Geometric function theory

A fundamental result in the theory is the Riemann mapping theorem.

In the most common case the function has a domain and range in the complex plane.

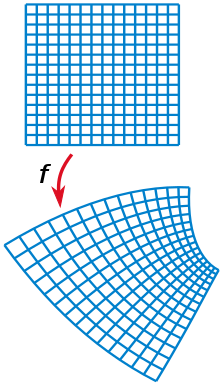

More formally, a map, is called conformal (or angle-preserving) at a point

Conformal maps preserve both angles and the shapes of infinitesimally small figures, but not necessarily their size or curvature.

In mathematical complex analysis, a quasiconformal mapping, introduced by Grötzsch (1928) and named by Ahlfors (1935), is a homeomorphism between plane domains which to first order takes small circles to small ellipses of bounded eccentricity.

Intuitively, let f : D → D′ be an orientation-preserving homeomorphism between open sets in the plane.

If f is continuously differentiable, then it is K-quasiconformal if the derivative of f at every point maps circles to ellipses with eccentricity bounded by K. If K is 0, then the function is conformal.

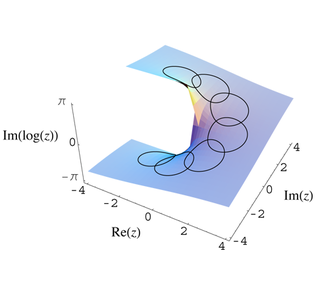

Analytic continuation often succeeds in defining further values of a function, for example in a new region where an infinite series representation in terms of which it is initially defined becomes divergent.

These may have an essentially topological nature, leading to inconsistencies (defining more than one value).

The case of several complex variables is rather different, since singularities then cannot be isolated points, and its investigation was a major reason for the development of sheaf cohomology.

Riemann surfaces can be thought of as deformed versions of the complex plane: locally near every point they look like patches of the complex plane, but the global topology can be quite different.

The main point of Riemann surfaces is that holomorphic functions may be defined between them.

[3] A holomorphic function on an open subset of the complex plane is called univalent if it is injective.

are two open connected sets in the complex plane, and is a univalent function such that

, proving "any two simply connected regions different from the whole plane

The Schwarz lemma, named after Hermann Amandus Schwarz, is a result in complex analysis about holomorphic functions from the open unit disk to itself.

It is however one of the simplest results capturing the rigidity of holomorphic functions.

Let D = {z : |z| < 1} be the open unit disk in the complex plane C centered at the origin and let f : D → D be a holomorphic map such that f(0) = 0.

Moreover, if |f(z)| = |z| for some non-zero z or if |f′(0)| = 1, then f(z) = az for some a in C with |a| (necessarily) equal to 1.The maximum principle is a property of solutions to certain partial differential equations, of the elliptic and parabolic types.

Specifically, the strong maximum principle says that if a function achieves its maximum in the interior of the domain, the function is uniformly a constant.

the Riemann–Hurwitz formula, named after Bernhard Riemann and Adolf Hurwitz, describes the relationship of the Euler characteristics of two surfaces when one is a ramified covering of the other.

It therefore connects ramification with algebraic topology, in this case.

It is a prototype result for many others, and is often applied in the theory of Riemann surfaces (which is its origin) and algebraic curves.

In the case of an (unramified) covering map of surfaces that is surjective and of degree N, we should have the formula That is because each simplex of S should be covered by exactly N in S′ — at least if we use a fine enough triangulation of S, as we are entitled to do since the Euler characteristic is a topological invariant.

What the Riemann–Hurwitz formula does is to add in a correction to allow for ramification (sheets coming together).

Now assume that S and S′ are Riemann surfaces, and that the map π is complex analytic.

The number n is called the ramification index at P and also denoted by eP.

Now let us choose triangulations of S and S′ with vertices at the branch and ramification points, respectively, and use these to compute the Euler characteristics.

Then S′ will have the same number of d-dimensional faces for d different from zero, but fewer than expected vertices.

Therefore, we find a "corrected" formula (all but finitely many P have eP = 1, so this is quite safe).