High Seas Fleet

Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz was the architect of the fleet; he envisioned a force powerful enough to challenge the Royal Navy's predominance.

Kaiser Wilhelm II, the German Emperor, championed the fleet as the instrument by which he would seize overseas possessions and make Germany a global power.

The primary component of the Fleet was its battleships, typically organized in eight-ship squadrons, though it also contained various other formations, including the I Scouting Group.

Following the German defeat in November 1918, the Allies interned the bulk of the High Seas Fleet in Scapa Flow, where it was ultimately scuttled by its crews in June 1919, days before the belligerents signed the Treaty of Versailles.

Implicit in Tirpitz's theory was the assumption that the British would adopt an offensive strategy that would allow the Germans to use mines and submarines to even the numerical odds before fighting a decisive battle between Heligoland and the Thames.

This would be supported by the eight Siegfried- and Odin classes of coastal defense ships, six large and eighteen small cruisers, and twelve divisions of torpedo boats, all assigned to the Home Fleet (Heimatflotte).

Rising international tensions, particularly as a result of the outbreak of the Boer War in South Africa and the Boxer Uprising in China, allowed Tirpitz to push through an expanded fleet plan in 1900.

Admiral John Fisher, who became the First Sea Lord and head of the Admiralty in 1904, introduced sweeping reforms in large part to counter the growing threat posed by the expanding German fleet.

Training programs were modernized, old and obsolete vessels were discarded, and the scattered squadrons of battleships were consolidated into four main fleets, three of which were based in Europe.

Britain also made a series of diplomatic arrangements, including an alliance with Japan that allowed a greater concentration of British battleships in the North Sea.

[9] Fisher's reforms caused serious problems for Tirpitz's plans; he counted on a dispersal of British naval forces early in a conflict that would allow Germany's smaller but more concentrated fleet to achieve a local superiority.

Ships capable of battle with Dreadnought would need to be significantly larger than the old pre-dreadnoughts, which increased their cost and necessitated expensive dredging of canals and harbors to accommodate them.

[6] The Reichstag passed a second amendment to the Naval Law in March 1908 to provide an additional billion marks to cope with the growing cost of the latest battleships.

[18] The British, however, did not accommodate Tirpitz's projections; from his appointment as the First Sea Lord in 1904, Fisher began a major reorganization of the Royal Navy.

He concentrated British battleship strength in home waters, launched the Dreadnought revolution, and introduced rigorous training for the fleet personnel.

Admiral Prince Heinrich of Prussia, Wilhelm II's brother, became the first commander of the High Seas Fleet; his flagship was SMS Deutschland.

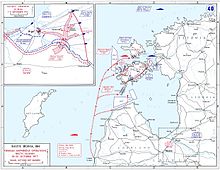

[42] Despite the rising international tensions following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June, the High Seas Fleet began its summer cruise to Norway on 13 July.

[44] On the evening of 15 December, the German battle fleet of some twelve dreadnoughts and eight pre-dreadnoughts came to within 10 nmi (19 km; 12 mi) of an isolated squadron of six British battleships.

[47] Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer became Commander in chief of the High Seas Fleet on 18 January 1916 when Pohl became too ill to continue in that post.

[51] Admiral Scheer's fleet, composed of 16 dreadnoughts, six pre-dreadnoughts, six light cruisers, and 31 torpedo boats departed the Jade early on the morning of 31 May.

[74] On 18 September, the order was issued for a joint operation with the army to capture Ösel and Moon Islands; the primary naval component was to comprise its flagship, Moltke, and the III and IV Battle Squadrons of the High Seas Fleet.

The previous day, the Admiralstab had ordered the cessation of naval actions and the return of the dreadnoughts to the High Seas Fleet as soon as possible.

The operation called for Hipper's battlecruisers to attack the convoy and its escorts on 23 April while the battleships of the High Seas Fleet stood by in support.

The Germans reached their defensive minefields early on 25 April, though approximately 40 nmi (74 km; 46 mi) off Heligoland Moltke was torpedoed by the submarine E42; she successfully returned to port.

[84] Following the capitulation of Germany in November 1918, most of the High Seas Fleet, under the command of Rear Admiral Ludwig von Reuter, were interned in the British naval base of Scapa Flow.

[83] Prior to the departure of the German fleet, Admiral Adolf von Trotha made clear to Reuter that he could not allow the Allies to seize the ships, under any conditions.

On the morning of 21 June, the British fleet left Scapa Flow to conduct training maneuvers, and at 11:20 Reuter transmitted the order to his ships.

[85] Out of the interned fleet, only one battleship, Baden, three light cruisers, and eighteen destroyers were saved from sinking by the British harbor personnel.

The Royal Navy, initially opposed to salvage operations, decided to allow private firms to attempt to raise the vessels for scrapping.

[91] The High Seas Fleet, particularly its wartime impotence and ultimate fate, strongly influenced the later German navies, the Reichsmarine and Kriegsmarine.