Gospel of Thomas

Scholars speculate the works were buried in response to a letter from Bishop Athanasius declaring a strict canon of Christian scripture.

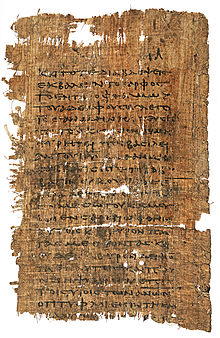

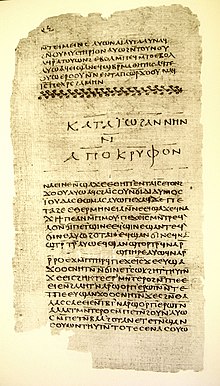

[7][8][9] The Coptic-language text, the second of seven contained in what scholars have designated as Nag Hammadi Codex II, is composed of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus.

[16] Because of its discovery with the Nag Hammadi library, and the cryptic nature, it was widely thought the document originated within a school of early Christians, proto-Gnostics.

This fact, along with the quite different wording Hippolytus uses when apparently quoting it (see below), suggests that the Gospel of Thomas "may have circulated in more than one form and passed through several stages of redaction.

The earliest surviving written references to the Gospel of Thomas are found in the writings of Hippolytus of Rome (c. 222–235) and Origen of Alexandria (c. 233).

[31] Hippolytus wrote in his Refutation of All Heresies 5.7.20: [The Naassenes] speak [...] of a nature which is both hidden and revealed at the same time and which they call the thought-for kingdom of heaven which is in a human being.

They transmit a tradition concerning this in the Gospel entitled "According to Thomas," which states expressly, "The one who seeks me will find me in children of seven years and older, for there, hidden in the fourteenth aeon, I am revealed.

[5] Valantasis and other scholars argue that it is difficult to date Thomas because, as a collection of logia without a narrative framework, individual sayings could have been added to it gradually over time.

[43] Marvin Meyer also asserted that the genre of a "sayings collection" is indicative of the 1st century,[44] and that in particular the "use of parables without allegorical amplification" seems to antedate the canonical gospels.

[49] In the few instances where the version in Thomas seems to be dependent on the synoptics, Koester suggests, this may be due to the influence of the person who translated the text from Greek into Coptic.

With respect to the famous story of "Doubting Thomas",[56] it is suggested[52] that the author of John may have been denigrating or ridiculing a rival school of thought.

[note 2] John portrays Thomas as physically touching the risen Jesus, inserting fingers and hands into his body, and ending with a shout.

As this scholarly debate continued, theologian Christopher W. Skinner disagreed with Riley, DeConick, and Pagels over any possible John–Thomas interplay, and concluded that in the book of John, Thomas the disciple "is merely one stitch in a wider literary pattern where uncomprehending characters serve as foils for Jesus's words and deeds.

"[59] Albert Hogeterp argues that the Gospel's saying 12, which attributes leadership of the community to James the Just rather than to Peter, agrees with the description of the early Jerusalem church by Paul in Galatians 2:1–14[60] and may reflect a tradition predating 70 AD.

Patterson argues that this can be interpreted as a criticism against the school of Christianity associated with the Gospel of Matthew, and that "[t]his sort of rivalry seems more at home in the first century than later", when all the apostles had become revered figures.

[63] According to Meyer, Thomas's saying 17 – "I shall give you what no eye has seen, what no ear has heard and no hand has touched, and what has not come into the human heart" – is strikingly similar to what Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 2:9,[64][44] which was itself an allusion to Isaiah 64:4.

[68] In this case it has been suggested that the dependence is best explained by the author of Thomas making use of an earlier harmonised oral tradition based on Matthew and Luke.

[69][70] Biblical scholar Craig A. Evans also subscribes to this view and notes that "Over half of the New Testament writings are quoted, paralleled, or alluded to in Thomas...

[81] Klyne Snodgrass notes that saying 65–66 of Thomas containing the Parable of the Wicked Tenants appears to be dependent on the early harmonisation of Mark and Luke found in the old Syriac gospels.

The Gospel of Thomas proclaims that the Kingdom of God is already present for those who understand the secret message of Jesus (saying 113), and lacks apocalyptic themes.

Additionally, the Gospel of Thomas conveys that Jesus ridiculed those who thought of the Kingdom of God in literal terms, as if it were a specific place.

Wright's reasoning for this dating is that the "narrative framework" of 1st-century Judaism and the New Testament is radically different from the worldview expressed in the sayings collected in the Gospel of Thomas.

"The Thomas Christians are told the truth about their divine origins, and given the secret passwords that will prove effective in the return journey to their heavenly home."

This is, obviously, the non-historical story of Gnosticism [...] It is simply the case that, on good historical grounds, it is far more likely that the book represents a radical translation, and indeed subversion, of first-century Christianity into a quite different sort of religion, than that it represents the original of which the longer gospels are distortions [...] Thomas reflects a symbolic universe, and a worldview, which are radically different from those of the early Judaism and Christianity.

Bible scholar Bruce Metzger wrote regarding the formation of the New Testament canon: Although the fringes of the emerging canon remained unsettled for generations, a high degree of unanimity concerning the greater part of the New Testament was attained among the very diverse and scattered congregations of believers not only throughout the Mediterranean world, but also over an area extending from Britain to Mesopotamia.

[97] Considered by some as one of the earliest accounts of the teachings of Jesus, the Gospel of Thomas is regarded by some scholars as one of the most important texts in understanding early Christianity outside the New Testament.

J. Menard produced a summary of the academic consensus in the mid-1970s that stated that the gospel was probably a very late text written by a Gnostic author, thus having very little relevance to the study of the early development of Christianity.

"[105] The mysticism of the Gospel of Thomas also lacks many themes found in second century Gnosticism,[106] including any allusion to a fallen Sophia or an evil Demiurge.

[98][109] Scholars may utilize one of several critical tools in biblical scholarship, the criterion of multiple attestation, to help build cases for historical reliability of the sayings of Jesus.

[116][117] Jorunn Jacobsen Buckley argued that Logion 114 represents a process with females becoming male before achieving the prelapsarian state, a reversal of the Genesis story in which women were made from men.