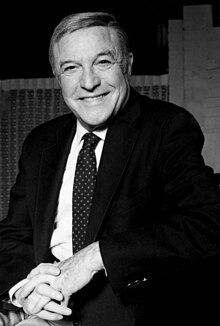

Gene Kelly

[10] According to dance and art historian Beth Genné, working with his co-director Donen in Singin' in the Rain and in films with director Vincente Minnelli, "Kelly ... fundamentally affected the way movies are made and the way we look at them.

He entered the Pennsylvania State College as a journalism major, but after the 1929 crash he left school and found work in order to help his family financially.

His first Broadway assignment, in November 1938, was as a dancer in Cole Porter's Leave It to Me!—as the American ambassador's secretary who supports Mary Martin while she sings "My Heart Belongs to Daddy".

In 1939, he was selected for a musical revue, One for the Money, produced by the actress Katharine Cornell, who was known for finding and hiring talented young actors.

5 (1943) and in Christmas Holiday (1944), he took the male lead in Cole Porter's Du Barry Was a Lady (1943) with Lucille Ball, in a part originally intended for Ann Sothern.

Despite this, critic Manny Farber was moved to praise Kelly's "attitude", "clarity", and "feeling" as an actor while inauspiciously concluding, "The two things he does least well—singing and dancing—are what he is given most consistently to do.

In Ziegfeld Follies (1946)—which was produced in 1944 but delayed for release—Kelly collaborated with Fred Astaire, for whom he had the greatest admiration, in "The Babbitt and the Bromide" challenge dance routine.

He was stationed in the Photographic Section, Washington, D.C., where he helped write and direct a range of documentaries – this stimulated his interest in the production side of filmmaking.

The film was considered so weak that the studio asked Kelly to design and insert a series of dance routines; they noticed his ability to carry out such assignments.

In the interim, he capitalized on his swashbuckling image as d'Artagnan in The Three Musketeers in 1948—and appeared with Vera-Ellen in the Slaughter on Tenth Avenue ballet in Words and Music (1948 again).

[31] In 1949 he starred in Take Me Out to the Ball Game, his second film with Sinatra, where Kelly paid tribute to his Irish heritage in "The Hat My Father Wore on St. Patrick's Day" routine.

I needed one to watch my performance, and one to work with the cameraman on the timing ... without such people as Stanley, Carol Haney, and Jeanne Coyne I could never have done these things.

This exposé of organized crime is set in New York's "Little Italy" during the late 19th century and focuses on the Black Hand, a group that extorts money upon threat of death.

In his book Easy the Hard Way, Joe Pasternak, head of another of MGM's musical units, singled out Kelly for his patience and willingness to spend as much time as necessary to enable the ailing Garland to complete her part.

MGM had lost faith in Kelly's box-office appeal, and as a result It's Always Fair Weather premiered at 17 drive-in theaters around the Los Angeles metroplex.

Next followed Kelly's last musical film for MGM, Les Girls (1957), in which he joined Mitzi Gaynor, Kay Kendall, and Taina Elg.

The third picture he completed was a co-production between MGM and himself, a B-film, The Happy Road (1957), set in his beloved France, his first foray in a new role as producer-director-actor.

[33] Early in 1960, Kelly, an ardent Francophile and fluent French speaker, was invited by A. M. Julien, the general administrator of the Paris Opéra and Opéra-Comique,[13] to select his own material and create a modern ballet for the company, the first time an American had received such an assignment.

[35] The special focuses on Gene Kelly in a musical tour around Manhattan, dancing along such landmarks as Rockefeller Center, the Plaza Hotel, and the Museum of Modern Art, which serve as backdrops for the show's entertaining production numbers.

[16] He directed veteran actors James Stewart and Henry Fonda in the comedy Western The Cheyenne Social Club (1970), which performed poorly at the box office.

Kelly was a guest on the 1975 television special starring Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gormé, "Our Love Is Here to Stay," appearing with his son, Tim, and daughter, Bridget.

His final film role was in Xanadu (1980), a flop despite a popular soundtrack that spawned five Top 20 hits by the Electric Light Orchestra, Cliff Richard, and Kelly's co-star Olivia Newton-John.

When he began his collaborative film work, he was influenced by Robert Alton and John Murray Anderson, striving to create moods and character insight with his dances.

[10] A clear progression was evident in his development, from an early concentration on tap and musical comedy style to greater complexity using ballet and modern dance forms.

Biographer Clive Hirschhorn writes: "As a child, he used to run for miles through parks and streets and woods—anywhere, just as long as he could feel the wind against his body and through his hair.

[38] Kelly's reasoning behind this was that he felt the kinetic force of live dance often evaporated when brought to film, and he sought to partially overcome this by involving the camera in movement and giving the dancer a greater number of directions in which to move.

Examples of this abound in Kelly's work and are well illustrated in the "Prehistoric Man" sequence from On the Town and "The Hat My Father Wore on St. Patrick's Day" from Take Me Out to the Ball Game.

[41] In particular, he wanted to create a completely different image from that associated with Fred Astaire, not least because he believed his physique did not suit such refined elegance: "I used to envy his cool, aristocratic style, so intimate and contained.

"[13] From the mid-1940s through the early 1950s, his wife Betsy Blair and he organized weekly parties at their Beverly Hills home, and they often played an intensely competitive and physical version of charades, known as "The Game".

[16][42] He used his position on the board of directors of the Writers Guild of America West on a number of occasions to mediate disputes between unions and the Hollywood studios.