Gliding flight

However, gliding can be achieved with a flat (uncambered) wing, as with a simple paper plane,[2] or even with card-throwing.

However, some aircraft with lifting bodies and animals such as the flying snake can achieve gliding flight without any wings by creating a flattened surface underneath.

Most winged aircraft can glide to some extent, but there are several types of aircraft designed to glide: The main human application is currently recreational, though during the Second World War military gliders were used for carrying troops and equipment into battle.

The design of all three types enables them to repeatedly climb using rising air and then to glide before finding the next source of lift.

Large birds are notably adept at gliding, including: Like recreational aircraft, birds can alternate periods of gliding with periods of soaring in rising air, and so spend a considerable time airborne with a minimal expenditure of energy.

This form of arboreal locomotion, is common in tropical regions such as Borneo and Australia, where the trees are tall and widely spaced.

In flying squirrels, the patagium stretches from the fore- to the hind-limbs along the length of each side of the torso.

[4] This gliding flight is regulated by changing the curvature of the membrane or moving the legs and tail.

After thrusting its body up and away from the tree, it sucks in its abdomen and flaring out its ribs to turn its body into a "pseudo concave wing",[11] all the while making a continual serpentine motion of lateral undulation[12] parallel to the ground[13] to stabilise its direction in mid-air in order to land safely.

[16] Flying lizards of the genus Draco are capable of gliding flight via membranes that may be extended to create wings (patagia), formed by an enlarged set of ribs.

Characteristics of the Old World species include "enlarged hands and feet, full webbing between all fingers and toes, lateral skin flaps on the arms and legs Three principal forces act on aircraft and animals when gliding:[20] As the aircraft or animal descends, the air moving over the wings and body generates lift perpendicular to the motion and drag parallel to the motion.

[21] Even though the weight causes the glider to descend, if the air is rising faster than the sink rate, there will be a gain of altitude.

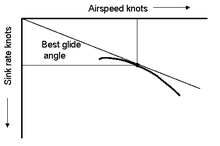

At low speeds an aircraft has to generate lift with a higher angle of attack, leading to greater induced drag.

As lift increases steadily until the critical angle, it is normally the point where the combined drag is at its lowest, that the wing or aircraft is performing at its best L/D.

Pilots fly faster to get quickly through sinking air, and when heading into wind to optimise the glide angle relative to the ground.

To achieve higher speed across country, gliders (sailplanes) are often loaded with water ballast to increase the airspeed and so reach the next area of lift sooner.

If the areas of lift are strong on the day, the benefits of ballast outweigh the slower rate of climb.

A low airspeed also improves its ability to turn tightly in the centre of the rising air where the rate of ascent is greatest.

A sink rate of approximately 1.0 m/s is the most that a practical hang glider or paraglider could have before it would limit the occasions that a climb was possible to only when there was strongly rising air.