Gessner Harrison

He had been raised as a staunch Christian, and while his devotion invited the reproval of many classmates, it once occasioned a compliment from the university's founder, Thomas Jefferson.

"[3] He was among the earliest enrollees for the premier term of the University of Virginia in 1825—his older brother Edward and friend Henry Tutwiler entered as well.

Her father was George Tucker, then professor of Moral Philosophy at the university, following oddly a lifestyle of social and financial delinquencies.

[6] Harrison and wife had ten children, three of whom married university professors and joined their parents as residents of Jefferson's "Academical Village;" amongst them was women's rights advocate Mary Stuart Smith (1834–1917).

[3] According to biographer and colleague Broadus, as a husband and father, Harrison “was of great courage, both physical and moral,” but possessed “a delicate consideration for the feelings of others;”[7] he preferred a quiet, self-disciplined, erudite life.

[8] As he sought to find his place among the older, esteemed faculty members, handpicked by Jefferson and Madison, Harrison endeavored to overcome his feeling of inferiority.

[9]In a letter to Prof. Long, he confessed he felt ill-equipped in "converting my stock of information, which is not the greatest, into a useful instruction to my class," and lamented his "many deficiencies" as a professor.

[11] The behavioral problems were in large part due to the faculty maintaining a narrow focus upon lessons and examinations, to the exclusion of personal interaction with their students.

[2] Over the course of the next decade, professors' homes were vandalized and they were repeatedly confronted by student criminals armed with weapons and using profane, violent language.

[9] In 1839 Harrison was the victim of an egregious assault at the hands of two students, Thomas Russell and William Binford, who had just been expelled for “gross violations” of university rules.

Another student finally intervened and halted the attack, but when Harrison rebuked the perpetrators, they renewed the whipping before ultimately fleeing the city on horseback.

Broadus indicates that the university board adopted, and Harrison as faculty chairman executed, "a method of discipline, combining liberty and law, which in judicious hands was attended with admirable results.

Harrison thus described the event: Professor Davis in the vigor of health, and in the meridian of life, was shot down before his own door-sill in the wantonness of ruffian malice, when he had no suspicion of danger, was without the means of injury or defense, and when his only provocation was an unsuccessful attempt to discover who had disturbed his domestic peace and violated the laws of the University.

[10] When Harrison encountered students with poor classics preparation in the lecture hall, he insisted that language fundamentals not be neglected, even at the expense of developing more advanced concepts.

"[9] Harrison once lamented to a successor, "I suspect you'll have a lot such as mine; you will spend your life clearing the ground and laying foundations, mostly out of sight, on which more fortunate men shall build.

In the syllabus, Harrison included history, in order to show that the physical and historical peculiarities of Italy and Greece contributed to the character of the people and the formation of their languages.

Harrison supported the advance of this scientific approach in American comparative grammar, eventually applying its principles to the striking similarities between the ancient Sanskrit language of India and that of Latin and Greek.

Basil Gildersleeve and biographer Merrow E. Sorley, Harrison's keen interest led him to promote several innovative principles even before they were taken up by the German or English schools.

While Harrison's colleagues had praise for these works, their very specialized nature limited the circle of interested readers, and sales barely covered expenses.

Owing to the sometimes tedious nature of his subject, he was ready to employ a spontaneous, homespun humor, which on occasion became “as racy as it was peculiar.”[12] Harrison's professorial work ethic was self-defeating over time, as he failed to limit his workload to a manageable size.

They were deemed invaluable for an educator, who was believed to profit from an exchange of ideas and a personal review of events beyond that provided by newspapers and periodicals.

[2] Harrison was forced to confront an inability to make ends meet on his $3,000 annual salary, in light of the expenses of his considerably large family.

"[4] That year the students presented him with a silver pitcher and goblets "as a Memorial of their high regard and esteem;" they are still used at university library events.

[4] Harrison proceeded to purchase land in nearby Nelson County, and there instituted the Locust Grove Academy, where he enrolled 100 boys, some of them sons of former students from the university.

All of his then adult sons joined the Confederate army;[1] one, Charles Carter, returned home in 1861 with camp fever, and Harrison assumed the role of caregiver.

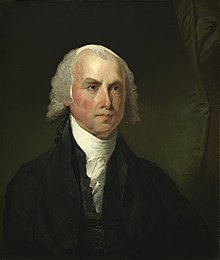

Harrison's predecessor and mentor