Frisii

The Frisii were an ancient tribe, living in the low-lying region between the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and the River Ems, sharing some cultural and linguistic elements with the neighbouring Celts.

[citation needed] During the 1st century BC, Romans took control of the Rhine delta but Frisii to the north of the river managed to maintain some level of independence.

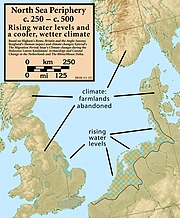

The area where the original Frisii lived was largely deserted during the Migration Period, probably due to political instability and piracy, as well as climatic deterioration and frequent flooding caused by sea level rise.

When changing environmental and political conditions made the region attractive again it was repopulated in the 5th century by Anglo-Saxon settlers from Northwestern Germany and Southwestern Denmark, who adopted the old name Frisii.

[9] In his Germania Tacitus would describe all the Germanic peoples of the region as having elected kings with limited powers and influential military leaders who led by example rather than by authority.

[11] Early Roman accounts of war and raiding do not mention the Frisii as participants, though the neighboring Canninefates (to the west and southwest, in the delta) and Chauci (to the east) are named in that regard.

Accounts of wars therefore mention the Frisii on both sides of the conflict, though the actions of troops under treaty obligation must have been separate from the policies of indigenous groups.

However, a later Roman governor raised the requirements and exacted payment, at first decimating the herds of the Frisii, then confiscating their land, and finally taking wives and children into bondage.

The propraetor of Germania Inferior, Lucius Apronius, raised the siege and attacked the Frisii, but was defeated at the Battle of Baduhenna Wood after suffering heavy losses.

[21][22] The emperor Constantius Chlorus campaigned successfully against several Germanic peoples during the internecine civil wars that brought him to sole power over the Roman Empire.

Among them were the Frisii and Chamavi, who were described in the Panegyrici Latini (Manuscript VIII) as being forced to resettle within Roman territory as laeti (i.e., Roman-era serfs) in c. 296.

The discovery of a type of pottery unique to 4th century Frisia known as Tritzum earthenware shows that an unknown number of them were resettled in Flanders and Kent under the aforementioned Roman coercion.

As soon as conditions improved, Frisia received an influx of new settlers, mostly from regions later characterized as Saxon, and these would eventually be referred to as 'Frisians', though they were not necessarily descended from the ancient Frisii.

Efforts have sometimes been made to connect this auxiliary unit with the Frisii by supposing that the original document must have said "Frisiavonum" and a later copyist mistakenly wrote "Frixagorum".

Tangible evidence of the existence of the Frisavones includes several inscriptions found in Britain, from Roman Manchester and from Melandra Castle near modern Glossop in Derbyshire.

However, Pliny's placement of the Frisiavones in northern Gaul is not near the known location of the Frisii, which is acceptable if the Frisavones are a separate people, but not if they are a part of a greater Frisian tribe.

The Byzantine scholar Procopius, writing c. 565 in his Gothic Wars (Bk IV, Ch 20), said that "Brittia" in his time (a different word from his more usual "Bretannia") was occupied by three peoples: Angles, Frisians (Φρἰσσονες) and Britons.

The eulogies of this age were intended to praise the high status of the subject, and the sudden reappearance of a list of old tribal names fitted into poetic meters is given little historical value.

In the Ravenna Cosmography, composed about 700 on the basis of antique maps and itineraries, the Danes, Saxons en Frisians ("Frisones", "Frigones", "Frixones", or "Frixos") are mentioned together several times.

The Frisians ("Fresin" or "Freisin") are (unlike the Saxons) also mentioned in 7th-century Irish lists of the 72 peoples of the world, contained in the Auraicept na n-Éces and in In Fursundud aile Ladeinn, as well as in the poem Cú-cen-máthair by Luccreth moccu Chiara.

The 12th-century Book of Leinster, obviously citing an older tradition, lists the Franks and Frisians, together with the Langobards as guests and subjects of the legendary king Cormac mac Airt.

Based on older traditions might have been the 15th-century Eachtra Thaidg Mhic Céin, which tells the story of slave raiders from the country of the Frisians ("cricha Fresen"), living on the edges of a landscape full of huge sheep and colourfull fowl.

It has been noted that Gregory of Tours (c. 538–594) mentioned a Danish king Chlochilaichus who was killed while invading Frankish territory in the early 6th century, suggesting that, in this instance, Beowulf might have a basis in historical facts.

It was written more than 500 years after the last unambiguous reference to the ancient Frisii (the Panegyrici Latini in c. 297), and at a time when medieval Frisia and the Frisians were playing a dominant role in North Sea trade.