Geothermal energy in Turkey

To reduce the emission of both carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, the fluid is sometimes completely reinjected back into the reservoir.

[10] Thousands of such hot springs and hundreds of spas have been used for tourism and health (such as balneotherapy for rheumatic diseases[11]) since ancient times, including by the Romans.

[13] In 1965, the government's Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration began the first geological and geophysical surveys in southwestern Turkey.

The Kızıldere geothermal reservoir, on the western branch of the Büyük Menderes Graben, was found in 1968 to be suitable for electricity generation.

A small 500 kW pilot power plant was built in 1974,[14] and free electricity distributed to nearby households.

[18][19] For plants started between 2010 and 2021 the Renewable Energy Support Scheme feed-in tariff was 10.5 US cent/kWh, guaranteed for ten years.

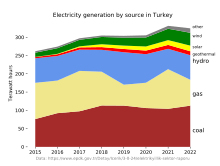

[21] By 2017 electricity generation capacity had been expanded over tenfold, to over 1 GW; and from 2009 to 2019 the number of geothermal power plants increased from 3 to 49.

[22][18] Down to a few kilometers under the surface (drilling has been done to almost 5 km[23]: 4 ) most rock is cooler than the boiling point of water, but there are a few high-temperature resources in the Menderes Massif,[14] up to almost 300 °C.

[28] The CO2 emissions from new geothermal plants in Turkey are some of the highest in the world, ranging from 900 to 1300 g/kWh[29] (similar to coal power) but gradually decline.

[24]: 4 Turkey is fourth in the world for geothermal power; with about half that of the United States, and slightly less than Indonesia and the Philippines.

[50] Electricity generation potential from hydrothermal (conventional geothermal rather than enhanced) was estimated at 4 GW in 2020, over double the actual capacity.

[26] Two-thirds of the installed capacity uses binary technology (hot water from the ground evaporates a fluid with a lower boiling point which drives the turbines) while the rest use the flash cycle (some of the high pressure and very hot water from the ground "flashes" to steam which drives the turbines directly).

[52] In 2019 Enel sponsored the 88KEYS Institute to conduct a public opinion survey in Aydın, the province with the most geothermal potential.

[31] However the carbon price in Iceland is the same as the EU Allowance (around 80 euros a tonne in mid-2022),[57] whereas in Turkey there is no immediate financial penalty for releasing it because the Turkish Emissions Trading System is not yet charging.

Geothermal has high upfront costs[58] and is financially risky,[59] but if public money is invested at an early stage of a project that gives private investors confidence to complete the financing.

[37][25] According to the Geothermal Power Plant Investors Association the cost of a kilometre deep well is about 1 million USD.

[70] Construction is an important part of the Turkish economy, and it has been suggested that the technology used to produce dry ice (solid carbon dioxide) at Kızıldere and Tuzla geothermal power plants could be adapted to capture CO2 emissions from cement production.