Goldbach's conjecture

On 7 June 1742, the Prussian mathematician Christian Goldbach wrote a letter to Leonhard Euler (letter XLIII),[2] in which he proposed the following conjecture: Goldbach was following the now-abandoned convention of considering 1 to be a prime number,[3] so that a sum of units would be a sum of primes.

Every integer greater than 2 can be written as the sum of three primes.Euler replied in a letter dated 30 June 1742[5] and reminded Goldbach of an earlier conversation they had had ("... so Ew vormals mit mir communicirt haben ..."), in which Goldbach had remarked that the first of those two conjectures would follow from the statement This is in fact equivalent to his second, marginal conjecture.

In the letter dated 30 June 1742, Euler stated:[6][7] Dass ... ein jeder numerus par eine summa duorum primorum sey, halte ich für ein ganz gewisses theorema, ungeachtet ich dasselbe nicht demonstriren kann.That ... every even integer is a sum of two primes, I regard as a completely certain theorem, although I cannot prove it.René Descartes wrote that "Every even number can be expressed as the sum of at most three primes.

This result was subsequently enhanced by many authors, such as Olivier Ramaré, who in 1995 showed that every even number n ≥ 4 is in fact the sum of at most 6 primes.

The best known result currently stems from the proof of the weak Goldbach conjecture by Harald Helfgott,[15] which directly implies that every even number n ≥ 4 is the sum of at most 4 primes.

In 1951, Yuri Linnik proved the existence of a constant K such that every sufficiently large even number is the sum of two primes and at most K powers of 2.

[22] A proof for the weak conjecture was submitted in 2013 by Harald Helfgott to Annals of Mathematics Studies series.

However, the converse implication and thus the strong Goldbach conjecture would remain unproven if Helfgott's proof is correct.

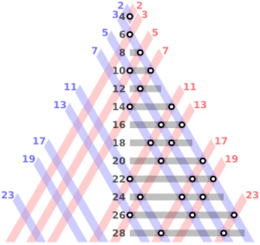

If one pursues this heuristic, one might expect the total number of ways to write a large even integer n as the sum of two odd primes to be roughly Since ln n ≪ √n, this quantity goes to infinity as n increases, and one would expect that every large even integer has not just one representation as the sum of two primes, but in fact very many such representations.

Pursuing this type of analysis more carefully, G. H. Hardy and John Edensor Littlewood in 1923 conjectured (as part of their Hardy–Littlewood prime tuple conjecture) that for any fixed c ≥ 2, the number of representations of a large integer n as the sum of c primes n = p1 + ⋯ + pc with p1 ≤ ⋯ ≤ pc should be asymptotically equal to where the product is over all primes p, and γc,p(n) is the number of solutions to the equation n = q1 + ⋯ + qc mod p in modular arithmetic, subject to the constraints q1, …, qc ≠ 0 mod p. This formula has been rigorously proven to be asymptotically valid for c ≥ 3 from the work of Ivan Matveevich Vinogradov, but is still only a conjecture when c = 2.

[citation needed] In the latter case, the above formula simplifies to 0 when n is odd, and to when n is even, where Π2 is Hardy–Littlewood's twin prime constant This is sometimes known as the extended Goldbach conjecture.

[37] The connection is made through the Busy Beaver function, where BB(n) is the maximum number of steps taken by any n state Turing machine that halts.

Hence if BB(27) was known, and the Turing machine did not stop in that number of steps, it would be known to run forever and hence no counterexamples exist (which proves the conjecture true).