Gazetteer

[4][5] It typically contains information concerning the geographical makeup, social statistics and physical features of a country, region, or continent.

Content of a gazetteer can include a subject's location, dimensions of peaks and waterways, population, gross domestic product and literacy rate.

[6] It includes as an example a work by the British historian Laurence Echard (d. 1730) in 1693 that bore the title "The Gazetteer's: or Newsman's Interpreter: Being a Geographical Index".

Thematic gazetteers list places or geographical features by theme; for example fishing ports, nuclear power stations, or historic buildings.

Gazetteer editors gather facts and other information from official government reports, the census, chambers of commerce, together with numerous other sources, and organise these in digest form.

[11] Historian Truesdell S. Brown asserts that what Dionysius describes in this quote about the logographers should be categorized not as a true "history" but rather as a gazetteer.

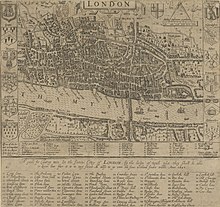

[16] The Speculum Britanniae (1596) of the Tudor era English cartographer and topographer John Norden (1548–1625) had an alphabetical list of places throughout England with headings showing their administrative hundreds and referenced to attached maps.

[18] Starting in 1662, the Hearth Tax Returns with attached maps of local areas were compiled by individual parishes throughout England while a duplicate of their records were sent to the central government offices of the Exchequer.

The Italian monk Phillippus Ferrarius (d. 1626) published his geographical dictionary "Epitome Geographicus in Quattuor Libros Divisum" in the Swiss city of Zürich in 1605.

[19] With the gradual expansion of Laurence Echard's (d. 1730) gazetteer of 1693, it too became a universal geographical dictionary that was translated into Spanish in 1750, into French in 1809, and into Italian in 1810.

[25] The reviewer of Joseph Scott's 1795 gazetteer commented that it was "little more than medleys of politics, history and miscellaneous remarks on the manners, languages and arts of different nations, arranged in the order in which the territories stand on the map".

[26] Gazetteers became widely popular in Britain in the 19th century, with publishers such as Fullarton, Mackenzie, Chambers and W & A. K. Johnston, many of whom were Scottish, meeting public demand for information on an expanding Empire.

[28] In Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD) China, the Yuejue Shu (越絕書) written in 52 AD is considered by modern sinologists and historians to be the prototype of the gazetteer (Chinese: difangzhi), as it contained essays on a wide variety of subjects including changes in territorial division, the founding of cities, local products, and customs.

[33][36] Song gazetteers also made lists and descriptions of city walls, gate names, wards and markets, districts, population size, and residences of former prefects.

[37] In 610 after the Sui dynasty (581–618) united a politically divided China, Emperor Yang of Sui had all the empire's commanderies prepare gazetteers called 'maps and treatises' (Chinese: tujing) so that a vast amount of updated textual and visual information on local roads, rivers, canals, and landmarks could be utilized by the central government to maintain control and provide better security.

[43] Emperor Taizu of Song ordered Lu Duosun and a team of cartographers and scholars in 971 to initiate the compilation of a huge atlas and nationwide gazetteer that covered the whole of China proper,[39] which comprised approximately 1,200 counties and 300 prefectures.

[49] Even within China, ethnographic information on ethnic minorities of non-Han peoples were often described in the local histories and gazetteers of provinces such as Guizhou during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

[52] Historian Timothy Brook states that Ming dynasty gazetteers demonstrate a shift in the attitudes of Chinese gentry towards the traditionally lower merchant class.

[53] Hence, the gentry figures composing the gazetteers in the latter half of the Ming period spoke favorably of merchants, whereas before they were rarely mentioned.

The Christian missionary William Muirhead (1822–1900), who lived in Shanghai during the late Qing period, published the gazetteer "Dili quanzhi", which was reprinted in Japan in 1859.

[62] The printing of gazetteers was revived in 1956 under Mao Zedong and again in the 1980s, after the reforms of the Deng era to replace the people's communes with traditional townships.

[66] Like Chinese gazetteers, there were national, provincial, and local prefecture Korean gazetteers which featured geographic information, demographic data, locations of bridges, schools, temples, tombs, fortresses, pavilions, and other landmarks, cultural customs, local products, resident clan names, and short biographies on well-known people.

[67][68][69] In an example of the latter, the 1530 edition of "Sinjŭng Tongguk yŏji sŭngnam" ('Revised Augmented Survey of the Geography of Korea') gave a brief statement about Pak Yŏn (1378–1458), noting his successful career in the civil service, his exceptional filiality, his brilliance in music theory, and his praisable efforts in systematizing ritual music for Sejong's court.

[67] King Sejong established the Joseon dynasty's first national gazetteer in 1432, called the "Sinch'an p'aldo" ('Newly Compiled Geographic Treatise on the Eight Circuits').

[77] B. S. Baliga writes that the history of the gazetteer in Tamil Nadu can be traced back to the classical corpus of Sangam literature, dated 200 BC to 300 AD.

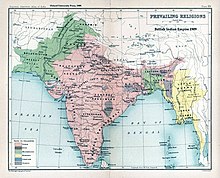

[78] Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, the vizier to Akbar the Great of the Mughal Empire, wrote the Ain-e-Akbari, which included a gazetteer with valuable information on India's population in the 16th century.