Glass

Because it is often transparent and chemically inert, glass has found widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in window panes, tableware, and optics.

The earliest known glass objects were beads, perhaps created accidentally during metalworking or the production of faience, which is a form of pottery using lead glazes.

Due to chemical bonding constraints, glasses do possess a high degree of short-range order with respect to local atomic polyhedra.

Obsidian is a common volcanic glass with high silica (SiO2) content formed when felsic lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly.

[17] Vitrification of quartz can also occur when lightning strikes sand, forming hollow, branching rootlike structures called fulgurites.

[19] Edeowie glass, found in South Australia, is proposed to originate from Pleistocene grassland fires, lightning strikes, or hypervelocity impact by one or several asteroids or comets.

[20] Naturally occurring obsidian glass was used by Stone Age societies as it fractures along very sharp edges, making it ideal for cutting tools and weapons.

[21] Archaeological evidence suggests that the first true synthetic glass was made in Lebanon and the coastal north Syria, Mesopotamia or ancient Egypt.

[23][24] The earliest known glass objects, of the mid-third millennium BC, were beads, perhaps initially created as accidental by-products of metalworking (slags) or during the production of faience, a pre-glass vitreous material made by a process similar to glazing.

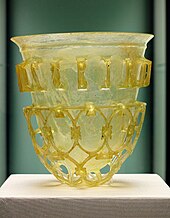

[31] Glass objects have been recovered across the Roman Empire[32] in domestic, funerary,[33] and industrial contexts,[34] as well as trade items in marketplaces in distant provinces.

By the 14th century, architects were designing buildings with walls of stained glass such as Sainte-Chapelle, Paris, (1203–1248) and the East end of Gloucester Cathedral.

[43] During the 13th century, the island of Murano, Venice, became a centre for glass making, building on medieval techniques to produce colourful ornamental pieces in large quantities.

[56] The key optical properties refractive index, dispersion, and transmission, of glass are strongly dependent on chemical composition and, to a lesser degree, its thermal history.

Even with this lower viscosity, the study authors calculated that the maximum flow rate of medieval glass is 1 nm per billion years, making it impossible to observe in a human timescale.

[68][81] Lead glass has a high elasticity, making the glassware more workable and giving rise to a clear "ring" sound when struck.

[101] Experimental evidence indicates that the system Al-Fe-Si may undergo a first-order transition to an amorphous form (dubbed "q-glass") on rapid cooling from the melt.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images indicate that q-glass nucleates from the melt as discrete particles with uniform spherical growth in all directions.

While x-ray diffraction reveals the isotropic nature of q-glass, a nucleation barrier exists implying an interfacial discontinuity (or internal surface) between the glass and melt phases.

[105] Molecular liquids, electrolytes, molten salts, and aqueous solutions are mixtures of different molecules or ions that do not form a covalent network but interact only through weak van der Waals forces or transient hydrogen bonds.

In a mixture of three or more ionic species of dissimilar size and shape, crystallization can be so difficult that the liquid can easily be supercooled into a glass.

This may be achieved manually by glassblowing, which involves gathering a mass of hot semi-molten glass, inflating it into a bubble using a hollow blowpipe, and forming it into the required shape by blowing, swinging, rolling, or moulding.

While hot, the glass can be worked using hand tools, cut with shears, and additional parts such as handles or feet attached by welding.

[130] These systems use stainless steel fittings countersunk into recesses in the corners of the glass panels allowing strengthened panes to appear unsupported creating a flush exterior.

[135] For electronics applications, glass can be used as a substrate in the manufacture of integrated passive devices, thin-film bulk acoustic resonators, and as a hermetic sealing material in device packaging,[136][137] including very thin solely glass based encapsulation of integrated circuits and other semiconductors in high manufacturing volumes.

[138] Glass is an important material in scientific laboratories for the manufacture of experimental apparatus because it is relatively cheap, readily formed into required shapes for experiment, easy to keep clean, can withstand heat and cold treatment, is generally non-reactive with many reagents, and its transparency allows for the observation of chemical reactions and processes.

[139][140] Laboratory glassware applications include flasks, Petri dishes, test tubes, pipettes, graduated cylinders, glass-lined metallic containers for chemical processing, fractionation columns, glass pipes, Schlenk lines, gauges, and thermometers.

[141][139] Although most standard laboratory glassware has been mass-produced since the 1920s, scientists still employ skilled glassblowers to manufacture bespoke glass apparatus for their experimental requirements.

[56] The 19th century saw a revival in ancient glassmaking techniques including cameo glass, achieved for the first time since the Roman Empire, initially mostly for pieces in a neo-classical style.

[143] Louis Comfort Tiffany in America specialised in stained glass, both secular and religious, in panels and his famous lamps.

Techniques for producing glass art include blowing, kiln-casting, fusing, slumping, pâte de verre, flame-working, hot-sculpting and cold-working.