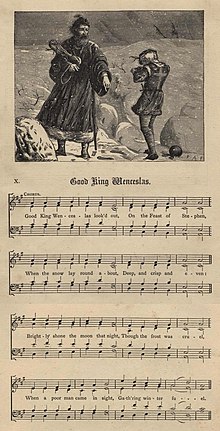

Good King Wenceslas

In 1853, English hymnwriter John Mason Neale wrote the lyrics in collaboration with his music editor Thomas Helmore to fit the melody of the 13th-century spring carol "Tempus adest floridum" ("Eastertime Is Come"), which they had found in the 1582 Finnish song collection Piae Cantiones.

[7] Referring approvingly to these hagiographies, a preacher from the 12th century wrote:[8][9] But his deeds I think you know better than I could tell you; for, as is read in his Passion, no one doubts that, rising every night from his noble bed, with bare feet and only one chamberlain, he went around to God's churches and gave alms generously to widows, orphans, those in prison and afflicted by every difficulty, so much so that he was considered, not a prince, but the father of all the wretched.Several centuries later the legend was claimed as fact by Pope Pius II,[10] who himself also walked ten miles barefoot in the ice and snow as an act of pious thanksgiving.

[12] The usual English spelling of Duke Wenceslas's name, Wenceslaus, is occasionally encountered in later textual variants of the carol, although it was not used by Neale in his version.

The tune is that of "Tempus adest floridum" ("Eastertime has come"), a 13th-century spring carol in 76 76 Doubled Trochaic metre, first published in the Finnish song book Piae Cantiones in 1582.

Piae Cantiones is a collection of seventy-four songs compiled by Jacobus Finno, the Protestant headmaster of Turku Cathedral School, and published by Theodoric Petri, a young Catholic printer.

[14] A text beginning substantially the same as the 1582 "Piae" version is also found in the German manuscript collection Carmina Burana as CB 142, where it is substantially more carnal; CB 142 has clerics and virgins playing the "game of Venus" (goddess of love) in the meadows, while in the Piae version they are praising the Lord from the bottom of their hearts.

As a member of the Tractarian Oxford Movement, Neale was interested in restoring Catholic ceremony, saints days, and music back into the Anglican church.

In 1849 he had published Deeds of Faith: Stories for Children from Church History which recounted legends from Christian tradition in Romantic prose.

(In the English tradition, two-syllable rhymes are generally associated with light or comic verse, which may be part of the reason some critics have demeaned Neale's lyrics as "doggerel".)

Unfortunately Neale in 1853 substituted for the Spring carol this 'Good King Wenceslas', one of his less happy pieces, which E. Duncan goes so far as to call 'doggerel', and Bullen condemns as 'poor and commonplace to the last degree'.

not without hope that, with the present wealth of carols for Christmas, 'Good King Wenceslas' may gradually pass into disuse, and the tune be restored to spring-time.

She goes on to say that Neale's "ponderous moral doggerel" does not fit the lighthearted dance measure of the original tune, and that if performed in the correct manner it "sounds ridiculous to pseudo-religious words".

"[26] Jeremy Summerly and Nicolas Bell of the British Museum also strongly rebut Dearmer's 20th century criticism, noting: "it could have been awful, but it isn't, it's magical .