Charles George Gordon

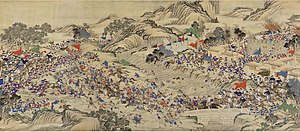

[31] After stopping in Shanghai, Gordon visited the Chinese countryside and was appalled at the atrocities committed by the Taipings against the local peasants, writing to his family he would love to smash this "cruel" army with its "desolating presence" that killed without mercy.

[36] Given Burgevine's alcoholism, open corruption, and tendency to engage in acts of mindless violence when drunk, the Chinese wanted "a man of good temper, of clean hands, and a steady economist" as his replacement.

[48] As Gordon travelled up and down the Yangtze River valley, he was appalled by the scenes of poverty and suffering he saw, writing in a letter to his sister: "The horrible furtive looks of the wretched inhabitants hovering around one's boats haunts me, and the knowledge of their want of nourishment would sicken anyone; they are like wolves.

Gordon declined all honours of financial gain, writing: "I know I shall leave China as poor as I entered it, but with the knowledge that, through my weak instrumentality, upwards of eighty to one hundred thousand lives have been spared.

[70] Typical of the men that Khedive Isma'il Pasha hired was Valentine Baker, a British Army officer dishonorably discharged after being convicted of raping a young woman in England that he had been asked to chaperon.

[81] Gordon chose not to meet Muteesa himself, instead sending his chief medical officer, a German convert to Islam, Dr. Emin Pasha, to negotiate a treaty wherein in exchange for allowing the Egyptians to leave the Buganda, the independence of the kingdom was recognised.

Urban wrote that, "Newspaper readers in Bolton or Beaminister had become enraged by stories about chained black children, cruelly abducted, being sold into slave markets", and Gordon's anti-slavery efforts contributed to his image as a saintly man.

[87] He accepted their offer, believing in Leopold's and Mackinnon's assurances their plans were purely philanthropic and they had no interest in exploiting Africans for profit[88] but the Khedive Isma'il Pasha wrote to him saying that he had promised to return, and that he expected him to keep his word.

[70] Licurgo Santoni, an Italian hired by the Egyptian state to run the Sudanese post office, wrote about Gordon's time as Governor-General that: as his exertions were not supported by his subordinates, his efforts remained fruitless.

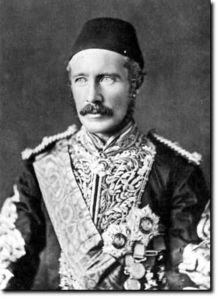

On 2 September 1877, Gordon clad in the full gold-braided ceremonial blue uniform of the Governor-General of the Sudan and wearing the tarboush (the type of fez reserved for a pasha), accompanied by an interpreter and a few bashi-bazouks, rode unannounced into the enemy camp to discuss the situation.

[64] Before Gordon boarded the ship at Alexandria that was to take him home, he sent off a series of long telegrams to various ministers in London full of Biblical verse and quotations that he said offered the solution to all of the problems of modern life.

[113] Gordon further advised the Qing court that it was unwise for the Manchu elite to live apart from and treat the Han Chinese majority as something less than human, warning that this not only weakened China in the present, but would cause a revolution in the future.

[120] Having been to all of those places and thus speaking with some authority, Gordon announced the "scandal" of poverty in Ireland could only be ended if the government were to buy the land from the Ascendency families, as the Anglo-Irish elite was known, and give it to their poor Irish tenant farmers.

[130] He accepted and returned to London to make preparations, but soon after his arrival, the British requested that he proceed immediately to the Sudan, where the situation had deteriorated badly after his departure — another revolt had arisen, led by the self-proclaimed Mahdi, Mohammed Ahmed.

It is often suggested that that campaign by William Randolph Hearst's paper that led to the US invasion of Cuba in 1898 was the world's first episode of this kind, but the British press deserves these dubious laurels for its actions a full fourteen years earlier".

[141] The man behind the campaign was the Adjutant General, Sir Garnet Wolseley—a skilled media manipulator who often leaked information to the press to effect changes in policy—and who was strongly opposed to Gladstone's policy of pulling out of the Sudan.

At Cairo, he received further instructions from Sir Evelyn Baring, and was appointed Governor-General with executive powers by the Khedive Tewfik Pasha, who also gave Gordon an edict ordering him to establish a government in the Sudan.

[147] Urban wrote that Gordon's "most stupid mistake" occurred when he revealed his secret orders at a meeting of tribal leaders on 12 February at Berber, explaining that the Egyptians were pulling out, leading to almost all of the Arab tribes of northern Sudan declaring their loyalty to the Mahdi.

"[150] Even Wolseley had cause to regret sending Gordon, as the general revealed himself to be a loose cannon whose press statements attacking the Liberal government were "obstructing rather than furthering his plans to take over the Sudan".

[153] Additionally, Gordon had guns and armoured plating attached to the paddle wheel steamers stationed at Khartoum to create his own private riverine navy that served as an effective force against the Ansar.

[167] Gordon waged a very vigorous defence, sending out his armoured steamers to engage the Ansar camps along the Blue Nile while he regularly made raids on the besiegers that often gave the Madhi's forces a "bloody nose".

To slow down the Ansar assaults, Gordon built primitive landmines out of water cans stuffed with dynamite and to confuse the enemy about his numbers, he put up wooden dummies in uniform along the walls of Khartoum facing the Blue Nile.

"[178] On 14 December 1884, Gordon wrote the last entry in his diary, which read: "Now MARK THIS, if the Expeditionary Force and I ask for no more than two hundred men, does not come in ten days, the town may fall; and I have done my best for the honour of our country.

[161] In his last weeks, those who knew Gordon described him as a chain-smoking, rage-filled, desperate man wearing a shabby uniform who spent hours talking to a mouse that he shared his office with when he was not attacking his Sudanese servants with his rattan cane during one of his rages.

[172] On 24 January, two of the steamers, under Sir Charles Wilson, carrying 20 soldiers of the Sussex Regiment wearing red tunics to clearly identify them as British, were sent on a purely reconnaissance mission to Khartoum, with orders from Wolseley not to attempt to rescue Gordon or bring him ammunition or food.

The most popular account of Gordon's death was that he put on his ceremonial gold-braided blue uniform of the Governor-General together with the Pasha's red fez and that he went out unarmed, except with his rattan cane, to be cut down by the Ansar.

[201] After the Battle of Omdurman, Kitchener opened a letter from the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, and for the first time learned the real purpose of the expedition had been to keep the French out of the Sudan and that "avenging Gordon" was merely a pretext.

He was unfamiliar with the comfortable indulgences typical of his social class and status; his clothing bordered on being threadbare, and he partook in frugal meals at a table equipped with a drawer, where he hastily concealed his bread and plate when impoverished visitors approached.

[221] When the Duke of Cambridge, the Army's commander, visited one of the forts under construction and praised Gordon for his work, he received the reply: "I had nothing to do with it, sir; it was built regardless of my opinion, and, in fact, I entirely disapprove of its arrangement and position".

Mark Urban argued that Gordon's final stand was "significant" because it was "a perversion of the democratic process" as he "managed to subvert government policy", making the beginning of a new era where decision-makers had to consider the power of media.