Gemistos Plethon

[6] As revealed in his last literary work, the Nomoi or Book of Laws, which he circulated only among close friends, he rejected Christianity in favour of a return to the worship of the classical Hellenic gods, mixed with ancient wisdom based on Zoroaster and the Magi.

[14] Some time before 1410, Emperor Manuel II Paleologos sent him to Mystra in the Despotate of Morea in the southern Peloponnese,[15] which remained his home for the rest of his life.

[16] In 1428 Plethon was consulted by Emperor John VIII on the issue of unifying the Greek and Latin churches, and advised that both delegations should have equal voting power.

Marsilio Ficino's introduction to the translation of Plotinus[19] has traditionally been interpreted to the effect that Cosimo de' Medici attended Pletho's lectures and was inspired to found the Accademia Platonica in Florence, where Italian students of Plethon continued to teach after the conclusion of the council.

In fact, communication between Plethon and Cosimo de' Medici - for whose meeting there is no independent evidence - would have been severely constrained by the language barrier.

[11] While still in Florence, Pletho wrote a volume titled Wherein Aristotle disagrees with Plato, commonly called De Differentiis, to correct the misunderstandings he had encountered.

In 1466, some of his Italian disciples, headed by Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, stole his remains from Mistra and interred them in the Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini, "so that the great Teacher may be among free men".

[citation needed] Believing that the Peloponnesians were direct descendants of the ancient Hellenes, Plethon rejected Justinian's idea of a universal Empire in favour of recreating the Hellenistic civilization, the zenith of Greek influence.

[21] In his 1415 and 1418 pamphlets he urged Manuel II and his son Theodore Palaiologos to turn the peninsula into a cultural island with a new constitution of strongly centralised monarchy advised by a small body of middle-class educated men.

Morea was under invasion from Sultan Mehmet II, and Theodora escaped with Demetrios to Constantinople where she gave the manuscript back to Gennadius, reluctant to destroy the only copy of such a distinguished scholar's work herself.

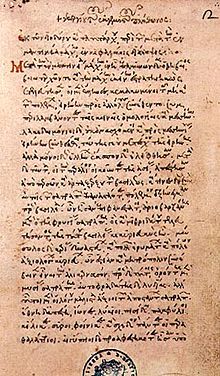

Gennadius burned it in 1460; however, in a letter to the Exarch Joseph (which still survives) he details the book, providing chapter headings and brief summaries of the contents.

He rejected the concept of a brief reign of evil followed by perpetual happiness, and held that the human soul is reincarnated, directed by the gods into successive bodies to fulfill divine order.

This same divine order, he believed, governed the organisation of bees, the foresight of ants and the dexterity of spiders, as well as the growth of plants, magnetic attraction, and the amalgamation of mercury and gold.

[11] Plethon drew up plans in his Nómoi to radically change the structure and philosophy of the Byzantine Empire in line with his interpretation of Platonism.

The new state religion was to be founded on a hierarchical pantheon of pagan gods, based largely upon the ideas of humanism prevalent at the time, incorporating themes such as rationalism and logic.

Of these Hera is third in command after Poseidon, creatress and ruler of indestructible matter, and the mother by Zeus of the heavenly gods, demi-gods and spirits.

Early in his writing career, E. M. Forster attempted a historical novel about Plethon and Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, but was not satisfied with the result and never published it — though he kept the manuscript and later showed it to Naomi Mitchison.

Pound was fascinated by the effect that Plethon's conversation may have had on Cosimo de Medici and his decision to acquire Greek manuscripts of Plato and Neoplatonic philosophers.

By having manuscripts brought from Greece and becoming the patron of "the young boy, Ficino," Cosimo facilitated the preservation and transmission of the Greek cultural patrimony into the modern world after the fall of Constantinople in 1453.