French protectorate of Tunisia

The Tunisian government's budget was quickly cleaned up, which made it possible to launch multiple infrastructure construction programs (roads, railways, ports, lighthouses, schools, hospitals, etc.)

and the reforms that took place during the Beylik era contributed to this,[8] which completely transformed the country above all for the benefit of the settlers, mostly Italians whose numbers were growing rapidly.

In 1859, Tunisia was ruled by the Bey Muhammad III, and the powerful Prime Minister, Mustapha Khaznadar, who according to Wesseling "had been pulling the strings ever since 1837.

Economic conditions deteriorated through the 19th century, as foreign fleets curbed corsairs, and droughts perennially wreaked havoc on production of cereals and olives.

Because of accords with foreign traders dating back to the 16th century, custom duties were limited to 3 per cent of the value of imported goods; yet manufactured products from overseas, primarily textiles, flooded Tunisia and gradually destroyed local artisan industries.

Two years later France, Italy and Britain set up an international finance commission to sort out Tunisia's economic problems and safeguard Western interests.

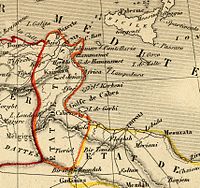

[9] To the east lay Tripolitania, province of the Ottoman Empire, which had made itself practically independent until Sultan Mahmud II successfully restored his authority by force in 1835.

[14] However, they relied on a possible British opposition to an enlargement of the French sphere of influence in North Africa (while, if anything, London was hostile about a single country controlling the whole Strait of Sicily).

The motivations of this action were provided by Jules Ferry, who sustained that the Italians wouldn't have opposed it because some weeks before France had consented to a renewal of the Italo-French trade treaty.

The events, in effect, demonstrated the irrealisability of the foreign policy of Cairoli and of Depretis, the impossibility of an alliance with France and the necessity of a rapprochement with Berlin and with Vienna, even if obtorto collo.

However, such an inversion of the foreign policy of the last decade couldn't be led by the same men, and Benedetto Cairoli resigned from office on 29 May 1881, thus avoiding that the Camera would openly distrust him; since then he de facto disappeared from the political scene.

At 4 pm, escorted by two squadrons of hussars, Bréart presented himself in front of the Bey's palace accompanied by his entire staff and most of the senior military officers.

These documents provided that the Bey continue as head of state, but with the French given effective control over a great deal of Tunisian governance, in the form of a protectorate.

Paris did not act immediately; the French parliament remained in an anti-colonial mood and no groundswell of popular opinion mandated a takeover of Tunisia.

A French consortium buying the property believed the deal had been completed, but a British citizen, ostensibly representing neighbouring landholders, preempted the sale and occupied the land (though without paying for it).

[31] In Tunisia: Crossroads of the Islamic and European World, Kenneth J. Perkins writes: "Cambon carefully kept the appearance of Tunisian sovereignty while reshaping the administrative structure to give France complete control of the country and render the beylical government a hollow shell devoid of meaningful powers.

French experts answerable only to the Secretary-General and the Resident-General managed and staffed those government offices, collectively called the Technical Services, which dealt with finances, public works, education, and agriculture.

[32] Successive Residents-General, fearing the soldiers' tendency toward direct rule – which belied the official French myth that Tunisians continued to govern Tunisia – worked to bring the Service des Renseignements under their control, finally doing so at the end of the century.

French officials hoped that their careful monitoring of tax assessment and collection procedures would result in a more equitable system and stimulate a revival in production and commerce, generating more revenue for the state.

[36] The protectorate authorities made no attempt to alter Muslim religious courts in which judges, or qadis, trained in Islamic law heard relevant cases.

According to Perkins, "Many colonial officials believed that modern education would lay the groundwork for harmonious Franco-Tunisia relations by providing a means of bridging the gap between Arabo-Islamic and European cultures.

"[36] In a more pragmatic vein, schools teaching modern subjects in a European language would produce a cadre of Tunisians with the skills necessary to staff the growing government bureaucracy.

Soon after the protectorate's establishment, the Directorate of Public Education set up a unitary school system for French and Tunisian pupils designed to draw the two peoples closer together.

[39] Following the Second Armistice at Compiègne between France and Germany, the Vichy Government of Marshal Philippe Pétain sent to Tunis as new Resident-General Admiral Jean-Pierre Esteva, who had no intention of permitting a revival of Tunisian political activity.

[citation needed] The arrests of Taieb Slim and Habib Thameur, central figures in the Neo-Destour party's political bureau were a result of this attitude.

[citation needed] The Bey Muhammad VII al-Munsif moved towards greater independence in 1942, but when the Axis were forced out of Tunisia in 1943, the Free French accused him of collaborating with the Vichy Government and deposed him.

[citation needed] From 10 August, he did not hesitate to enter into conflict with Jean-Pierre Esteva by presenting him with a memorandum grouping together 16 demands inspired by his nationalist friends.

Fearing arrest, Bourguiba spent much of the next three years in Cairo, where in 1950, he issued a seven-point manifesto demanding the restitution of Tunisian sovereignty and election of a national assembly.

In a speech in Tunis, Mendès-France solemnly proclaimed the autonomy of the Tunisian government, although France retained control of substantial areas of administration.

The next year, the French revoked the clause of the Treaty of Bardo that had established the protectorate in 1881 and recognised the independence of the Kingdom of Tunisia under Muhammad VIII al-Amin on 20 March.