Parable of the Good Samaritan

Some Christians, such as Augustine, have interpreted the parable allegorically, with the Samaritan representing Jesus Christ, who saves the sinful soul.

In the Gospel of Luke chapter 10, the parable is introduced by a question, known as the Great Commandment: Behold, a certain lawyer stood up and tested him, saying, "Teacher, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?"

[8] Tensions between them were particularly high in the early decades of the 1st century because Samaritans had desecrated the Jewish Temple at Passover with human bones.

[11] Or, on another, more positive note, it may indicate that the lawyer has recognized that both his questions have been answered and now concludes by generally expressing that anyone behaving thus is a (Leviticus 19:18)[12] "neighbor" eligible to inherit eternal life.

Today, to remedy this missing context, the story is often recast in a more modern setting where the people are ones in equivalent social groups known not to interact comfortably.

[17] Klyne Snodgrass wrote: "On the basis of this parable we must deal with our own racism but must also seek justice for, and offer assistance to, those in need, regardless of the group to which they belong.

[9] On the other hand, the depiction of travel downhill (from Jerusalem to Jericho) may indicate that their temple duties had already been completed, making this explanation less likely,[28] although this is disputed.

And the fact that the Samaritan promises he will return represents the Savior's second coming.John Welch further states: This allegorical reading was taught not only by ancient followers of Jesus, but it was virtually universal throughout early Christianity, being advocated by Irenaeus, Clement, and Origen, and in the fourth and fifth centuries by Chrysostom in Constantinople, Ambrose in Milan, and Augustine in North Africa.

[32] John Calvin was not impressed by Origen's allegorical reading: The allegory which is here contrived by the advocates of free will is too absurd to deserve refutation.

According to them, under the figure of a wounded man is described the condition of Adam after the fall; from which they infer that the power of acting well was not wholly extinguished in him; because he is said to be only half-dead.

For example, G. B. Caird wrote: Dodd quotes as a cautionary example Augustine's allegorisation of the Good Samaritan, in which the man is Adam, Jerusalem the heavenly city, Jericho the moon – the symbol of immortality; the thieves are the devil and his angels, who strip the man of immortality by persuading him to sin and so leave him (spiritually) half dead; the priest and Levite represent the Old Testament, the Samaritan Christ, the beast his flesh which he assumed at the Incarnation; the inn is the church and the innkeeper the apostle Paul.

By leaving aside the identity of the wounded man and by portraying the Samaritan traveler as one who performs the law (and so as one whose actions are consistent with an orientation to eternal life), Jesus has nullified the worldview that gives rise to such questions as, Who is my neighbor?

"[42] Martin Luther King Jr. often spoke of this parable, contrasting the rapacious philosophy of the robbers, and the self-preserving non-involvement of the priest and Levite, with the Samaritan's coming to the aid of the man in need.

One day we must come to see that the whole Jericho road must be transformed so that men and women will not be constantly beaten and robbed as they make their journey on life's highway.

It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.Thomas Aquinas states that there are three points to be noted in this parable: Firstly, the manifold misery of sinners: "A certain man went down from Jerusalem."

"[44] Justus Knecht gives the deeper interpretation of this parable, according to the Church Fathers, writing: Jesus Himself is the Good Samaritan, as proved by His treatment of the robbed and wounded human race.

Neither priest nor Levite, i. e. neither sacrifice nor law of the Old Covenant, could help him, or heal his wounds; they only made him realize more fully his helpless condition.

When He left this earth to return to heaven, He gave to the guardians of His Church the twofold treasure of His doctrine and His grace, and ordered them to tend the still weak man, until He Himself came back to reward every one according to his works.

If "Samaritan" has been substituted by the anti-Judean gospel-writer for the original "Israelite", no reflection was intended by Jesus upon Jewish teaching concerning the meaning of neighbor; and the lesson implied is that he who is in need must be the object of love.

234, 302) that "'Love thy neighbor as thyself' is a command of all-embracing love, and is a fundamental principle of the Jewish religion"; and Stade 1888, p. 510a, when charging with imposture the rabbis who made this declaration, is entirely in error.

The twist between the lawyer's question and Jesus' answer is entirely in keeping with Jesus' radical stance: he was making the lawyer rethink his presuppositions.The unexpected appearance of the Samaritan led Joseph Halévy to suggest that the parable originally involved "a priest, a Levite, and an Israelite",[53] in line with contemporary Jewish stories, and that Luke changed the parable to be more familiar to a gentile audience.

The term "good Samaritan" is used as a common metaphor: "The word now applies to any charitable person, especially one who, like the man in the parable, rescues or helps out a needy stranger.

[64] In some Eastern Orthodox icons of the parable, the identification of the Good Samaritan as Christ is made explicit with a halo bearing a cross.

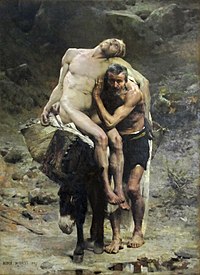

[65] The numerous later artistic depictions of the parable include those of Rembrandt, Jan Wijnants, Vincent van Gogh, Aimé Morot, Domenico Fetti, Johann Carl Loth, George Frederic Watts, and Giacomo Conti.

In his essay Lost in Non-Translation, biochemist and author Isaac Asimov argues that to the Jews of the time there were no good Samaritans; in his view, this was half the point of the parable.

As Asimov put it, we need to think of the story occurring in Alabama in 1950, with a mayor and a preacher ignoring a man who has been beaten and robbed, with the role of the Samaritan being played by a poor black sharecropper.

[67] Australian poet Henry Lawson wrote a poem on the parable ("The Good Samaritan"), of which the third stanza reads: He's been a fool, perhaps, and would Have prospered had he tried, But he was one who never could Pass by the other side.

His resulting work for solo voices, choir, and orchestra, Cantata Misericordium, sets a Latin text by Patrick Wilkinson that tells the parable of the Good Samaritan.

In a real-life psychology experiment sometime before 1973, a number of seminary students – in a rush to teach on this parable – failed to stop to help a shabbily dressed person on the side of the road.

[70] In the English law of negligence, when establishing a duty of care in Donoghue v Stevenson Lord Atkin applied the neighbour principle—drawing inspiration from the Biblical Golden Rule[72] as in the parable of the Good Samaritan.