Great auk

It bred on rocky, remote islands with easy access to the ocean and a plentiful food supply, a rarity in nature that provided only a few breeding sites for the great auks.

During the non-breeding season, the auk foraged in the waters of the North Atlantic, ranging as far south as northern Spain and along the coastlines of Canada, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, Ireland, and Great Britain.

Analysis of mtDNA sequences has confirmed morphological and biogeographical studies suggesting that the razorbill is the closest living relative of the great auk.

The oldest known fossil records of the modern great auk are from the Boxgrove Palaeolithic site of England and Lower Town Hill Formation of Bermuda, both of which are dated to the Middle Pleistocene at least 400,000 years BP.

[7][8] The Pliocene sister species, Pinguinus alfrednewtoni, and molecular evidence show that the three closely related genera diverged soon after their common ancestor, a bird probably similar to a stout Xantus's murrelet, had spread to the coasts of the Atlantic.

[11] The following cladogram shows the placement of the great auk among its closest relatives, based on a 2004 genetic study:[12] Alle alle (little auk) Uria aalge (common murre) Uria lomvia (thick-billed murre) Alca torda (razorbill) Pinguinus impennis (great auk) Brachyramphus marmoratus (marbled murrelet) Brachyramphus brevirostris (Kittlitz's murrelet) Cepphus grylle (black guillemot) Cepphus columba (pigeon guillemot) Cepphus carbo (spectacled guillemot) Pinguinus alfrednewtoni was a larger, and also flightless, member of the genus Pinguinus that lived during the Early Pliocene.

[13] Known from bones found in the Yorktown Formation of the Lee Creek Mine in North Carolina, it is believed to have split, along with the great auk, from a common ancestor.

[14] The great auk was one of the 4,400 animal species formally described by Carl Linnaeus in his eighteenth-century work Systema Naturae, in which it was given the binomial Alca impennis.

When European explorers discovered what today are known as penguins in the Southern Hemisphere, they noticed their similar appearance to the great auk and named them after this bird, although biologically, they are not closely related.

[23] Standing about 75 to 85 centimetres (30 to 33 in) tall and weighing approximately 5 kilograms (11 lb) as adult birds,[24] the flightless great auk was the second-largest member of both its family and the order Charadriiformes overall, surpassed only by the mancalline Miomancalla.

[35] In the eastern Atlantic, the southernmost records of this species are two isolated bones, one from Madeira[38] and another from the Neolithic site of El Harhoura 2 in Morocco.

[40][22]: 29 The rookeries of the great auk were found from Baffin Bay to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, across the far northern Atlantic, including Iceland, and in Norway and the British Isles in Europe.

[20]: 312 The nesting sites also needed to be close to rich feeding areas and to be far enough from the mainland to discourage visitation by predators such as humans and polar bears.

[43] After the chicks fledged, the great auk migrated north and south away from the breeding colonies and they tended to go southward during late autumn and winter.

Based on remains associated with great auk bones found on Funk Island and on ecological and morphological considerations, it seems that Atlantic menhaden and capelin were their favoured prey.

[40] These colonies were extremely crowded and dense, with some estimates stating that there was a nesting great auk for every 1 square metre (11 sq ft) of land.

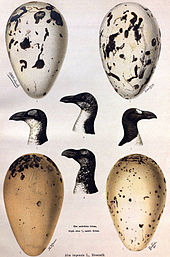

[19][22]: 35 The egg was yellowish white to light ochre with a varying pattern of black, brown, or greyish spots and lines that often were congregated on the large end.

[22]: 36 A person buried at the Maritime Archaic site at Port au Choix, Newfoundland, dating to about 2000 BC, was found surrounded by more than 200 great auk beaks, which are believed to have been part of a suit made from their skins, with the heads left attached as decoration.

Prior to that, hunting by local natives may be documented from Late Stone Age Scandinavia and eastern North America,[52] as well as from early fifth century Labrador, where the bird seems to have occurred only as stragglers.

[b] By the mid-sixteenth century, the nesting colonies along the European side of the Atlantic were nearly all eliminated by humans killing this bird for its down, which was used to make pillows.

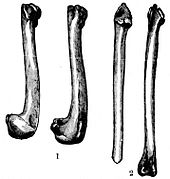

[10] Although thousands of isolated bones were collected from nineteenth century Funk Island to Neolithic middens, only a few complete skeletons exist.

[10] A specimen was bought in 1971 by the Icelandic Museum of National History for £9000, which placed it in the Guinness Book of Records as the most expensive stuffed bird ever sold.

While Kingsley portrays the extinction as sad, he provides his opinion that "there are better things come in her place," namely human colonization of the islands for the cod fishing industry, which would serve to feed the poor.

"[citation needed] Enid Blyton's The Island of Adventure (1944) sends one of the protagonists on a failed search for what he believes is a lost colony of the species.

In the short story The Harbor-Master by Robert W. Chambers, the discovery and attempted recovery of the last known pair of great auks is central to the plot (which also involves a proto-Lovecraftian element of suspense).

The story first appeared in Ainslee's Magazine (August 1898)[70] and was slightly revised to become the first five chapters of Chambers' episodic novel In Search of the Unknown, (Harper and Brothers Publishers, New York, 1904).

Penguin Island, a 1908 French satirical novel by the Nobel Prize winning author Anatole France, narrates the fictional history of a great auk population that is mistakenly baptized by a nearsighted missionary.

He associates the great auk with the mythical roc as a method of formally returning the main character to a sleepy land of fantasy and memory.

[73] Night of the Auk, a 1956 Broadway drama by Arch Oboler, depicts a group of astronauts returning from the Moon to discover that a full-blown nuclear war has broken out.

[77] The great auk is the subject of a ballet, Still Life at the Penguin Café (1988),[78] and a song, "A Dream Too Far", in the ecological musical Rockford's Rock Opera (2010).