Gioachino Greco

Gioachino Greco (c. 1600 – c. 1634), surnamed Cusentino and more frequently il Calabrese,[2] was an Italian chess player and writer.

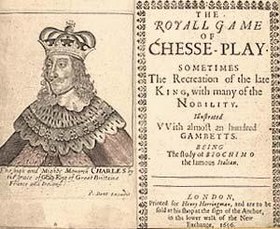

[5] Greco's writing was in the form of manuscripts for his patrons, in which he outlined the rules of chess, gave playing advice, and presented instructive games.

One prominent writer, Willard Fiske, even suggests (in The Book of the First American Chess Congress, 1859) that Greco was born in Morea, Greece, before moving to Calabria.

Greco apparently showed an early aptitude for chess, leaving home uneducated[10] and at a young age to make a living abroad.

[11] By 1620 Greco had become experienced enough to write his earliest dated manuscript, Trattato Del Nobilissimo Gioco De Scacchi...,[12] copies of which were given to his patrons in Rome.

[12] By 1622 Greco was travelling to England with a large sum of money; in Paris he had gained the equivalent of 5,000 crowns.

During his stay in London, Greco began recording entire chess games rather than single instructive positions, as had been the usual manner.

[16] Not one to remain in one place for long, Greco left Paris for the court of Philip IV in Spain.

[17] By this point Greco had shown himself to be the greatest player in Europe with victories over the champions of Rome, Paris, London, and Madrid.

[17] Greco was a remarkable chess player who lived during the era between Ruy López de Segura and François-André Danican Philidor.

[15] They are also valuable examples of the Italian Romantic school of chess, in which development and material are eschewed in favour of aggressive attacks on the opponent's king.

Greco paved the way for many of the attacking legends of the Romantic era, such as Philidor, Adolf Anderssen, and Paul Morphy.

[4] In particular, Le Jeu Des Eschets, published in Paris 1669 became the principal source for the later English editions by William Lewis (1819) and Louis Hoffmann (1900).

[23] Greco also describes the necessity of announcing check to one's opponent (still common in informal play but not in competition) and the disgrace of what he calls a "blind Mate" – a checkmate given but not noticed.

[24] The "Lawes of Chesse" were also not entirely standardized in Greco's time; for that reason, the rules as published by Beale would have been meant for a specific population.