George Bellas Greenough

He also courted controversy, after using his presidential address in 1834 to cast aspersions on a paper on great earthquakes by Maria Graham.

[1] Greenough advocated an empirical approach to the early science; his scepticism of theoretical thinking courted controversy amongst some contemporaries, especially his doubts of the usefulness of fossils in correlating strata.

Greenough characterised himself as follows: ʻbright eyes, silver hair, large mouth, ears and feet; fondness for generalisation, for system and clearliness; great diligence, patience and zeal; goodnature but hasty; firmness of principle; hand for gardening.ʼ[2] Greenough was born in London, as George Bellas, named after his father, George Bellas, who had a profitable business in the legal profession as a proctor in Doctor's Commons, St Paul's Churchyard Doctors' Commons and some real estate in Surrey.

His mother was the only daughter of the apothecary Thomas Greenough, whose very successful business was located on Ludgate Hill near to St Paul's.

In order to improve his language skills Greenough attended the lectures of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach on natural history and these inspired a passion for mineralogy and geology.

He was elected member of parliament for the ("rotten"[11]) borough of Gatton, continuing to hold this seat until 1812,[8] although Hansard does not record he made any contributions to the House.

During the time he helped to found and forge the Geological Society, Greenough served in the militia in the Light Horse Volunteers of London and Westminster.

This was a corps of volunteers, originated by a group of city businessmen, and rather than being paid for their services members had to pay to join and maintain an annual subscription.

Greenough resigned his commission in 1819 as a matter of principle following the Peterloo massacre in Manchester, which he regarded as an abuse of military power for political ends.

He also became associated with a group of mineralogists to which Davy referred in a letter to William Pepys, dated 13 November 1807, when he said 'We are forming a little talking Geological Club'.

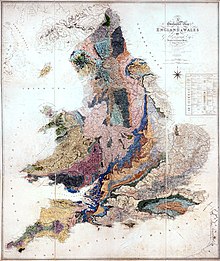

Members of the society out in the provinces of England and Wales submitted details of local rocks and strata which were collated by Greenough, entered in his notebooks and plotted on a topographical map.

Greenough was an inductivist in the Baconian tradition, so he eschewed 'theory' and systematically collected information and details with the aim of discovering the distribution of rocks.

For this reason Greenough wanted to dissociate himself and the Geological Society map from the man who was using fossils to identify strata.

[24][25][26] However original sources point to this narrative not being the case and indicate Smith was used by John Farey Sr., another 'practical man'(i.e. mineral surveyor), to prosecute Farey's own grievances against the Geological Society in an article in The Philosophical Magazine by which he both started and fuelled the story that Smith was disrespected and there was ill-feeling towards him by the Geological Society men and Greenough in particular.

[27] In the following issue Greenough replied, publicly declaring his view as being non-antagonistic by stating: "Your correspondent considers me, in common with many other persons, actuated by feelings of hostility towards Mr. Smith.

I respect him for the important services he has rendered to geology, and I esteem him for the example of dignity, meekness, modesty, and candour, which he continually, though ineffectually, exhibits to his self-appointed champion.

In 1852 Greenough produced a series of maps of Hindustan, mainly hydrographical, defining all the important elements of the ten water basins of the Indian Peninsula (for the Asiatic Society), and in 1854 a large-scale geological map of the whole of British India, published as a 'General Sketch of the Physical and Geological Features of British India.

Nevertheless, the influence of the Romantic poets is evident in his travels as his notebooks show how Greenough also found pleasure in allowing imagination and emotion to colour his response to grand landscapes.

[37] Greenough followed the system of Sir Joseph Banks to have weekly open hours for scientific meetings at his residence (first in Parliament Street and later at Grove House).

In 1827 this was included in a series of drawings of villas in the park by Thomas H. Shepherd, although the dedication misspells the owner's name as "Greenhough".

Greenough travelled on journeys to the continent throughout his life and at the age of 76 he set off for Italy and the East (Constantinople) with a view of connecting the geology of his researches on the geology of India with that of Europe, but he was taken ill en route with oedema ("dropsy"), probably caused by cardiac problems, and died at Naples on 2 April 1855.