Diving rebreather

The purpose is to extend the breathing endurance of a limited gas supply, and, for covert military use by frogmen or observation of underwater life, to eliminate the bubbles produced by an open circuit system.

Fault tolerant design can make a rebreather less likely to fail in a way that immediately endangers the user, and reduces the task loading on the diver which in turn may lower the risk of operator error.

[13] Operational scope and restrictions of SCRs: Closed circuit diving rebreathers may be manually or electronically controlled, and use both pure oxygen and a breathable mixed gas diluent.

This class of rebreather diving provides an opportunity to sell training and certification which omits a large part of the more complex and difficult skills, and reduces the amount of equipment that the diver needs to carry.

Although there are several design variations of diving rebreather, all types have a gas-tight reservoir to contain the breathing gas at ambient pressure that the diver inhales from and exhales into.

The pendulum system is structurally simpler, but inherently contains a larger dead space of unscrubbed gas in the combined exhalation and inhalation tube, which is rebreathed.

Military and recreational divers use these because they provide better underwater duration than open circuit, have a deeper maximum operating depth than oxygen rebreathers and can be fairly simple and cheap.

Passive addition rebreathers with small discharge ratios may become hypoxic near the surface when moderate or low oxygen fraction supply gas is used, making it necessary to switch gases between deep and shallow diving.

This approach is based on the assumption that the volumetric breathing rate of a diver is directly proportional to metabolic oxygen consumption, which experimental evidence indicates is close enough to work.

[31] Closed circuit rebreathers supply two breathing gases to the loop: one is pure oxygen and the other is a diluent or diluting gas such as air, nitrox, heliox or trimix.

This set point is chosen to provide an acceptable risk of both long-term and acute oxygen toxicity, while minimizing the decompression requirements for the planned dive profile.

The helium helmet uses the same breastplate as a standard Mark V except that the locking mechanism is relocated to the front, there is no spitcock, there is an additional electrical connection for heated underwear, and on later versions a two or three-stage exhaust valve was fitted to reduce the risk of flooding the scrubber.

Flow rate of the injector nozzle was nominally 0.5 cubic foot per minute at 100 psi above ambient pressure, which would blow 11 times the volume of the injected gas through the scrubber.

Mouthpiece retaining straps have been shown in navy experience over several years to be effective at protecting the airway in an unconscious rebreather diver as an alternative to a full-face mask.

This effect can be reduced by insulating the canister walls where they are in contact with absorbent material[47] During ascent the gas in the breathing circuit will expand, and must have some way of escape before the pressure difference causes injury to the diver or damage to the loop.

The overpressure valve is typically mounted on the counterlung and in military diving rebreathers it may be fitted with a diffuser, which helps to conceal the diver's presence by masking the release of bubbles, by breaking them up to sizes which are less easily detected.

[55] The fundamental requirements for the control of the gas mixture in the breathing circuit for any rebreather application are that the carbon dioxide is removed, and kept at a tolerable level, and that the partial pressure of oxygen is kept within safe limits.

[16] Instrumentation may vary from the minimal depth, time and remaining gas pressure necessary for a closed circuit oxygen rebreather or semi-closed nitrox rebreather to redundant electronic controllers with multiple oxygen sensors, redundant integrated decompression computers, carbon dioxide monitoring sensors and a head-up display of warning and alarm lights with a sound and vibration alarm.

Work of breathing is another issue that has room for improvement, and is a severe limitation on acceptable maximum depth of operation, as the circulation of gas through the scrubber is almost always powered by the lungs of the diver.

Continued use of a rebreather with an ineffective scrubber is not possible for very long, as the levels will become toxic and the user will experience extreme respiratory distress, followed by loss of consciousness and death.

The mixture is generally a liquid or watery slurry with a chalky and bitter taste, which should prompt the diver to switch to an alternative source of breathing gas and immediately rinse their mouth out well with water.

The methods available for monitoring the condition of the scrubber and predicting and identifying imminent breakthrough include: Fault tolerance is the property that enables a system to continue operating properly in the event of the failure of some of its components.

Monitoring the gas composition in the breathing loop can only be done by electrical sensors, bringing the underwater reliability of the electronic sensing system into the safety critical component category.

Fault tolerant design can make a rebreather less likely to fail in a way that immediately endangers the user, and reduces the task loading on the diver which in turn may lower the risk of operator error.

It has been shown that the reliability of this system is lower than originally expected due to a lack of sufficient statistical independence of the three sensors, and that outcomes are not symmetrical – the effects of faulty low or high partial pressure readings are also depth dependent.

[65] Some rebreather manufacturers have developed linear temperature probes which identify the position of the reactive front, allowing the user to estimate the remaining duration of the canister.

