Galactic habitable zone

[1][3] Galactic habitable-zone theory has been criticized due to an inability to accurately quantify the factors making a region of a galaxy favorable for the emergence of life.

[4][5][6] The idea of the circumstellar habitable zone was introduced in 1953 by Hubertus Strughold and Harlow Shapley[7][8] and in 1959 by Su-Shu Huang[9] as the region around a star in which an orbiting planet could retain water at its surface.

[10] In 1981, computer scientist Jim Clarke proposed that the apparent lack of extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way could be explained by Seyfert-type outbursts from an active galactic nucleus, with Earth alone being spared from this radiation by virtue of its location in the galaxy.

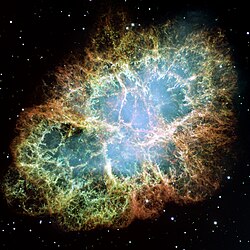

[10] Being too close to the galactic center, however, would expose an otherwise habitable planet to numerous supernovae and other energetic cosmic events, as well as excessive cometary impacts caused by perturbations of the host star's Oort cloud.

These include the distribution of stars and spiral arms, the presence or absence of an active galactic nucleus, the frequency of nearby supernovae that can threaten the existence of life, the metallicity of that location, and other factors.

Various elements, such as iron, magnesium, titanium, carbon, oxygen, silicon, and others, are required to produce habitable planets, and the concentration and ratios of these vary throughout the galaxy.

[13] A 2008 study by Samantha Blair and colleagues attempted to determine the outer edge of the galactic habitable zone by means of analyzing formaldehyde and carbon monoxide emissions from various giant molecular clouds scattered throughout the Milky Way; however, the data is neither conclusive nor complete.

The galactic bulge, for example, experienced an initial wave of extremely rapid star formation,[10] triggering a cascade of supernovae that for five billion years left that area almost completely unable to develop life.

In addition to supernovae, gamma-ray bursts,[18] excessive amounts of radiation, gravitational perturbations[17] and various other events have been proposed to affect the distribution of life within the galaxy.

[20] Considering these factors, the Sun is advantageously placed within the galaxy because, in addition to being outside a spiral arm, it orbits near the corotation circle, maximizing the interval between spiral-arm crossings.

Passing through the dense molecular clouds of galactic spiral arms, stellar winds may be pushed back to the point that a reflective hydrogen layer accumulates in an orbiting planet's atmosphere, perhaps leading to a snowball Earth scenario.

[18] Based on the results of Monte Carlo simulations on a toy model of the Milky Way, the team found that the number of habitable planets is likely to increase with time, though not in a perfectly linear pattern.

[3] In addition, stars "riding" the galaxy's spiral arms may move tens of thousands of light years from their original orbits, thus supporting the notion that there may not be one specific galactic habitable zone.