Engraved glass

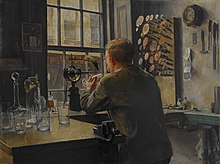

Engraving wheels are traditionally made of copper, with a linseed oil and fine emery powder mixture used as an abrasive.

The scratches and small dots made in this method can, in the hands of a skilled artist, be used to produce images of astonishing clarity and detail.

Abrasive is sprayed through a sandblasting gun onto glass which is masked up by a piece of stencil in order to produce inscriptions or images.

[6] Modern laser engraving on glass is another technique, generally only used for decorative purposes mechanically, for example to reproduce images on mirrors.

Engraving on Roman glass was mostly of ornamental patterns, but some figurative images were made, apparently from the 2nd century AD onwards, more often on bowls or plates than cups.

Most Venetian glass aimed at extreme thinness and delicacy, making it risky to attempt engraving, which was only done lightly with a diamond point.

This period coincided with the development in gem-cutting of the modern facet-cut diamond, making the essential diamond-point tool readily to hand for many of the wealthy.

[16] In England Jacob Verzelini, a Venetian glassmaker already working in London, was granted a monopoly for 21 years in 1574 over Venetian-style vessel glass.

His workshop developed a style with a large amount of simple but attractive engraving, much of it floral, and with the shapes filled in with parallel lines throughout.

Caspar Lehmann, a gem-cutter perhaps from Munich, is usually considered the first to engrave glass this way, after arriving in Prague in 1588.

[18] Prague had the court of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, a significant patron of Northern Mannerism in several of the arts.

The Habsburg court moved to Vienna after Rudolf's death but the Bohemian glass industry continued to grow in strength, reaching a peak of importance in the 18th century.

Glassworks there were often started or promoted by the owners of great estates; the requirement for large amounts of wood for the kilns assisted the clearance of forests for agricultural land.

[22] Caspar Lehmann's pupil Georg Schwanhardt moved from Prague to his native city of Nuremberg in 1622, and founded a workshop which lasted over a century, continued by his family and others.

The engraved decoration, normally restricted to the bowl and top of the cover, included a wide range of subjects, drawing from, but not exactly copying, contemporary prints.

[24] The exact use of the typical covered cup (pokale) is not entirely certain; it is unclear how often they were made in sets, and whether they were used often, or reserved for very formal feasts and toasting.

The German strapwork style known as Laub- und bandelwerk became common, as it did in porcelain from Meissen and Vienna from about the 1730s, but tended to become over-elaborate.

[28] In the 18th century the tax collector Frans Greenwood was the first to use the stipple engraving technique to make virtually all of his images, which were mostly figure subjects drawn from prints.

Like many Dutch engravers he preferred to use the slightly less brittle "English" type of lead glass developed by George Ravenscroft some decades before, though it now appears that this was by his time also being made on the continent, at Middelburg and elsewhere.

[43] The Beilby family workshop, active in Newcastle on Tyne between 1757 and 1778 are famous for their enamelled glass, much of it using only white, so achieving a similar effect to engraving.

[45] Glass-engraved figurative images as the primary decorative element on a particular object was less common in much of the Western world than before, with Bohemia the main exception.

Initially much of it focused on landscape subjects, in a pastoral and slightly Romantic mood whose influences included the painter and printmaker Samuel Palmer (1805–1881), whose early work was being rediscovered.

The innovative style he later developed involved engraving both the inner and outer sides of the glass, giving a sense of depth.

Especially after World War II in Britain, there were also a number of larger architectural engravings, often featuring figures nearly as large as life-size, executed on windows or glass screens.

Hutton's other commissions for monumental glass included work at Guildford Cathedral, the national Library and Archives Canada, and many other sites around Britain and the world.

A set of figures of the population of Roman London, completed in 1960 for a now-demolished office block, were relocated to Bank Underground station.

[60] James Denison-Pender, mostly a stipple engraver, mentioned in an interview that traditional goblets are now very difficult to sell, while the market favours works on flat glass.