Garamond

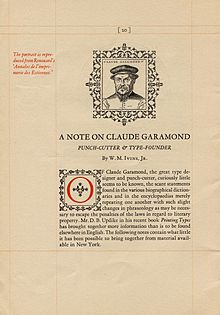

[1] However, although Garamond himself remains considered a major figure in French printing of the sixteenth century, historical research has increasingly placed him in context as one artisan punchcutter among many active at a time of rapid production of new typefaces in sixteenth-century France, and research has only slowly developed into which fonts were cut by him and which by contemporaries; Robert Bringhurst commented that "it was a widespread custom for many years to attribute almost any good sixteenth-century French font" to Garamond.

Lane describes his work as "elegant and executed with consummate skill...to a higher standard than commercial interest demanded";[13] H. D. L. Vervliet wrote that in his later Gros-Canon and Parangonne types (meaning sizes of around 40pt and 18pt respectively) he had achieved "a culmination of Renaissance design.

[27] Historian Beatrice Warde has assessed De Aetna as something of a pilot project, a small book printed to a higher standard than Manutius' norm.

[38][39][40] This form was to appear in many fonts of the period, including Garamond's earlier ones, although by the end of his career he had switched to mostly using an M on the Roman capital model with a serif at top right.

[63][g] If so, his disappearance from history (perhaps due to an early death, since all his presumed work appeared in just four years from 1530 to 1533) and the execution of Augereau on a charge of heresy in 1534 may have allowed Garamond's reputation to develop in the following decade.

[97] According to Lane the most influential Grecs du roi copies were those of Granjon and Haultin, but others may have been cut by Jean Arnould and Nicolas de Villiers, amongst others.

[112] Plantin also commissioned punchcutter Robert Granjon to create alternate characters for three Garamond fonts with shortened ascenders and descenders to allow tighter linespacing.

A proper optical harmony of the angle of slope is characteristic for all Granjon’s Italics; it allowed the compositor to use whole lines of capitals without causing too much giddiness.

"[116][117] Granjon also cut many swash capitals, which Vervliet describes as "deliciously daring" and have often been copied, for instance in Robert Slimbach's revivals for Adobe (discussed below).

[8][123] Jannon wrote in his specimen that: Seeing that for some time many persons have had to do with the art [of printing] who have greatly lowered it ... the desire came upon me to try if I might imitate, after some fashion, some one among those who honourably busied themselves with the art, [men whose deaths] I hear regretted every day [Jannon mentions some eminent printers of the previous century] ... and inasmuch as I could not accomplish this design for lack of types which I needed ... [some typefounders] would not, and others could not furnish me with what I lacked [so] I resolved, about six years ago, to turn my hand in good earnest to the making of punches, matrices and moulds for all sorts of characters, for the accommodation both of the public and of myself.

[125]) Despite the purchase, it is not clear that the office ever much used Jannon's type: historian James Mosley has reported being unable to find books printed by the Imprimerie that use more than two sizes of italic.

[38][130] Opinions of Jannon's engraving quality have varied; Warde found them "so technically brilliant as to be decadent" and "of slight value as a book face" (the surviving Jannon sizes were intended as display faces, cut at 18pt or larger) and Vervliet described them as "famous not so much for the quality of the design but as for the long-term confusion it created", although many reproductions of his work were successful in printing in the twentieth century.

[147] (His younger brother, Simon-Pierre Fournier, rapidly left the family business and became a major exponent of modern ideas in printing, including standardised point sizes and crisp types influenced by contemporary calligraphy.

I shall be happy to display my punches and matrices to all those who are lovers of true beauty ... these are the types that made the reputations of the Estiennes, Plantin and the Elzevirs," and referred to an inventory that he said was in his possession that had been drawn up after Garamond's death in 1561.

Old-style serif typefaces by Garamond and his contemporaries finally fell out of use altogether with the arrival of what is now called the Didone, or modern-face, style of printing in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, promoted by the Didot family in France and others.

Mosley comments:[134] The upheavals of the Revolution coincided with the major shift in the style of printing types that is associated with the family of Didot, and the stock of old materials abruptly lost its value, except as scrap.

No relics of them were saved anywhere, except in commercial centres that had become relative backwaters, like Antwerp, where the Plantin-Moretus printing office piously preserved the collection of its founder ... the term caractères de l'Université became attached by default to the set of apparently early matrices that had survived, its provenance forgotten, in the mixed stock of materials of the national printing-office.Garamond's reputation remained respected, even by members of the Didot family whose type designs came to dominate French printing.

[157][158] These revivals could be made using pantograph machine engraving systems, which gave a cleaner result than historic typefaces whose master punches had been hand-carved, and allowed rapid development of a family in a large range of sizes.

[38][161] A number of historians began in the early twentieth century to question if the Imprimerie nationale Latin-alphabet type was really the work of Garamond, as the Grecs du Roi undoubtedly were.

Doubt was raised by French historian Jean Paillard, but he died during the First World War soon after publishing his conclusions in 1914 and his work remained little-read.

He discussed his concerns with ATF junior librarian Beatrice Warde, who would later move to Europe and become a prominent writer on printing advising the British branch of Monotype.

[129][135][164] In a 1926 paper published on the British typography journal The Fleuron, Beatrice Warde revealed her discovery that the Imprimerie nationale type had been created by Jean Jannon, something she had discovered by examining printing credited to him in London and Paris and through reading the work of Paillard, and perhaps with advice from French bibliographer Marius Audin.

The German company Stempel brought out a crisp revival of the original Garamond typefaces in the 1920s, inspired by a rediscovered specimen from the Egenolff-Berner foundry in Frankfurt, as did Linotype in Britain.

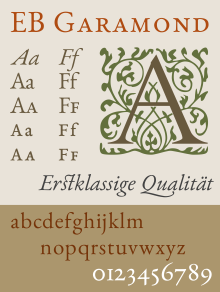

Its lower case 'a' has a sharp and somewhat angular look with a crisp hook at the top left, in contrast to a teardrop design that is common in many other serif typefaces.

Featuring a bold weight, small capitals, optional text figures and automatic ligature insertion, it is particularly popular in the TeX community and is also included on some Linux distributions.

Tschichold stated that Sabon was designed based on the Egenolff-Berner specimen, although there are different accounts on whether it was drawn using the Saint Augusin (around 13pt) or the Parangon (around 18.5pt) models.

They suggested that aspects of Sabon's design may have been copied from a type by Guillaume Le Bé, a large-size specimen of which he had Tschichold reproduced in a textbook.

[255] Monotype's artistic advisor Stanley Morison wrote in his memoir that the italic was based on Granjon's work, but as Carter's commentary on it notes, this seems generally to be a mistake.

[276] One example is Claude Sans, a humanist sans-serif based on the letterforms of Jannon's type, created by Alan Meeks and published by Letraset and later ITC.

Monotype Garamond, the version bundled with Microsoft Office,[249] has a generally smaller design at the same nominal point size compared to Times New Roman and quite spindly strokes, giving it a more elegant but less readable appearance.