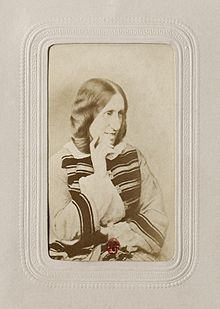

George Eliot

[3] She wrote seven novels: Adam Bede (1859), The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), Romola (1862–1863), Felix Holt, the Radical (1866), Middlemarch (1871–1872) and Daniel Deronda (1876).

Scandalously and unconventionally for the era, she lived with the married George Henry Lewes as his conjugal partner, from 1854 to 1878, and called him her husband.

Because she was not considered physically beautiful, Evans was not thought to have much chance of marriage, and this, coupled with her intelligence, led her father to invest in an education not often afforded to women.

In the religious atmosphere of the Misses Franklin's school, Evans was exposed to a quiet, disciplined belief opposed to evangelicalism.

[11] Thanks to her father's important role on the estate, she was allowed access to the library of Arbury Hall, which greatly aided her self-education and breadth of learning.

The people whom the young woman met at the Brays' house included Robert Owen, Herbert Spencer, Harriet Martineau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Through this society Evans was introduced to more liberal and agnostic theologies and to writers such as David Strauss and Ludwig Feuerbach, who cast doubt on the literal truth of Biblical texts.

In fact, her first major literary work was an English translation of Strauss's Das Leben Jesu kritisch bearbeitet as The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined (1846), which she completed after it had been left incomplete by Elizabeth "Rufa" Brabant, another member of the "Rosehill Circle".

As a product of their friendship, Bray published some of Evans's own earliest writing, such as reviews, in his newspaper the Coventry Herald and Observer.

[27] Eliot sympathized with the 1848 Revolutions throughout continental Europe, and even hoped that the Italians would chase the "odious Austrians" out of Lombardy and that "decayed monarchs" would be pensioned off, although she believed a gradual reformist approach to social problems was best for England.

In other essays, she praised the realism of novels that were being written in Europe at the time, an emphasis on realistic storytelling confirmed in her own subsequent fiction.

[37] Although female authors were published under their own names during her lifetime, she wanted to escape the stereotype of women's writing being limited to lighthearted romances or other lighter fare not to be taken very seriously.

Another factor in her use of a pen name may have been a desire to shield her private life from public scrutiny, thus avoiding the scandal that would have arisen because of her relationship with Lewes, who was married.

[39] In 1857, when she was 37 years of age, "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton", the first of the three stories included in Scenes of Clerical Life, and the first work of "George Eliot", was published in Blackwood's Magazine.

According to University of Victoria professor Lisa Surridge, Carlyle "stimulated Eliot's interest in German thought, encouraged her turn from Christian orthodoxy, and shaped her ideas on work, duty, sympathy, and the evolution of the self.

This public interest subsequently led to Mary Anne Evans Lewes's acknowledgment that it was she who stood behind the pseudonym George Eliot.

Her relationship with Lewes afforded her the encouragement and stability she needed to write fiction, but it would be some time before the couple were accepted into polite society.

The queen herself was an avid reader of all of Eliot's novels and was so impressed with Adam Bede that she commissioned the artist Edward Henry Corbould to paint scenes from the book.

[45][29] In 1870, she responded enthusiastically to Lady Amberley's feminist lecture on the claims of women for education, occupations, equality in marriage, and child custody.

[29] It would be wrong to assume that the female protagonists of her works can be considered "feminist", with the sole exception perhaps of Romola de' Bardi, who resolutely rejects the State and Church obligations of her time.

Eliot spent the next six months editing Lewes's final work, Life and Mind, for publication, and found solace and companionship with longtime friend and financial adviser John Walter Cross, a Scottish commission agent[47] 20 years her junior, whose mother had recently died.

[52] In 1980, on the centenary of her death, a memorial stone was established for her in the Poets' Corner between W. H. Auden and Dylan Thomas, with a quote from Scenes of Clerical Life: "The first condition of human goodness is something to love; the second something to reverence".

[56] Her memorial stone reads[57] Here lies the body of'George Eliot'Mary Ann CrossSeveral landmarks in her birthplace of Nuneaton are named in her honour.

From Adam Bede to The Mill on the Floss and Silas Marner, Eliot presented the cases of social outsiders and small-town persecution.

Romola, an historical novel set in late fifteenth century Florence, was based on the life of the Italian priest Girolamo Savonarola.

According to Clare Carlisle, who published a new biography on George Eliot in 2023,[61] the overdue publication of Spinoza's Ethics was a real shame, because it could have provided some illuminating cues for understanding the more mature works of the writer.

An example of this philosophy appeared in her novel Romola, in which Eliot's protagonist displayed a "surprisingly modern readiness to interpret religious language in humanist or secular ethical terms.

The religious elements in her fiction also owe much to her upbringing, with the experiences of Maggie Tulliver from The Mill on the Floss sharing many similarities with the young Mary Ann Evans.

This was not helped by the posthumous biography written by her husband, which portrayed a wonderful, almost saintly, woman totally at odds with the scandalous life people knew she had led.

In the 20th century she was championed by a new breed of critics, most notably by Virginia Woolf, who called Middlemarch "one of the few English novels written for grown-up people".