Gamut

A less common usage defines gamut as the subset of colors contained within an image, scene or video.

There are several algorithms approximating this transformation, but none of them can be truly perfect, since those colors are simply out of the target device's capabilities.

[3] Input devices such as digital cameras or scanners are made to mimic trichromatic human color perception and are based on three sensors elements with different spectral sensitivities, ideally aligned approximately with the spectral sensitivities of human photopsins.

However, most of these devices violate the Luther condition and are not intended to be truly colorimetric, with the exception of tristimulus colorimeters.

The standard observer represents a typical human, but colorblindness leads to a reduced visual gamut.

The axes in these diagrams are the responses of the short-wavelength (S), middle-wavelength (M), and long-wavelength (L) cones in the human eye.

The other letters indicate black (Blk), red (R), green (G), blue (B), cyan (C), magenta (M), yellow (Y), and white colors (W).

The gamut of the CMYK color space is, ideally, approximately the same as that for RGB, with slightly different apexes, depending on both the exact properties of the dyes and the light source.

An object that reflects only a narrow band of wavelengths will have a color close to the edge of the CIE diagram, but it will have a very low luminosity at the same time.

At higher luminosities, the accessible area in the CIE diagram becomes smaller and smaller, up to a single point of white, where all wavelengths are reflected exactly 100 percent; the exact coordinates of white are determined by the color of the light source.

The idea of optimal colors was introduced by the Baltic German chemist Wilhelm Ostwald.

This gamut remains important as a reference for color reproduction,[7] having been updated by newer methods in ISO 12640-3 Annex B.

[8] On modern computers, it is possible to calculate an optimal color solid with great precision in seconds.

Light sources used as primaries in an additive color reproduction system need to be bright, so they are generally not close to monochromatic.

However, as optoelectronic technology matures, single-longitudinal-mode diode lasers are becoming less expensive, and many applications can already profit from this; such as Raman spectroscopy, holography, biomedical research, fluorescence, reprographics, interferometry, semiconductor inspection, remote detection, optical data storage, image recording, spectral analysis, printing, point-to-point free-space communications, and fiber optic communications.

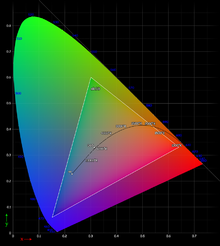

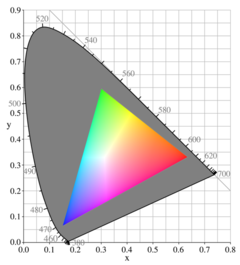

The grayed-out horseshoe shape is the entire range of possible chromaticities , displayed in the CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram format (see below). The colored triangle is the gamut available to the sRGB color space typically used in computer monitors; it does not cover the entire space. The corners of the triangle are the primary colors for this gamut; in the case of a CRT, they depend on the colors of the phosphors of the monitor. At each point, the brightest possible RGB color of that chromaticity is shown, resulting in the bright Mach band stripes corresponding to the edges of the RGB color cube .