially Americans.

[124] SS France of 1962 served as the setting for the final scene of the French film The Brain with Bourvil and Jean-Paul Belmondo, as well as for Gendarme in New York, with Louis de Funès.

[132] Other future projects continue to highlight the heritage of the company, such as the planned building of a new ship named France by Didier Spade.