Gareth Jones (journalist)

[4] After his third visit to the Soviet Union, he issued a press release under his own name in Berlin on 29 March 1933 describing the widespread famine in detail.

[8] Upon his death, former British prime minister David Lloyd George said, "He had a passion for finding out what was happening in foreign lands wherever there was trouble, and in pursuit of his investigations he shrank from no risk.

[10][11][15][16] The post involved preparing notes and briefings Lloyd George could use in debates, articles, and speeches, and also included some travel abroad.

[18] In late January and some of February 1933, Jones was in Germany covering the accession to power of the Nazi Party, and he was in Leipzig on the day Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor.

Some three weeks later on 23 February in the Richthofen, "the fastest and most powerful three-motored aeroplane in Germany", Jones, along with Sefton Delmer, became the first foreign journalists, after he became Chancellor, to fly with Hitler.

They accompanied Hitler and Joseph Goebbels to Frankfurt where Jones reported for the Western Mail on the new Chancellor's tumultuous acclamation in that city.

[25][5] On his return to Berlin on 29 March, he issued his press release, which was published by many newspapers, including The Manchester Guardian and the New York Evening Post: I walked along through villages and twelve collective farms.

I tramped through the black earth region because that was once the richest farmland in Russia and because the correspondents have been forbidden to go there to see for themselves what is happening.In the train a Communist denied to me that there was a famine.

[26][27]This report was denounced by Moscow-resident British journalist Walter Duranty, who had been obscuring the truth in order to please the Soviet regime.

[5] On 31 March, The New York Times published a denial of Jones's statement by Duranty under the headline "Russians Hungry, But Not Starving".

[28][29][7] Historian Timothy Snyder has written that "Duranty's claim that there was 'no actual starvation' but only 'widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition' echoed Soviet usages and pushed euphemism into mendacity.

This was an Orwellian distinction; and indeed George Orwell himself regarded the Ukrainian famine of 1933 as a central example of a black truth that artists of language had covered with bright colors.

"[30] In Duranty's article, Kremlin sources denied the existence of a famine; part of The New York Times headline was: "Russian and Foreign Observers in Country See No Ground for Predictions of Disaster.

The prophecy of Paul Scheffer in 1929–30 that collectivisation of agriculture would be the nemesis of Communism has come absolutely true.On 13 May, The New York Times published a strong rebuttal of Duranty by Jones, who stood by his report: My first evidence was gathered from foreign observers.

After his Ukraine articles, the only work Jones could get was in Cardiff on the Western Mail covering "arts, crafts and coracles", according to his great-nephew Nigel Linsan Colley.

[33] Yet he managed to get an interview with the owner of nearby St Donat's Castle, the American press magnate William Randolph Hearst.

Hearst published Jones's account of what had happened in Ukraine – as he did for the almost identical eye-witness testimony of the disillusioned American Communist Fred Beal.

[33][36] Banned from the Soviet Union, Jones turned his attention to the Far East and in late 1934 he left Britain on a "Round-the-World Fact-Finding Tour".

[8] Jones and Müller were captured en route by bandits who demanded a ransom of 200 Mauser firearms and 100,000 Chinese dollars (according to The Times, equivalent to about £8,000).

[43] On 17 August 1935, The Times reported that the Chinese authorities had found Jones's body the previous day with three bullet wounds.

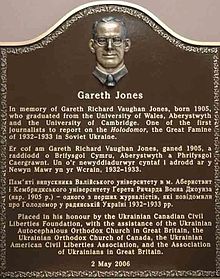

[9]On 2 May 2006, a trilingual (English/Welsh/Ukrainian) plaque was unveiled in Jones's memory in the Old College at Aberystwyth University, in the presence of his niece Margaret Siriol Colley, and the Ukrainian Ambassador to the UK, Ihor Kharchenko, who described him as an "unsung hero of Ukraine".

[47] In November 2009, Jones's diaries recording the Great Soviet Famine of 1932–33, which he described as man-made, went on display for the first time in the Wren Library of Trinity College, Cambridge.

[50][51][52] In 2012, the documentary film Hitler, Stalin, and Mr Jones, directed by George Carey, was broadcast on the BBC series Storyville.