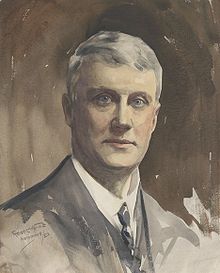

George Ernest Morrison

George Ernest Morrison (4 February 1862 – 30 May 1920) was an Australian journalist, political adviser to and representative of the government of the Republic of China during the World War I, and owner of the then largest Asiatic library ever assembled.

Three of Morrison's seven uncles were rectors of the Presbyterian Church, and two of the four others were principal (Alexander) and master (Robert) of Scotch College, Melbourne, where George Sr also taught mathematics for six months.

[1]: 6 During a vacation in early 1880, before his tertiary education, he walked from the heads at Queenscliff, Victoria, to Adelaide, following the coastline, a distance of about 650 miles (960 km) in 46 days.

After passing his first year, the 18-year-old took a vacation trip down the Murray River in a canoe, the Stanley, from Albury, New South Wales, to its mouth, a distance of some 2,000 kilometres (1,243 mi).

Written in a tone of wonder, and expressing "only the mildest criticism"; six months later, Morrison "revised his original assessment", describing details of the Lavinia's blackbirding operation, and sharply denouncing the slave trade in Queensland.

His articles, letters to the editor, and The Age editorials,[5] sparked considerable debate, leading to government intervention to eradicate what was, by Morrison's account, a slave trade.

[1]: 25–34 No doubt the country had been much opened up in the twenty years since Burke and Wills' well-funded failure, but the journey was nevertheless a remarkable feat, which stamped Morrison as a great natural bushman and explorer.

[2] He arrived at Melbourne on 21 April 1883 to find that during his journey Thomas McIlwraith, the premier of Queensland, had annexed part of New Guinea and was vainly endeavouring to secure the support of the British government for his action.

After graduation, Morrison travelled extensively in the United States, the West Indies, and Spain, where he became medical officer at the Rio Tinto mine.

Disguised under a hat with queue attached, he completed the journey in 100 days at a total cost of less than £30 (equivalent to A$5,196 in 2022),[1]: 70 which included the wages of two or three Chinese servants whom he picked up and changed on the way as he entered new districts.

After being refused a job at The Argus for being unable to "write up to [the editor's] standard", he turned down a lucrative offer to return to medical practice in Ballarat for ship's surgeon on a boat to London.

Unfortunately, his lack of knowledge in the Chinese language meant that he could not verify his stories and one author has suggested some of his reports contained bias and deliberate lies against China.

On the very day his communication arrived in London, 6 March 1898, The Times received a telegram from Morrison to say that Russia had presented a five-day ultimatum to China demanding the right to construct a railway to Port Arthur.

This was a triumph for The Times and its correspondent, but he had also shown prophetic insight in another phrase of his dispatch, when he stated that "the importance of Japan in relation to the future of Manchuria cannot be disregarded".

[2]: 11 The Boxer Uprising broke out soon after and, during the siege of the legations from June to August, Morrison, an acting-lieutenant, showed great courage, always ready to volunteer in the face of danger.

He was present at the entry of the Japanese into Port Arthur (now Lüshunkou) early in 1905, and represented The Times at the Portsmouth, New Hampshire, United States, peace conference.

In 1907, he crossed China from Peking to the French border of Tonkin, and, in 1910, rode from Honan City, Burma, across Asia to Andijan in Russian Turkestan, a journey of 3,750 miles (6,000 km), which was completed in 174 days.

[2]: 17 Polly Condit Smith, who was alongside Morrison during the Boxer uprising, wrote: "Although he was not a military man he had proved himself one of the most important members of the garrison, being always in motion and cognizant of what was going on everywhere, and by far the best informed person within the Legation quadrangle.

To this must be added a cool judgement, total disregard of danger and a perpetual sense of responsibility to help everyone to do his best – the most attractive at our impromptu mess, as dirty, happy and healthy a hero as one could find anywhere.

[2]: 18 A fictional account of Morrison's romantic affair with Mae Ruth Perkins was published in A Most Immoral Woman by Australian author Linda Jaivin in 2009.