Problem of future contingents

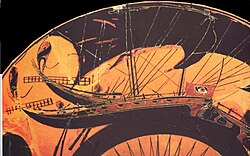

The problem of future contingents seems to have been first discussed by Aristotle in chapter 9 of his On Interpretation (De Interpretatione), using the famous sea-battle example.

[1] Roughly a generation later, Diodorus Cronus from the Megarian school of philosophy stated a version of the problem in his notorious master argument.

Aristotle solved the problem by asserting that the principle of bivalence found its exception in this paradox of the sea battles: in this specific case, what is impossible is that both alternatives can be possible at the same time: either there will be a battle, or there won't.

Aristotle added a third term, contingency, which saves logic while in the same time leaving place for indetermination in reality.

What is necessary is not that there will or that there will not be a battle tomorrow, but the dichotomy itself is necessary: What exactly al-Farabi posited on the question of future contingents is contentious.

Nicholas Rescher argues that al-Farabi's position is that the truth value of future contingents is already distributed in an "indefinite way", whereas Fritz Zimmerman argues that al-Farabi endorsed Aristotle's solution that the truth value of future contingents has not been distributed yet.

[3] Peter Adamson claims they are both correct as al-Farabi endorses both perspectives at different points in his writing, depending on how far he is engaging with the question of divine foreknowledge.

al-Farabi uses the following example; if we argue truly that Zayd will take a trip tomorrow, then he will, but crucially:There is in Zayd the possibility that he stays home....if we grant that Zayd is capable of staying home or of making the trip, then these two antithetical outcomes are equally possible[3]Al-Farabi's argument deals with the dilemma of future contingents by denying that the proposition P "it is true at

[3] Leibniz gave another response to the paradox in §6 of Discourse on Metaphysics: "That God does nothing which is not orderly, and that it is not even possible to conceive of events which are not regular."

What is seen as irregular is only a default of perspective, but does not appear so in relation to universal order, and thus possibility exceeds human logics.

In the early 20th century, the Polish formal logician Jan Łukasiewicz proposed three truth-values: the true, the false and the as-yet-undetermined.

Issues such as this have also been addressed in various temporal logics, where one can assert that "Eventually, either there will be a sea battle tomorrow, or there won't be."