Fusor

[2][3] A variant type of fusor had been proposed previously by William Elmore, James L. Tuck, and Ken Watson at the Los Alamos National Laboratory[4] though they never built the machine.

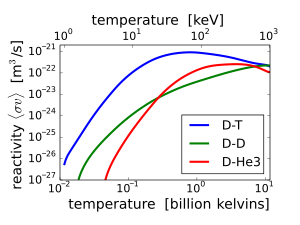

Fusion takes place when nuclei approach to a distance where the nuclear force can pull them together into a single larger nucleus.

In order to produce fusion events, the nuclei must have initial energy great enough to allow them to overcome this Coulomb barrier.

The fusor is part of a broader class of devices that attempts to give the fuel fusion-relevant energies by directly accelerating the ions toward each other.

For comparison, the electron gun in a typical television cathode-ray tube is on the order of 3 to 6 kV, so the complexity of such a device is fairly limited.

The problem with this colliding beam fusion approach, in general, is that the ions will most likely never hit each other no matter how precisely aimed.

Those initially near the cathode will gain much less energy, possibly far too low to undergo fusion with their counterparts on the far side of the central reaction area.

For this reason, the energy needed in a fusor system is higher than one where the fuel is heated by some other method, as some will be "lost" during startup.

[20] Additionally, the scatterings of both the ions, and especially impurities left in the chamber, lead to significant Bremsstrahlung, creating X-rays that carries energy out of the fuel.

[20] This effect grows with particle energy, meaning the problem becomes more pronounced as the system approaches fusion-relevant operating conditions.

In this design, which he called the "multipactor", electrons moving from one electrode to another were stopped in mid-flight with the proper application of a high-frequency magnetic field.

Unfortunately it also led to high erosion on the electrodes when the electrons eventually hit them, and today the multipactor effect is generally considered a problem to be avoided.

Farnsworth reasoned that he could build an electrostatic plasma confinement system in which the "wall" fields of the reactor were electrons or ions being held in place by the multipactor.

Electrostatic pressure from the positively charged electrodes would keep the fuel as a whole off the walls of the chamber, and impacts from new ions would keep the hottest plasma in the center.

In 1965, the board of directors started asking Harold Geneen to sell off the Farnsworth division, but he had his 1966 budget approved with funding until the middle of 1967.

[citation needed] Things changed dramatically with the arrival of Robert Hirsch, and the introduction of the modified Hirsch–Meeks fusor patent.

The observers were startled, but the timing was bad; Hirsch himself had recently revealed the great progress being made by the Soviets using the tokamak.

In response to this surprising development, the AEC decided to concentrate funding on large tokamak projects, and reduce backing for alternative concepts.

From 2006 until his death in 2007, Robert W. Bussard gave talks on a reactor similar in design to the fusor, now called the polywell, that he stated would be capable of useful power generation.

[25] Most recently, the fusor has gained popularity among amateurs, who choose them as home projects due to their relatively low space, money, and power requirements.

In the original fusor design, several small particle accelerators, essentially TV tubes with the ends removed, inject ions at a relatively low voltage into a vacuum chamber.

Whereas 45 megakelvins is a very high temperature by any standard, the corresponding voltage is only 4 kV, a level commonly found in such devices as neon signs and CRT televisions.

Various attempts have been made at increasing deuterium ionization rate, including heaters within "ion-guns", (similar to the "electron gun" which forms the basis for old-style television display tubes), as well as magnetron type devices, (which are the power sources for microwave ovens), which can enhance ion formation using high-voltage electromagnetic fields.

In comparison, any given ion will require a few minutes before undergoing a fusion reaction, so that the monoenergetic picture of the fusor, at least for power production, is not appropriate.

However, the majority of the fusion tends to occur in microchannels formed in areas of minimum electric potential,[30] seen as visible "rays" penetrating the core.

However, in an earlier paper, "A general critique of inertial-electrostatic confinement fusion systems", Rider addresses the common IEC devices directly, including the fusor.

In the case of the fusor the electrons are generally separated from the mass of the fuel isolated near the electrodes, which limits the loss rate.

However, Rider demonstrates that practical fusors operate in a range of modes that either lead to significant electron mixing and losses, or alternately lower power densities.

Typical fusors cannot reach fluxes as high as nuclear reactor or particle accelerator sources, but are sufficient for many uses.

A commercial fusor was developed as a non-core business within DaimlerChrysler Aerospace – Space Infrastructure, Bremen between 1996 and early 2001.