Gauss's law

In its integral form, it states that the flux of the electric field out of an arbitrary closed surface is proportional to the electric charge enclosed by the surface, irrespective of how that charge is distributed.

Where no such symmetry exists, Gauss's law can be used in its differential form, which states that the divergence of the electric field is proportional to the local density of charge.

The law was first[1] formulated by Joseph-Louis Lagrange in 1773,[2] followed by Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1835,[3] both in the context of the attraction of ellipsoids.

It is one of Maxwell's equations, which forms the basis of classical electrodynamics.

The law can be expressed mathematically using vector calculus in integral form and differential form; both are equivalent since they are related by the divergence theorem, also called Gauss's theorem.

In a curved spacetime, the flux of an electromagnetic field through a closed surface is expressed as where

is an orthonormal element of the two-dimensional surface surrounding the charge

The electric field is then calculated as the potential's negative gradient.

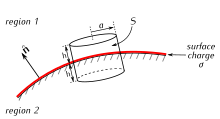

Gauss's law makes it possible to find the distribution of electric charge: The charge in any given region of the conductor can be deduced by integrating the electric field to find the flux through a small box whose sides are perpendicular to the conductor's surface and by noting that the electric field is perpendicular to the surface, and zero inside the conductor.

An exception is if there is some symmetry in the problem, which mandates that the electric field passes through the surface in a uniform way.

See the article Gaussian surface for examples where these symmetries are exploited to compute electric fields.

By the divergence theorem, Gauss's law can alternatively be written in the differential form:

The integral and differential forms are mathematically equivalent, by the divergence theorem.

The integral form of Gauss's law is: for any closed surface S containing charge Q.

In contrast, "bound charge" arises only in the context of dielectric (polarizable) materials.

When such materials are placed in an external electric field, the electrons remain bound to their respective atoms, but shift a microscopic distance in response to the field, so that they're more on one side of the atom than the other.

This formulation of Gauss's law states the total charge form:

where ΦD is the D-field flux through a surface S which encloses a volume V, and Qfree is the free charge contained in V. The flux ΦD is defined analogously to the flux ΦE of the electric field E through S: The differential form of Gauss's law, involving free charge only, states:

In homogeneous, isotropic, nondispersive, linear materials, there is a simple relationship between E and D:

For the case of vacuum (aka free space), ε = ε0.

The superposition principle states that the resulting field is the vector sum of fields generated by each particle (or the integral, if the charges are distributed smoothly in space).

Coulomb's law states that the electric field due to a stationary point charge is:

If we take the divergence of both sides of this equation with respect to r, and use the known theorem[9]

Using the "sifting property" of the Dirac delta function, we arrive at

Since Coulomb's law only applies to stationary charges, there is no reason to expect Gauss's law to hold for moving charges based on this derivation alone.

be the electric field created inside and outside the sphere respectively.

The RHS is the electric flux generated by a charged sphere, and so:

However, Coulomb's law can be proven from Gauss's law if it is assumed, in addition, that the electric field from a point charge is spherically symmetric (this assumption, like Coulomb's law itself, is exactly true if the charge is stationary, and approximately true if the charge is in motion).

Taking S in the integral form of Gauss's law to be a spherical surface of radius r, centered at the point charge Q, we have

By the assumption of spherical symmetry, the integrand is a constant which can be taken out of the integral.