George Lansbury

Apart from a brief period of ministerial office during the Labour government of 1929–31, he spent his political life campaigning against established authority and vested interests, his main causes being the promotion of social justice, women's rights, and world disarmament.

[2] Through his progressive-minded mother and grandmother, young George became familiar with the names of great contemporary reformers—Gladstone, Richard Cobden and John Bright—and began to read the radical Reynolds's Newspaper.

[7] During his adolescence and early adulthood, Lansbury was a regular attender at the public gallery at the House of Commons, where he heard and remembered many of Gladstone's speeches on the main foreign policy issue of the day, the "Eastern Question".

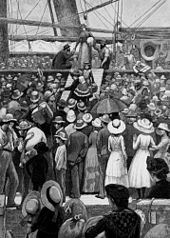

The London agent-general for Queensland depicted a land of boundless opportunities, with work for all; seduced by this appealing prospect, Lansbury and Bessie raised the necessary passage money, and in May 1884 set sail with their children for Brisbane.

His first job, breaking stone, proved to be too physically punishing; he moved to a better-paid position as a van driver, but was sacked when, for religious reasons, he refused to work on Sundays.

As a keen follower of the game he hoped to see the visiting English touring team play but, as Lansbury's biographer Raymond Postgate records, "he learned that cricket watching was not a pleasure for workmen".

[19] He continued to serve the Liberals, as an agent and local secretary, while expressing his socialism in a short-lived monthly radical journal, Coming Times, which he founded and co-edited with a fellow-dissident, William Hoffman.

In a letter published in the Pall Mall Gazette he made an open call to Bow and Bromley's Liberals to "shake themselves free of party feeling and throw the energy and ability they are now wasting on minor questions into ... securing the full rights of citizenship to every woman in the land".

[30] By 1892 the Liberals no longer felt like Lansbury's political home; most of his current associates were avowed socialists: William Morris, Eleanor Marx, John Burns and Henry Hyndman, founder of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF).

He preached a straightforward revolutionary doctrine: "The time has arrived", he informed an audience at Todmorden in Lancashire, "for the working classes to seize political power and use it to overthrow the competitive system and establish in its place state cooperation".

[38] In the general election of 1900 a pact with the Liberals in the Bow and Bromley constituency gave Lansbury, the SDF candidate, a straight fight against the Conservative incumbent, Walter Murray Guthrie.

Lansbury, together with Beatrice Webb of the Fabian Society, argued for the complete abolition of the Poor Laws and their replacement by a system that incorporated old age pensions, a minimum wage, and national and local public works projects.

[66] In October 1912, aware of the unbridgeable gap between his own position and that of his Labour colleagues, Lansbury resigned his seat to fight a by-election in Bow and Bromley on the specific issue of women's suffrage.

[70] Out of parliament, on 26 April 1913 Lansbury addressed a WSPU rally at the Albert Hall, and openly defended violent methods: "Let them burn and destroy property and do anything they will, and for every leader that is taken away, let a dozen step forward in their place".

[n 9] In the prevailing jingoistic mood, numerous readers looked to the Herald—reduced by wartime economies to a weekly format—to present a balanced news perspective, untainted by war fever and chauvinism.

Lansbury resigned the editorship and made the paper over to the Labour Party and the Trades Union Congress (TUC), although he continued to write for it and remained its titular general manager until 3 January 1925.

This conference brought a significant personal victory for Lansbury: the passage of the Local Authorities (Financial Provisions) Act, which equalised the poor relief burden across all the London boroughs.

[104] In 1925, free from the Daily Herald, he founded and edited Lansbury's Labour Weekly, which became a mouthpiece for his personal creed of socialism, democracy and pacifism until it merged with the New Leader in 1927 .

[129] As leader he began the process of reforming the party's organisation and machinery, efforts which resulted in considerable by-election and municipal election successes—including control of the LCC under Herbert Morrison in 1934.

[136] As fascism and militarism advanced in Europe, Lansbury's pacifist stance drew criticism from the trade union elements of his party—who controlled the majority of party conference votes.

His speech—a passionate exposition of the principles of Christian pacifism—was well received by the delegates, but immediately afterwards his position was destroyed by Ernest Bevin, the Transport and General Workers' Union leader.

[140] Union support ensured that the sanctions resolution was carried by a huge majority; Lansbury, realising that a Christian pacifist could no longer lead the party, resigned a few days later.

[144] [Hitler] appeared free of personal ambition ... wasn't ashamed of his humble start in life ... lived in the country rather than the town ... was a bachelor who liked children and old people ... and was obviously lonely.

[149] His mild and optimistic impressions of the European dictators were widely criticised as naïve and out of touch; some British pacifists were dismayed at Lansbury's meeting with Hitler,[150] while the Daily Worker accused him of diverting attention from the aggressive realities of fascist policies.

Observing that the cause to which he had dedicated his life was going down in ruins, he added: "I hope that out of this terrible calamity will arise a spirit that will compel people to give up the reliance on force.

[159] Nevertheless, his speeches in the House of Commons were often flavoured with historical and literary allusions, and he left behind a considerable body of writing on socialist ideas; Morgan refers to him as a "prophet".

Attlee also paid tribute to his former leader: "He hated cruelty, injustice and wrongs, and felt deeply for all who suffered ... [H]e was ever the champion of the weak, and ... to the end of his life he strove for that in which he believed".

[163] After the Second World War, a stained glass window designed by the Belgian artist Eugeen Yoors was placed in the Kingsley Hall community centre in Bow, as a memorial to Lansbury.

[159] A further enduring memorial, Attlee suggests, is the extent to which the then-revolutionary social policies that Lansbury began advocating before the turn of the 20th century had become accepted mainstream doctrine little more than a decade after his death.

Four years later, in May 1884, he took his wife and their three young children to Australia as emigrants with high hopes based on British government propaganda, which suggested plentiful work and a rosy life there.