Gastric dilatation volvulus

The word bloat is often used as a general term to mean gas distension without stomach torsion (a normal change after eating), or to refer to GDV.

Other possible symptoms include firm distension of the abdomen, weakness, depression, difficulty breathing, hypersalivation, and retching without producing any vomitus (nonproductive vomiting).

Haemological conditions that may be identified include: neutrophilic leukocytosis, lymphopaenia, leukopaenia, thrombocytopaenia, and haemoconcentration.

[1] Gastric dilatation volvulus is multifactorial without any one cause being identified, but in all cases the immediate prerequisite is a dysfunction of the sphincter between the esophagus and stomach and an obstruction of outflow through the pylorus.

If there is a family history of the condition the risk is even more severe, highlighting a heritability to the predisposing factors.

[11] The breeds most likely to develop GDV are the Great Dane (10 times more likely), Weimaraner (4.6) St Bernard (4.2) and the Irish Setter (3.5).

[1] One study has found certain alleles of the DLA88, DRB1 and TLR5 genes, which are part of the canine immune system, to predispose a dog to GDV.

[13] Further studies have associated these alleles with greater diversity in the gut microbiome and an increased risk of GDV.

[1] One common recommendation in the past has been to raise the food bowl of dogs when they eat, but this was shown to increase the risk in one study.

If the volvulus is greater than 180°, the esophagus is closed off, thereby preventing the animal from relieving the condition by belching or vomiting.

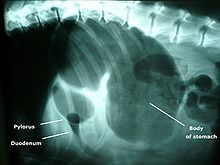

The breed and history often gives a significant suspicion of the condition, and a physical examination often reveals the telltale sign of a distended abdomen with abdominal tympany.

Antiarrhythmic drugs should be administered after starting fluid therapy to stabilise blood pressure.

Gastropexy involves suturing the pyloric antrum to the abdominal wall to prevent recurrence of GDV.

[1] Recurrence of GDV attacks can be a problem, occurring in up to 80% of dogs treated medically only (without surgery).

[21] To prevent recurrence, at the same time the bloat is treated surgically, a right-side gastropexy is often performed, which by a variety of methods firmly attaches the stomach wall to the body wall, to prevent it from twisting inside the abdominal cavity in the future.

While dogs that have had gastropexies still may develop gas distension of the stomach, a significant reduction in recurrence of gastric volvulus is seen.

A delay in treatment greater than 6 hours or the presence of peritonitis, sepsis, hypotension, or disseminated intravascular coagulation are negative prognostic indicators.

[26] With prompt treatment and good preoperative stabilization of the patient, mortality is significantly lessened to 10% overall (in a referral setting).

A longer time from presentation to surgery was associated with a lower mortality, presumably because these dogs had received more complete preoperative fluid resuscitation, thus were better cardiovascularly stabilized prior to the procedure.

[12] In fact, the lifetime risk for a Great Dane to develop GDV has been estimated to be close to 37%.