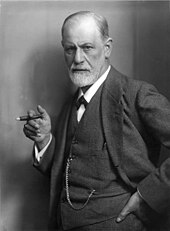

Freud and Philosophy

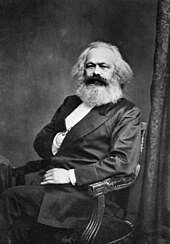

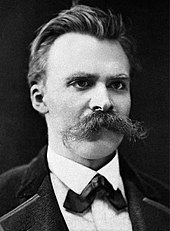

He compares Freud to the philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Nietzsche describing the trio as a "school of suspicion" and explores similarities and differences between psychoanalysis and phenomenology.

One of Ricœur's most noted works, Freud and Philosophy has been compared to the philosopher Herbert Marcuse's Eros and Civilization (1955), the classicist Norman O.

Brown's Life Against Death (1959), the sociologist Philip Rieff's Freud: The Mind of the Moralist (1959), and the philosopher Jürgen Habermas's Knowledge and Human Interests (1968).

Like Marcuse, Rieff, and Flügel, he considers psychoanalysis an "interpretation of culture", but unlike them his principal concern is the "structure of Freudian discourse".

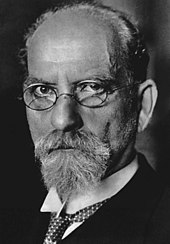

[4] Ricœur relates his discussion of Freud to the emphasis on the importance of language shared by philosophers such as Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger, schools of philosophy, such as phenomenology, a movement founded by Edmund Husserl, and English linguistic philosophy—as well as disciplines such as New Testament exegesis, comparative religion, anthropology, and psychoanalysis.

[8] He writes that Freud's examinations of dreams and related phenomena such as humor, mythology, and religion, shows that they are meaningful and concern the way in which desires "achieve speech".

[17] He discusses Freud's theories of the death drive, the defence mechanisms, homosexuality, the id, ego and super-ego, identification, the libido, metapsychology, narcissism, the Oedipus complex, the pleasure principle, the preconscious, the psychic apparatus, psychosexual development, the reality principle, sublimation, the transference, the unconscious, as well as dreamwork, Freud's seduction theory, and the method of free association.

[28] He argues that aspects of Freud's views on religion, such as his "radical questioning" of it, merit the consideration of both religious believers and non-believers, despite potential misunderstandings by both groups.

[29] Freud's hypothesis of the death instinct, put forward in Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), is criticized by Ricœur, who describes it as speculative and as resting on a limited factual basis.

He summarizes his approach as involving first examining the validity of psychoanalysis from the standpoint of epistemology, then exploring its concepts through elaborating an "archaeology of the subject".

Between them, these problems make it impossible for independent inquirers to obtain the same data under carefully standardized circumstances or for psychoanalysts to establish objective procedures to decide which conflicting interpretations might be correct.

He argues that while some psychoanalysts have tried to reformulate psychoanalysis so that it meets scientific criteria acceptable to psychologists, aspects of Freudian theory make this difficult.

He also discusses the relationship between Freud's ideas and those of the philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, comparing the role that desire plays in both men's work.

[50] Freud and Philosophy has also been praised by the philosophers Don Ihde, who nevertheless found its approach to interpretation limited by its focus on the ideas of symbol and double meaning,[51] Richard Kearney,[52] and Douglas Kellner.

He compared the structure of Freud and Philosophy to that of the philosopher Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781), and found its "methodology and prose" reminiscent of Hegel.

[60][61] Macmillan credited Ricœur with recognizing that Freud saw a close connection between the mental structures he outlined in The Ego and the Id and the instinctual theory he put forward in Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

[64] However, Freud and Philosophy has received criticism from psychologists such as Hans Eysenck, Glenn Wilson, and Paul Kline, who have attributed to Ricœur the view that psychoanalysis either cannot or should not be evaluated in terms of experimental evidence.

They argued that Ricœur espoused a form of "extreme subjectivism" which implies that psychoanalytic theories cannot be tested empirically or shown to be mistaken.

[65] Kline wrote that Ricœur might be correct that psychoanalysis cannot be dealt with through experiments based on quantifiable evidence, but argued that if he is, this shows that psychoanalytic theory is not scientific.

While Thompson praised Freud and Philosophy, he believed that Ricœur failed to resolve the "question of the scientific status of psychoanalysis" in the work.

[73] He noted that thinkers such Marcuse, Lacan, Gilles Deleuze, Jacques Derrida, and Judith Butler have produced interpretations of Beyond the Pleasure Principle irreconcilable with Ricœur's.

[80] Holt dismissed Freud and Philosophy, arguing that it was only superficially impressive, that parts of it were unreadable, and that Ricœur used vague or inappropriately metaphorical language.

At the request of the philosopher Michel Foucault, Critique published a reply by Ricœur, in which he denied the accusation and explained that he had completed the outline of his interpretation of Freud before having read Lacan.

[87] Vinicio Busacchi wrote that Tort's discussion of Freud and Philosophy was "fallacious and calumnious" and that the accusation of plagiarism against Ricœur was false.

[91] After Ricœur's death in 2005, the philosopher Jonathan Rée wrote that Freud and Philosophy was a "powerful" book that had been "scandalously neglected in France".

[93] Gargiulo described the book as "a provocative philosophical enterprise and a masterful reading of Freud" and "a text of extraordinary complexity and sensitivity".

He compared Ricœur's work to that of Rieff, and credited him with showing that "desire has a semantics" and that psychoanalysis "cannot be verified as in physical and experimental sciences".

He credited Ricœur with placing psychoanalysis in a larger historical and intellectual context and relating it to contemporary cultural trends, showing broad knowledge of philosophy, literature, and religion, and providing a useful discussion of the development of Freud's work.

He praised Ricœur's exploration of topics such as narcissism, identification, sublimation, and the reality principle, and believed that he showed the flaws of some of Freud's views on art, culture, and religion.

[99] Slater considered the book impressive, calling it the first detailed study "by a professional philosopher of the development of Freud's thought and of psychoanalytical theory in all the stages of its growth".