Genoese navy

Through the 17th and 18th century the power of the Genoese navy and fleet declined, thanks to bankers and no longer merchants being the strongest economic force in the Republic.

[2] The Muslim incursion spurred the city to build strong harbor defenses, and renewed interest in an armed merchant marine to patrol the Ligurian Sea.

The young republic was as such dominated by the needs and desires of the merchant houses, and the navy was given a place of high importance in the new thalassocracy.

A High Admiral was appointed, and with the government coordinating the navy, Genoese traders and merchants came to dominate the Ligurian Sea in the 11th century.

As such, the 11th century fleet was relegated to protecting the trade of the great merchant houses of Genoa, which continued to dominate the politics and economy of the republic.

[3] After decades of disorder caused by the Norman conquest of southern Italy, the Genoese navy assisted in the capture of the city of Mahdia in 1087.

[6] The Lebanese town of Byblos came completely under Genoese control, and the republic was entitled to 1/3 of the crusader-controlled city of Acre's income.

[8] In the early 12th century the Genoese navy participated in the Pisan-led 1113–15 Balearic Islands expedition to suppress Majorcan piracy.

[12] In addition to supporting the wars in the Holy Land, the navy played a vital role in the Genoese rivalry with the nearby Republic of Pisa, which competed with Genoa for influence in Corsica and Sardinia.

[13] It was common for the Italian maritime states to prey on their rival's merchant shipping, and the Genoese navy was known to both suppress and participate in this practice.

The republic sided with the Pope (who was at the time in a dispute with the Holy Roman Emperor), and sent a fleet to transport a Guelph army to Rome in a show of support for the papal cause.

[16] During the conflict the Genoese navy was defeated in a series of pitched battles against Venice, and so it resorted to attacking merchant convoys instead of warships.

[16][17] This strategy proved highly effective and would become known as "War of the Chase" to the Genonese, in which faster Genoese galleys would outrun slower, better organized Venetian squadrons.

[18] The disastrous defeats at the hands of Pisa and Venice hindered Genoese ambitions, but also led to the creation of a dedicated naval force in Genoa.

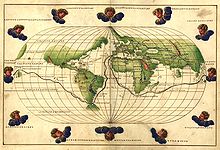

In 1266 Genoese merchants purchased the city of Kaffa from the Golden Horde and went on to establish further trading colonies in the Black Sea and Byzantine Empire.

While the status quo in the east was maintained, the Kingdom of Aragon was able to establish itself as a major rival to Genoese domination of the Western Mediterranean.

The Genoese navy lost vital sailors, ships, and was supplanted as the leading naval power in the Western Mediterranean by Aragon.

Genoa (with French support) launched a crusade against Tunisia in 1390, with the intent to protect Genoese trade colonies from Muslim pirates.

Despite this setback, Aragon prevailed in the conflict and Sicily came under Aragonese control, making passage through the Strait of Messina difficult and further disrupting Genoese naval activities.

The gradual loss of Imperial territory, coupled with the destruction of smaller Christian states such as Trebizond, Cyprus, and Amasra chipped away at Genoese mercantile interests in the Black Sea.

This act cut the Genoese navy off from its bases in the Black Sea, and Genoa found itself isolated from the colonies that had for centuries provided the republic access to Russia and Central Asia.

He returned from service as a mercenary captain in 1503 to encourage Genoa to resist French encroachment, but failed and was forced to flee the city.

After retiring from military service, Doria, who was genuinely devoted to his native city of Genoa, worked to re-establish the republic's independence, free of the interference of foreign powers.

While officially neutral during the French Revolutionary Wars, Genoa's close proximity to France allowed the larger country to continuously pressure the republic.

Both fleets were under the command of the office of the High Admiral, who was appointed by the ruler (either the doge, council, or duke depending on the era) of Genoa.

These ships possessed an advantage in terms of maneuverability when compared to purely sailing vessels, and their design allowed them to be produced relatively quickly.

[51][50] The fleet also made extensive use of Brigantines and Feluccas, small sailing ships which acted as scouts and raiders when the republic's galleys were unable to operate effectively.

The republic mandated that every galley in service be crewed with a barber - who also served as a surgeon - in order to maintain a standard of hygiene aboard the ship.

The Genoese Arsenal's extensive facilities were converted from military to civilian use following the Unification of Italy, leading to the port becoming a driving factor in Genoa's economic revival.

The oldest part of the arsenal became the foundation for the Galata - Museo del mare, a museum dedicated to the naval history of Genoa.