Gastornis

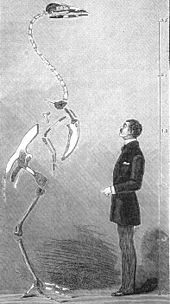

Gastornis is an extinct genus of large, flightless birds that lived during the mid-Paleocene to mid-Eocene epochs of the Paleogene period.

Gastornis species were very large birds that were traditionally thought to have been predators of various smaller mammals, such as ancient, diminutive equids.

However, several lines of evidence, including the lack of hooked claws (in known Gastornis footprints), studies of their beak structure and isotopic signatures of their bones, have caused scientists to now consider that these birds were probably herbivorous, feeding on tough plant material and seeds.

It was named after Gaston Planté, described as a "studious young man full of zeal", who had discovered the first fossils in clay (Argile Plastique [fr]) formation deposits at Meudon, near Paris.

The skulls of these original Gastornis fossils were unknown, other than nondescript fragments and several bones used in Lemoine's illustration, which turned out to be those of other animals.

Cope considered the fossils to be of a distinct genus and species of giant ground bird; in 1876, he named the remains Diatryma gigantea (/ˌdaɪ.əˈtraɪmə/ DY-ə-TRY-mə),[6] from the Ancient Greek διάτρημα (diatrema), meaning "through a hole", in reference to the large foramina (perforations) that penetrated some of the foot bones.

[7][8] In 1894, a single gastornithid toe bone from New Jersey was described by Cope's "rival" Othniel Charles Marsh, and classified as a new genus and species: Barornis regens.

[9] In 1916, an American Museum of Natural History expedition to the Bighorn Basin (Willwood Formation, Wyoming) found the first nearly-complete skull and skeleton, which was described in 1917 and gave scientists their first clear picture of the bird.

[10] Further meaningful comparisons between Gastornis and Diatryma were made more difficult by Lemoine's incorrect skeletal illustration, the composite nature of which was not discovered until the early 1980s.

Following this, several authors began to recognize a greater degree of similarity between the European and North American birds, often placing both in the same order (†Gastornithiformes) or even family (†Gastornithidae).

This newly-realized degree of similarity caused many scientists to, tentatively, accept the animals' synonymy pending a comprehensive review of the anatomy of both genera, in which Gastornis has the taxonomic priority.

[11][12] Gastornis is known from a large amount of fossil remains, but the clearest picture of the bird comes from a few nearly complete specimens of the species G. giganteus.

Beginning in the late 1980s with the first phylogenetic analysis of gastornithid relationships, consensus began to grow that they were close relatives of the lineage that includes waterfowl and screamers, the Anseriformes.

Additional European species of Gastornis are G. russelli (Martin, 1992) from the late Paleocene of Berru, France, and G. sarasini (Schaub, 1929) from the early-middle Eocene.

The holotype (MHNT.PAL.2018.20.1) is a nearly complete mandible which differs from other species within the genus, and the paratypes consist of the maxilla, right quadrate, femur shaft, tibiotarsus (two left and one right) and six cervical vertebrae.

[26] Specimen YPM PU 13258 from lower Eocene Willwood Formation rocks of Park County, Wyoming also seems to be a juvenile – perhaps also of G. giganteus, in which case it would be an even younger individual.

[32] Footprints attributed to gastornithids (possibly a species of Gastornis itself), described in 2012, showed that these birds lacked strongly hooked talons on the hind legs, another line of evidence suggesting that they did not have a predatory lifestyle.

[14] Studies of the calcium isotopes in the bones of specimens of Gastornis by Thomas Tutken and colleagues showed no evidence that it had meat in its diet.

While no direct association exists between Ornitholithus and Gastornis fossils, no other birds of sufficient size are known from that time and place; while the large Diogenornis and Eremopezus are known from the Eocene, the former lived in South America (still separated from North America by the Tethys Ocean then) and the latter is only known from the Late Eocene of North Africa, which also was separated by an (albeit less wide) stretch of the Tethys Ocean from Europe.

This would nicely match the remains of eggs a bit smaller than those of the living ostrich, which have also been found in Paleogene deposits of Provence, were it not for the fact that these eggshell fossils also date from the Eocene, but no Remiornis bones are yet known from that time.

They were discussed by Charles Lyell in his Elements of Geology as an example of the incompleteness of the fossil record – no bones had been found associated with the footprints.

They were brought to the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle when Desnoyers started to work there, and the last documented record of them deals with their presence in the geology exhibition of the MNHN in 1912.

Although these birds have long been considered to be predators or scavengers, the absence of raptor-like claws supports earlier suggestions that they were herbivores.

This has been based in part on some fibrous strands recovered from a Green River Formation deposit at Roan Creek, Colorado, which were initially believed to represent Gastornis feathers and named Diatryma?

[52] All other fossil remains are from the Eocene, though it is currently unknown how the genus Gastornis dispersed out of Europe and into other continents, and whether such assertion is even true given the potential validity of Diatryma.

[12] Given the possible presence of Gastornis fossils in the early Eocene of western China, these birds may have spread east from Europe and crossed into North America via the Bering land bridge.

Gastornis also may have spread both east and west, arriving separately in eastern Asia and in North America across the Turgai Strait.

[52] European Gastornis survived somewhat longer than their North American counterparts, which seems to coincide with a period of increased isolation of the continent.