Legitimacy of the State of Israel

As of 2022[update], 28 of the 193 UN member states do not recognize Israeli sovereignty; 25 of the 28 non-recognizing countries are located within the Muslim world, with Cuba, North Korea, and Venezuela representing the remainder.

In the early 1990s, Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian political leader Yasser Arafat exchanged the Letters of Mutual Recognition.

This development aimed to set the stage for negotiations towards a two-state solution (i.e., Israel alongside the State of Palestine), through what would become known as the Oslo Accords, as part of the Israeli–Palestinian peace process.

In 1988 the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the official representative of the Palestinian people, accepted the existence of the State of Israel and advocated for the full implementation of UN Security Council 242.

[20] Significant minorities in Jordan see Israel as an illegitimate state, and reversing the normalization of diplomatic relations was, at least until the late 1990s, central to Jordanian discourse.

This includes 13 members of the Arab League (Algeria, Comoros, Djibouti, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Syria, Tunisia, and Yemen); nine members of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Brunei, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, Mali, Niger, and Pakistan); and Cuba, North Korea, and Venezuela.

[35] Following the 2006 Palestinian legislative election and Hamas' governance of the Gaza Strip, the term "delegitimization" has been frequently applied to rhetoric surrounding the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Professor Emanuel Adler of the University of Toronto says that Israel is willing to accept a situation where its legitimacy may be challenged, because it sees itself as occupying a unique place in the world order.

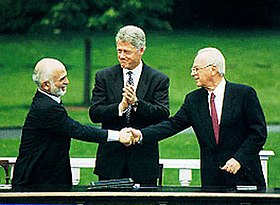

[38] Jordanian linguistics scholar Ibrahim Darwish suggests his own country's language use has changed following the peace treaty signed with Israel on 26 October 1994.

Darwish suggests that before the treaty, Jordanian media employed terms like "Filastiin" (Palestine), "al-ardh al-muhtallah" (the occupied land), and "al-kayaan as-suhyuuni" ("the Zionist entity"), mirroring the state of war and ideological conflict.

[39] Natan Sharansky, head of the Jewish Agency, and Canadian ex-Foreign Minister John Baird have characterized Israel's delegitimization—the third of the Three Ds of antisemitism—as the "new antisemitism".

[40][41] Sharansky and Alan Dershowitz, an American legal scholar, suggest that delegitimization is a double standard used to separate Israel from other legitimate nations.

[44] Israeli philosophy scholar Elhanan Yakira also says portrayal of Israel as "criminal" and denial of Jewish history, specifically the Holocaust, are key to delegitimization.

[45] Dershowitz suggests other standard lines of delegitimization include claims of Israeli colonialism, that its statehood was not granted legally, that it engages in apartheid, and that a one-state solution is necessary to resolve the Israel–Palestine conflict.

"[47] Joel Fishman suggests that "the purpose of delegitimization on the international level is to isolate an intended victim from the community of nations as a prelude to bringing about its downfall and ultimate destruction".

[55][55][56] Elements of pro-Palestinian discourse have also been described as advocating for the destruction of Israel, including slogans, boycotts, proposals for a one-state solution, and calls for the Palestinian right of return.

[70] In 1993, Thomas Friedman, writing in The New York Times, said that a century of delegitimization of the other side had been a barrier to peace for Israelis and Palestinians, and "made sure that the other was never allowed to really feel at home in Israel".