Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti

Described by media as the "Lioness of Lisabi",[2]: 77 she led marches and protests of up to 10,000 women, forcing the ruling Alake to temporarily abdicate in 1949.

As Ransome-Kuti’s political influence grew, she took part in the Nigerian independence movement, attending conferences and joining overseas delegations to discuss proposed national constitutions.

[3] She was born to Chief Daniel Olumeyuwa Thomas (1869–1954), a member of the aristocratic Jibolu-Taiwo family, and Lucretia Phyllis Omoyeni Adeosolu (1874–1956).

Frances' mother was born to Isaac Adeosolu, who was from Abeokuta, and Harriet, the daughter of Adeboye, who was from the ancient Yoruba town of Ile-Ife.

[2]: 28–29 From 1919 to 1922, she went abroad and attended a finishing school for girls in Cheshire, England, where she learned elocution, music, dressmaking, French, and various domestic skills.

[2]: 29 Israel found work as a school principal, and he strongly believed in bringing people together and overcoming ethnic and regional divisions.

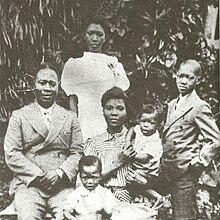

[2]: 48 Ransome-Kuti and her husband had four children: a daughter named Dolupo (1926) and sons Olikoye "Koye" (1927), Olufela "Fela" (1938), and Bekololari "Beko" (1940).

[7]: 174 In 1944 she developed a successful campaign to stop local authorities seizing rice from market women under false pretenses.

The organisation now turned its focus to fighting unfair price controls and taxes imposed on market women, with Ransome-Kuti as the AWU's president.

After a failed appeal to British authorities to remove the current Alake from power and halt the tax, Ransome-Kuti and the AWU began contacting newspapers and circulating petitions.

Undeterred, Ransome-Kuti and her fellow organisers declared that they were planning "picnics" and "festivals" instead, drawing up to 10,000 participants to their demonstrations – some of which involved altercations with police.

[2]: 81 Ransome-Kuti trained women in how to deal with the tear gas canisters sometimes thrown at them, and the AWU used its membership dues to fund legal representation for arrested members.

The incident concluded with a scuffle when Ransome-Kuti grabbed hold of the steering wheel of the district officer's car and refused to let go "until he pried her hand loose".

Throughout early 1948, AWU members continued to protest the tax, fighting with petitions, press conferences, letters to newspapers, and demonstrations.

[6] In 1947, the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons party (NCNC) sent a delegation to London, England, to protest a proposed Nigerian constitution.

She also caused a stir after writing an article for the Daily Worker that argued colonial rule had "severely marginalized" Nigerian women both politically and economically.

Funmilayo was hit hard by the loss of her husband, having struggled over the past several years with the question of whether to abandon her political work in order to spend more time with him.

[2]: 155–157 Over the next two decades, alongside her political work, Ransome-Kuti began investing time and money to establish new schools throughout Abeokuta – a project that arose from the deep belief in the importance of education and literacy that both she and her husband had shared.

On the African continent, she developed strong ties with Algerian, Egyptian, and Ghanaian women's organisations,[6] and her visits further abroad included trips to England, China, the Soviet Union, Switzerland, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland.

[6]: 151–152 In 1958, when Ransome-Kuti was invited to attend a women's rights conference in the United States, she was denied an American visa because authorities felt "she had too many Communist connections".

[6] Around this time, Ransome-Kuti's political rivals created the National Council of Women's Societies in an attempt to replace the FNWS.

When a 1966 military coup brought a change of power, Ransome-Kuti felt that this was a positive and necessary step forward for the country, but she condemned the violence that followed after the counter-coup that same year.

[2]: 168 In the later years of Anikulapo-Kuti's life, her son Fela, a musician and activist, became known for his vocal criticisms of Nigerian military governments.

[26] Biographer Cheryl Johnson-Odim, notes that Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti's name remains well known throughout Nigeria and that "no other Nigerian woman of her time ranked as such a national figure or had [such] international exposure and connections".

In August of that year, Ransome-Kuti's grandson, musician Seun Kuti, stated to media that he found the proposal "ludicrous to say the least", in light of the government's role in his grandmother's death.

[27] Kuti said that his family had never received an apology for the assault on their compound, with official government statements declaring that Ransome-Kuti had been attacked by "1000 unknown soldiers".

[11][12] It features movie stars like Joke Silva, Kehinde Bankole, Ibrahim Suleiman, Jide Kosoko, and Dele Odule.

It depicts Funmilayo Ransome Kuti's life, beginning with her groundbreaking years as the first female student at Abeokuta Grammar School and continuing through her marriage to Israel Ransome-Kuti.

Together, they confronted injustice by establishing the Abeokuta Women's Union, which led to a violent conflict with traditional and colonial leaders opposed to their pursuit of justice and equality.