Creator in Buddhism

[9] Damien Keown notes that in the Saṃyutta Nikāya, the Buddha sees the cycle of rebirths as stretching back "many hundreds of thousands of aeons without discernible beginning.

[12] According to Hayes, in the Tevijja Sutta (DN 13), there is an account of a dispute between two brahmins about how best to reach union with Brahma (Brahmasahavyata), who is seen as the highest god over whom no other being has mastery and who sees all.

"[14] Narada Thera also notes that the Buddha specifically calls out the doctrine of creation by a supreme deity (termed Ishvara) for criticism in the Aṅguttara Nikāya.

[18] In Buddhist suttas, such as DN 1, Mahabrahma forgets his past lives and falsely believes himself to be the Creator, Maker, All-seeing, the Lord.

In this sutta, the Buddha displays his superior knowledge by explaining how a high god named Baka Brahma, who believes himself to be supremely powerful, actually does not know of certain spiritual realms.

As noted by Michael D. Nichols, MN 49 seems to show that "belief in an eternal creator figure is a devious ploy put forward by the Evil One to mislead humanity, and the implication is that Brahmins who believe in the power and permanence of Brahma have fallen for it.

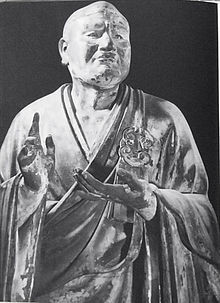

[5] In the Twelve Gate Treatise (十二門論, Shih-erh-men-lun), the Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna (c. 1st–2nd century) works to refute the belief of certain Indian non-Buddhists in a god called Isvara, who is "the creator, ruler and destroyer of the world".

[30] He states (AKB, chapter 2): The universe does not originate from one single cause (ekaṃ kāraṇam) which may be called God/Supreme Lord (Īśvara), Self (Puruṣa), Primal Source (Pradhāna) or any other name.

"[32] Furthermore, the Buddhist also adds: Besides, do you say that God finds joy in seeing the creatures which he has created in the prey of all the distress of existence, including the tortures of the hells?

The profane stanza expresses it well: "One calls him Rudra because he burns, because he is sharp, fierce, redoubtable, an eater of flesh, blood and marrow.

Other doctrines claim that there is a great Brahma, a Time, a Space, a Starting Point, a Nature, an Ether, a Self, etc., that is eternal and really exists, is endowed with all powers, and is able to produce all dharmas.

[36] The 7th-century Buddhist scholar Dharmakīrti advances a number of arguments against the existence of a creator god in his Pramāṇavārtika, following in the footsteps of Vasubandhu.

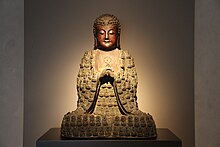

[41][42] Mahayana Buddhist interpretations of the Buddha as a supreme being, which is eternal, all-compassionate, and existing on a cosmic scale, have been compared to theism by various scholars.

For example, Guang Xing describes the Mahayana Buddha as an omnipotent and almighty divinity "endowed with numerous supernatural attributes and qualities".

[43] In Mahayana, a fully awakened Buddha (such as Amitābha) is held to be omniscient as well as having other qualities, such as infinite wisdom, an immeasurable life, and boundless compassion.

[46] Various authors, such as F. Sueki, Douglas Duckworth, and Fabio Rambelli, have described Mahayana Buddhist views using the term "pantheism" (the belief that God and the universe are identical).

[66] The Shingon Buddhist view of the Supreme Buddha Mahāvairocana, whose body is seen as being the whole universe, has also been called "cosmotheism" (the idea that the cosmos is God) by scholars like Charles Eliot, Hajime Nakamura, and Masaharu Anesaki.

[70] B. Alan Wallace writes on how the Tibetan Buddhist Vajrayana concept of the primordial Buddha (Adi-Buddha) is sometimes seen as forming the foundation of both saṃsāra (the world of suffering) and nirvana (liberation).

[72] Douglas Duckworth sees Tibetan tantric Buddhism as "pantheist to the core", since "in its most profound expressions (e.g., highest Yoga tantra), all dualities between the divine and the world are radically undone".

"[73] Eva K. Neumaier-Dargyay notes that the Dzogchen tantra called the Kunjed Gyalpo ("all-creating king") uses symbolic language for the Adi-Buddha Samantabhadra, which is reminiscent of theism.

[29] Neumaier-Dargyay considers the Kunjed Gyalpo to contain theistic-sounding language, such as positing a single "cause of all that exists" (including all Buddhas).

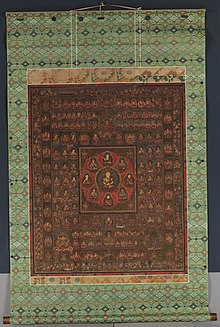

[51] Alexander Studholme also points to how the Kāraṇḍavyūhasūtra presents the great bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara as a kind of supreme lord of the cosmos and as the progenitor of various heavenly bodies and divinities (such as the Sun and Moon, the deities Shiva and Vishnu, etc.

)[74] Avalokiteśvara himself is seen, in the versified version of the sutra, to be an emanation of the first Buddha, the Adi-Buddha, who is called svayambhu (self-existent, not born from anything or anyone) and the "primordial lord" (Adinatha).

[75] The 14th Dalai Lama sees this deity (called Samantabhadra) as a symbol for ultimate reality, "the realm of the Dharmakaya – the space of emptiness".

[52] This doctrine of an "ultimate source", says the Dalai Lama, seems close to the notion of a Creator, since all phenomena, whether they belong to samsara or nirvana, originate therein".

[77] Norbu explains that the Dzogchen idea of the Adi-Buddha Samantabhadra "should be mainly understood as a metaphor to enable us to discover our real condition".

The earliest Christian attempts to refute Buddhism and criticize its teachings were those of Jesuits like Alessandro Valignano, Michele Ruggieri, and Matteo Ricci.

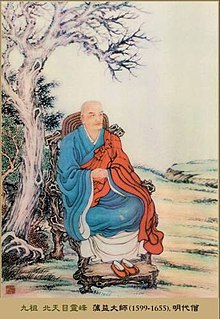

[81] The monk Ouyi Zhixu (蕅益智旭, 1599–1655) later wrote the Bixie ji ("Collected Essays Refuting Heterodoxy"), which specifically attacks Christianity on the grounds of theodicy as well as relying on classical Confucian ethics.

According to Beverley Foulks, in his essays, Zhixu "objects to the way Jesuits invest God with qualities of love, hatred, and the power to punish.

Fukansai Habian (1565–1621) is perhaps one of the best-known of these critics, especially because he was a convert to Christianity who then became an apostate and wrote an anti-Christian polemic, titled Deus Destroyed (Ha Daiusu), in 1620.