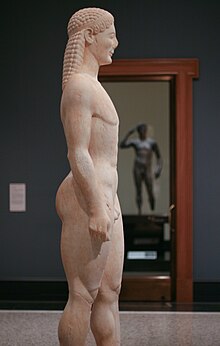

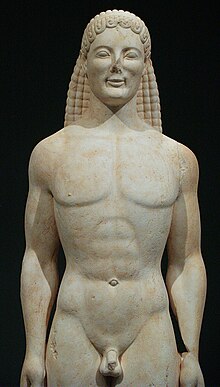

Getty kouros

[1] The dolomitic marble sculpture was bought by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, in 1985 for ten million dollars and first exhibited there in October 1986.

Subsequent demonstration of an artificial means of creating the de-dolomitization observed on the stone has prompted a number of art historians to revise their opinions of the work.

[6] The kouros first appeared on the art market in 1983 when the Basel dealer Gianfranco Becchina offered the work to the Getty's curator of antiquities, Jiří Frel.

Amongst the papers was a suspect 1952 letter allegedly from Ernst Langlotz, then the preeminent scholar of Greek sculpture, remarking on the similarity of the kouros to the Anavyssos youth in Athens (NAMA 3851).

The development of kouroi as delineated by Gisela Richter[10] suggests the date of the Getty youth diminishes from head to feet: At its top, the hair is braided into a wig-like mass of 14 strands, each of which ends in a triangular point.

Despite being of Thasian marble, the kouros cannot be securely ascribed to an individual workshop of northern Greece nor indeed to any ancient regional school of sculpture.

The oval plinth is an unusual shape and larger than in other examples, suggesting the figure was free-standing rather than fixed with lead in a separate base.

That the Getty kouros cannot be identified with any one local atelier does not disqualify it as a genuine, but if real it admits a lectio difficilior into the corpus of archaic sculpture.

Though the surface is weathered (or artificially abraded) and it is not clear if emery was used, there are heavy claw marks on the plinth and the use of a point in some of the finer detailing.

The first was by Norman Herz, a professor of geology at the University of Georgia, who measured the carbon and oxygen isotope ratios, and traced the stone to the island of Thasos.

His isotopic analysis revealed that δ18O = -2.37 and δ13C = +2.88, which from database comparison admitted one of five possible sources: Denizli, Doliana, Marmara, Mylasa, or Thasos-Acropolis.

He showed that the dolomite surface of the sculpture had undergone a process called de-dolomitization, in which the magnesium content had been leached out, leaving a crust of calcite, along with other minerals.