General anaesthetic

General anaesthetics are a structurally diverse group of compounds whose mechanisms encompass multiple biological targets involved in the control of neuronal pathways.

[2] General anesthetics, however, typically elicit several key reversible effects: immobility, analgesia, amnesia, unconsciousness, and reduced autonomic responsiveness to noxious stimuli.

[2][5] Induction and maintenance of general anesthesia, and the control of the various physiological side effects is typically achieved through a combinatorial drug approach.

The relative roles of different receptors is still under debate, but evidence exists for particular targets being involved with certain anaesthetics and drug effects.

[4] The receiver of the anesthesia primarily feels analgesia followed by amnesia and a sense of confusion moving into the next stage.

Indicators for stage III anesthesia include loss of the eyelash reflex as well as regular breathing.

[4] Aside from the clinically advantageous effects of general anesthetics, there are a number of other physiological consequences mediated by this class of drug.

Notably, a reduction in blood pressure can be facilitated by a variety of mechanisms, including reduced cardiac contractility and dilation of the vasculature.

This drop in blood pressure may activate a reflexive increase in heart rate, due to a baroreceptor-mediated feedback mechanism.

[3][4] Patients under general anesthesia are at greater risk of developing hypothermia, as the aforementioned vasodilation increases the heat lost via peripheral blood flow.

By and large, these drugs reduce the internal body temperature threshold at which autonomic thermoregulatory mechanisms are triggered in response to cold.

Inhalational anesthetics elicit bronchodilation, an increase in respiratory rate, and reduced tidal volume.

Compounded with a reduction in lower esophageal sphincter tone, which increases the frequency of regurgitation, patients are especially prone to asphyxiation while under general anesthesia.

Healthcare providers closely monitor individuals under general anesthesia and utilize a number of devices, such as an endotracheal tube, to ensure patient safety.

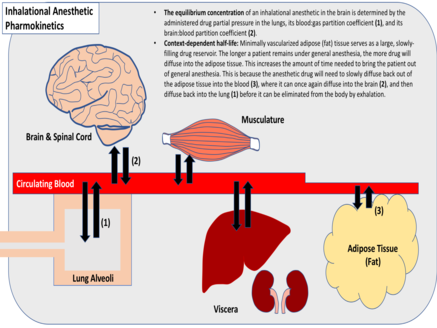

These characteristics facilitate their rapid preferential distribution into the brain and spinal cord, which are both highly vascularized and lipophilic.

Therefore, following administration of a single anesthetic bolus, duration of drug effect is dependent solely upon the redistribution kinetics.

When large quantities of an anesthetic drug have already been dissolved in the body's fat stores, this can slow its redistribution out of the brain and spinal cord, prolonging its CNS effects.

Respiratory rate and inspiratory volume will also affect the promptness of anesthesia onset, as will the extent of pulmonary blood flow.