Sorcery (goetia)

They cover crafting magical objects, casting spells, performing divination, and summoning supernatural entities, such as angels, spirits, deities, and demons.

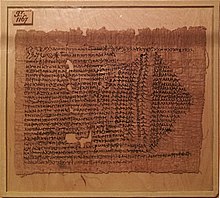

The magical system of ancient Egypt, deified in the form of the god Heka, underwent changes after the Macedonian invasion led by Alexander the Great.

The rise of the Coptic writing system and the Library of Alexandria further influenced the development of magical texts, which evolved from simple charms to encompass various aspects of life, including financial success and fulfillment.

Contemporary practitioners of occultism and esotericism continue to engage with Goetia, drawing from historical texts while adapting rituals to align with personal beliefs.

[3] While the term grimoire is originally European—and many Europeans throughout history, particularly ceremonial magicians and cunning folk, have used grimoires—the historian Owen Davies has noted that similar books can be found all around the world, ranging from Jamaica to Sumatra.

[5] The earliest known written magical incantations come from ancient Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), where they have been found inscribed on cuneiform clay tablets that archaeologists excavated from the city of Uruk and dated to between the 5th and 4th centuries BC.

This likely had an influence upon books of magic, with the trend on known incantations switching from simple health and protection charms to more specific things, such as financial success and sexual fulfillment.

The 1st-century Romano-Jewish historian Josephus mentioned a book circulating under the name of Solomon that contained incantations for summoning demons and described how a Jew called Eleazar used it to cure cases of possession.

The work tells of the building of The Temple and relates that construction was hampered by demons until the archangel Michael gave the King a magical ring.

The New Testament records that after the unsuccessful exorcism by the seven sons of Sceva became known, many converts decided to burn their own magic and pagan books in the city of Ephesus; this advice was adopted on a large scale after the Christian ascent to power.

[14] During the late sixth and early fifth centuries BC, the Persian maguš was Graecicized and introduced into the ancient Greek language as μάγος and μαγεία.

[15] In doing so it transformed meaning, gaining negative connotations, with the magos being regarded as a charlatan whose ritual practices were fraudulent, strange, unconventional, and dangerous.

[24] These qualities, and their perceived deviation from inherently mutable cultural constructs of normality, most clearly delineate ancient magic from the religious rituals of which they form a part.

[26] They contain early instances of: In the first century BC, the Greek concept of the magos was adopted into Latin and used by a number of ancient Roman writers as magus and magia.

In Roman Britain, some fifty dedications to the Mothers are recorded in stone inscriptions and other objects, constituting ample evidence of the importance of the cult among native Celts and others.

[38] Over 80 similar tablets have been discovered in and about the remains of a temple to Mercury nearby, at West Hill, Uley,[39] making south-western Britain one of the major centres for finds of Latin defixiones.

[45] Scholars have found medieval Sator-based charms, remedies, and cures, for a diverse range of applications from childbirth, to toothaches, to love potions, to ways of warding off evil spells, and even to determine whether someone was a witch.

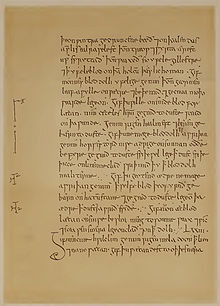

[48] Godfrid Storms argued that animism played a significant role in the worldview of Anglo-Saxon magic, noting that in the recorded charms, "All sorts of phenomenon are ascribed to the visible or invisible intervention of good or evil spirits.

"[49] The primary creature of the spirit world that appear in the Anglo-Saxon charms is the ælf (nominative plural ylfe, "elf"), an entity who was believed to cause sickness in humans.

[50] Another type of spirit creature, a demonic one, believed to cause physical harm in the Anglo-Saxon world was the dweorg or dƿeorg/dwerg ("dwarf"), whom Storms characterised as a "disease-spirit".

[61] It was only beginning in the 1150s that the Church turned its attention to defining the possible roles of spirits and demons, especially with respect to their sexuality and in connection with the various forms of magic which were then believed to exist.

[62] Medieval Europe saw the Latin legal term maleficium[63] applied to forms of sorcery or witchcraft that were conducted with the intention of causing harm.

[65][66] Maleficium was defined as "the practice of malevolent magic, derived from casting lots as a means of divining the future in the ancient Mediterranean world",[67] or as "an act of witchcraft performed with the intention of causing damage or injury; the resultant harm.

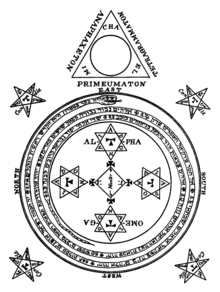

[70] One well-known goetic grimoire is the Ars Goetia, included in the 16th-century text known as The Lesser Key of Solomon,[2] which was likely compiled from materials several centuries older.

[a][73][75] The later Middle Ages saw words for these practitioners of harmful magical acts appear in various European languages: sorcière in French, Hexe in German, strega in Italian, and bruja in Spanish.

[79][80][81] Probably the best-known characteristic of a sorcerer or witch is their ability to cast a spell—a set of words, a formula or verse, a ritual, or a combination of these, employed to do magic.

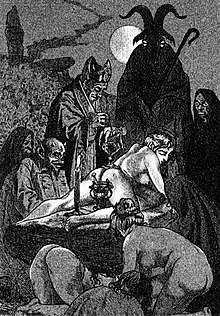

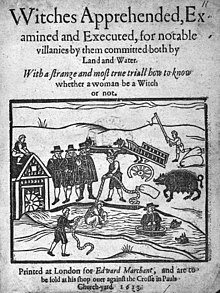

Among the Catholics, Protestants, and secular leadership of the European Early Modern period, fears about sorcery and witchcraft rose to fever pitch and sometimes led to large-scale witch-hunts.

The key century was the fifteenth, which saw a dramatic rise in awareness and terror of witchcraft, culminating in the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum but prepared by such fanatical popular preachers as Bernardino of Siena.

[91] In 1597, King James VI and I published a treatise, Daemonologie, a philosophical dissertation on contemporary necromancy and the historical relationships between the various methods of divination used from ancient black magic.

These individuals draw from historical grimoires, including the classic Lesser Key of Solomon, while also interpreting and adapting its rituals to align with their personal beliefs and spiritual goals.