Measuring gas in the mouthpiece has problems due to dead space, and mounting in the inhalation hose near the mouthpiece makes the sensor sensitive to small leaks in the inhalation check valve, while also able to detect high CO2 due to major check valve leaks which would cause a big increase in dead space, which would not be detected if the sensor is further upstream in the loop.

A better option would be to measure both inhaled and exhaled CO2 levels, and this would require sensors that are fast and reliable in wet conditions, and reasonably inexpensive[65] Following the strong endorsement by Rebreather Forum 3 of the use of written checklists to improve safety, Cis-Lunar Development Laboratories programmed an electronic pre-dive checklist into their MK-5P rebreather operating system, as a way to prevent the user from neglecting to carry out the recommended checks before use.

This was considered successful and implemented on later generations in the Poseidon MK-VI and SE7EN rebreathers, and developed to include robust internal diagnostics for the core electronic components and software, and automatic calibration of the oxygen sensor cells at normobaric pressures.

The intrinsically higher risk of mechanical failure due to high complexity can be compensated by engineering redundancy, both of the control system and bailout gas supply, and appropriate training.

- 1 Dive/surface valve with loop non-return valves

- 2 Exhalation hose

- 3 Counterlung fore-chamber

- 4 Non-return valve to discharge bellows

- 5 Discharge bellows

- 6 Overpressure valve

- 7 Main counterlung bellows

- 8 Addition valve

- 9 Scrubber (axial flow)

- 10 Inhalation hose

- 11 Breathing gas storage cylinder

- 12 Cylinder valve

- 13 Regulator first stage

- 14 Submersible pressure gauge

- 15 Bailout demand valve

- 1 Dive/surface valve with loop non-return valves

- 2 Exhaust hose

- 3 Scrubber canister (axial flow)

- 4 Counterlung

- 5 Loop overpressure valve

- 6 Inhalation valve

- 7 Breathing gas supply cylinder

- 8 Cylinder valve

- 9 Absolute pressure regulator

- 10 Submersible pressure gauge

- 11 Automatic Diluent Valve

- 12 Constant Mass Flow metering orifice

- 13 Manual bypass valve

- 14 Bailout demand valve

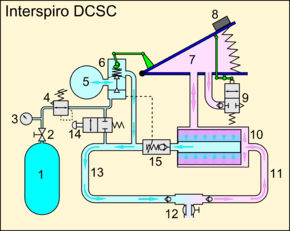

- 1 Nitrox feed gas cylinder

- 2 Cylinder valve

- 3 Pressure gauge

- 4 Feed gas first stage regulator

- 5 Dosage chamber

- 6 Dosage mechanism with control linkage from bellows cover

- 7 Hinged bellows counterlung

- 8 Bellows weight

- 9 Exhaust valve with control linkage from bellows cover

- 10 Radial flow scrubber

- 11 Exhalation hose

- 12 Mouthpiece with dive/surface valve and loop non-return valves

- 13 Inhalation hose

- 14 Manual bypass valve

- 15 Low gas warning valve

- 1 Dive/surface valve

- 2 Two way breathing hose

- 3 Scrubber (radial flow)

- 4 Counterlung

- 5 Automatic make-up valve

- 6 Manual bypass valve

- 7 Breathing gas storage cylinder

- 8 Cylinder valve

- 9 Regulator first stage

- 10 Submersible pressure gauge

- 11 Overpressure valve

- 1 Dive/surface valve with loop non return valves

- 2 Exhaust hose

- 3 Scrubber (axial flow)

- 4 Counterlung

- 5 Overpressure valve

- 6 Inhalation hose

- 7 Breathing gas storage cylinder

- 8 Cylinder valve

- 9 Regulator first stage

- 10 Submersible pressure gauge

- 11 Automatic make-up valve

- 12 Manual bypass valve

- 1 Dive/surface valve and loop non-return valves

- 2 Exhaust hose

- 3 Scrubber (axial flow)

- 4 Counterlung

- 5 Overpressure valve

- 6 Inhalation valve

- 7 Oxygen cylinder

- 8 Oxygen cylinder valve

- 9 Absolute pressure oxygen regulator

- 10 Oxygen submersible pressure gauge

- 11 Oxygen manual bypass valve

- 12 Oxygen constant mass flow metering orifice

- 13 Electronically controlled solenoid operated oxygen injection valve

- 14 Diluent cylinder

- 15 Diluent cylinder valve

- 16 Diluent regulator

- 17 Diluent submersible pressure gauge

- 18 Bailout demand valve

- 19 Manual diluent bypass valve

- 20 Automatic diluent valve

- 21 Oxygen sensor cells

- 22 Electronic control and monitoring circuits

- 23 Primary and secondary display units