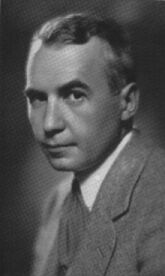

George Strock

George Strock (July 3, 1911 – August 23, 1977) was a photojournalist during World War II when he took a picture of three American soldiers who were killed during the Battle of Buna-Gona on the Buna beach.

[1] After high school, Strock photographed Hollywood celebrities, crime and sports for the Los Angeles Times before joining Life magazine in 1940.

[1] Strock attended John C. Fremont High School in South Central Los Angeles where he studied photojournalism under Clarence A. Bach, who had begun teaching the first such course in the United States in 1924.

[10] He shot images of the military at Fort Dix and Pensacola Naval Air Station and everyday civilian life.

Fellow Fremont High graduate and photographer Dick Pollard referred Strock, and Life began giving him assignments.

He was known to drink excessively, and in 1942, after returning to the United States, he was assigned to join a convoy departing San Francisco for Australia.

"In late January, 1943, Strock left Port Moresby with his negatives for Honolulu, but his plane was temporarily delayed when one of its propellers struck a tree upon takeoff.

The job of men like Strock is to bring the war back to us, so that we who are thousands of miles removed from the dangers and the smell of death may know what is at stake.

[14][19] Up until this time, the U.S. Office of Censorship only permitted the media to publish images of blanket-covered bodies and flag-draped coffins of dead U.S.

In Australia, General Douglas MacArthur threatened to court-martial any soldier who gave a correspondent an interview without official permission.

[26] Life Washington correspondent Cal Whipple felt that Strock's photograph was needed to inject a dose of reality on the home front which he thought was growing complacent about the war effort.

Whipple said, “I went from army captain to major to colonel to general, until I wound up in the office of an Assistant Secretary of the Air Corps, who decided, ‘This has to go to the White House.’”[19] Elmer Davis, Director of the Office of War Information, believed that the American public "had a right to be truthfully informed" about the war within the dictates of military security.

Davis asked President Roosevelt to lift the ban on publishing photographs of dead American soldiers on the battlefield.

Strock's image was the first photograph to depict American soldiers dead on the battlefield since the attack on Pearl Harbor 21 months before.

And the reason we print it now is that, last week, President Roosevelt and Elmer Davis and the War Department decided that the American people ought to be able to see their own boys as they fall in battle; to come directly and without words into the presence of their own dead...

[28] The image was described as a "stark depiction of the stillness of death, and then shocking when it became clear on second glance that maggots had claimed the body of one soldier, face down in the sand.

[33] In 1955 Strock's photograph of a couple courting in a crowded, overheated bar was selected by Edward Steichen for the world-touring Museum of Modern Art exhibition The Family of Man, that was seen by 9 million visitors.