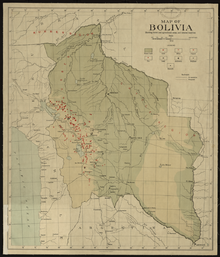

Mining in Bolivia

Colonial era silver mining in Bolivia, particularly in Potosí, played a critical role in the Spanish Empire and the global economy.

[1] Spurred by a massive increase in gold production, however, the mining sector rebounded in 1988, returning to the top of the nation's list of foreign exchange earners.

The twenty-first century has seen a recovery and expansion of the mining sector, and the government of Evo Morales has re-nationalized several facilities.

However, as of 2010[update] mining in Bolivia is primarily in private hands, while the vast majority of miners work in cooperatives.

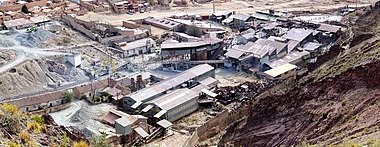

[citation needed] (fine metric tons) (millions of US$) (fine metric tons) (millions of US$) Corporación Minera de Bolivia (Comibol), created in 1952 by the nationalization of the country's tin mines, was a huge multi-mineral corporation controlled by organized labor and the second largest tin enterprise in the world, until it was decentralized into five semi-autonomous mining enterprises in 1986.

[1] In addition to operating twenty-one mining companies, several spare-parts factories, various electricity plants, farms, a railroad, and other agencies, Comibol also provided schooling for over 60,000 children, housing for mining families, health clinics, and popular subsidized commissaries called pulperías.

[1] The government of Evo Morales re-nationalized the cooperative mines at Huanuni (in 2007)[4] and the smelting facilities in Vinto (in February 2007) and Karachipampa (in January 2011).

[1] Beginning in 1987, small miners no longer had to sell their exports through Bamin, a policy shift that boosted that group's output and foreign sales.

[1] Although long among the world's leading tin producers and exporters, the industry faced numerous and complicated structural problems by the early 1980s: the highest cost underground mines and smelters in the world; inaccessibility of the ores because of high altitudes and poor infrastructure; narrow, deep veins found in hard rock; complex tin ores that had to be specially processed to extract tin, antimony, lead, and other ores; depletion of high-grade ores; almost continual labor unrest; deplorable conditions for miners; extensive mineral theft or juqueo; poor macroeconomic conditions; lack of foreign exchange for needed imports; unclear mining policies; few export incentives; and decreasing international demand for tin.

[1] In the late 1980s, however, tin still accounted for a third of all Bolivian mineral exports because of the strong performance by the medium and small mining sectors.

[1] The largest tin-mining company in the private sector was Estalsa Boliviana, which dredged alluvial tin deposits in the Antequera River in northeastern Potosí Department.

[1] Eighty percent of all exports went to the European Economic Community and the United States, with the balance going to various Latin American countries and Czechoslovakia.

[1] Government policies since the early 1970s had sought to expand the percentage of metallic or refined tin exports that offered greater returns.

[1] During the presidency of Evo Morales, Bolivia increased government control over and investment in the tin sector.

[4] The government also nationalized the Vinto smelter citing issues of corruption by private owner Glencore in February 2007.

[4] The still-unopened Karachipampa was nationalized in 2011 following the regional protest in Potosí's demand for its operation and the failure of foreign investors to accomplish this.

In July 2011, the Chinese firm Vicstar Union Engineering (a joint venture of Shenzhen Vicstar Import and Export Co. and Yantai Design and Research Engineering Co. Ltd of the Shandong Gold Group) won a contract to build a new smelter for Comibol at Huanuni.

[1] With the collapse of tin, the government was increasingly interested in exploiting its large reserves of other minerals, particularly silver and zinc.

[1] Antimony, a strategic mineral used in flameproofing compounds and semiconductors, was exported in concentrates, trioxides, and alloys to all regions of the world, with most sales going to Britain and Brazil.

[1] But the dramatic decline in tungsten prices in the 1980s severely hurt production, despite the fact that reserves stood at 60,000 tons.

[1] A large percentage of the cooperatives worked in Tipuani, Guanay, Mapiri, Huayti, and Teoponte in a 21,000-hectare region set aside for gold digging and located 120 kilometers north of La Paz.

[1] A few medium-sized mining operations, as well as the Armed Forces National Development Corporation (Corporación de las Fuerzas Armadas para el Desarrollo Nacional—Cofadena) became involved in the gold rush in the 1980s.

[1] Government policy favored augmenting gold reserves as a means of leveraging more external finance for development projects.

[1][3] According to the United States Geological Survey, Bolivia’s resources of lithium are estimated to be 9 million metric tons as of 2018.

[1] Widely criticized for its overcapacity,[1] the plant suffered continual delays due to insufficient ore inputs and lack of investment.

[18] As of May 2011[update], Comibol promises to begin its operation in November; one-quarter of the production at the San Cristóbal mine is pledged as input to the facility.