Gothic Line

To downgrade its importance in the eyes of both friend and foe, he ordered the name, with its historic connotations, changed, reasoning that if the Allies managed to break through they would not be able to use the more impressive name to magnify their victory claims.

Using more than 15,000 slave labourers, the Germans created more than 2,000 well-fortified machine gun nests, casemates, bunkers, observation posts and artillery fighting positions to repel any attempt to breach the Gothic Line.

[1] Initially, this line was breached during Operation Olive (also sometimes known as the Battle of Rimini), but Kesselring's forces were consistently able to retire in good order.

This continued to be the case up to March 1945, with the Gothic Line being breached but with no decisive breakthrough; this would not take place until April 1945 during the final Allied offensive of the Italian Campaign.

After the nearly concurrent breakthroughs at Cassino and Anzio in spring 1944, the 11 nations representing the Allies in Italy finally had a chance to trap the Germans in a pincer movement and to realize some of the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill's strategic goals for the long, costly campaign against the Axis "underbelly".

One of his colleagues who ignored this caution—Wilhelm Crisolli (commanding the 20th Luftwaffe Field Division)—was caught and killed by partisans as he returned from a conference at corps headquarters.

Nevertheless, prior to the Allies' attack, Kesselring had declared himself satisfied with the work done, especially on the Adriatic side where he "...contemplated an assault on the left wing....with a certain confidence".

Nevertheless, Winston Churchill and the British Chiefs of Staff were keen to break through the German defences to open up the route to the northeast through the "Ljubljana Gap" into Austria and Hungary.

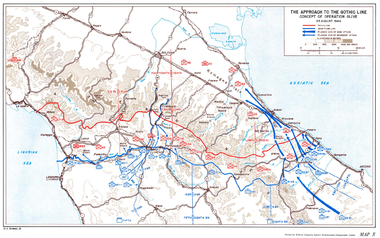

Operation Olive—as the new offensive was christened—called for Leese's Eighth Army to attack up the Adriatic coast toward Pesaro and Rimini and draw in the German reserves from the centre of the country.

The left flank of the Eighth Army front was guarded by British X Corps employing the 10th Indian Infantry Division and two armoured car regiments, 12th and 27th Lancers.

By 30 August, the Canadian and British Corps had reached the Green I main defensive positions running along the ridges on the far side of the Foglia river.

Taking advantage of the Germans' lack of manpower, the Canadians punched through and by 3 September had advanced a further 15 mi (24 km) to the Green II line of defences running from the coast near Riccione.

However, LXXVI Panzer Corps on the German 10th Army's left wing had withdrawn in good order behind the line of the Conca river.

[19] Fierce resistance from the Corps′ 1st Parachute Division—commanded by Heidrich (supported by intense artillery fire from the Coriano ridge in the hills on the Canadians' left)—brought their advance to a halt.

On 3–4 September, while the Canadians once again attacked along the coastal plain, V Corps made an armoured thrust to dislodge the Coriano Ridge defences and reach the Marano river.

Once again movement ground to a crawl, and the German defenders had the opportunity to reorganise and reinforce their positions on the Marano river, and the salient to the Lombardy plain closed.

During the night of 19/20 September, Brigadier Richard W. Goodbody, commanding the 2nd Armoured Brigade, ordered (with many doubts) the 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen's Bays) to attack Pt 153 at 10.50.

Fortunately for the 9th Queen's Royal Lancers, who had been ordered to pass through the Bays, their attack was postponed after strong representations had been made to higher HQ.

Progress for the Eighth Army became very slow with mud slides caused by the torrential rain making it difficult to keep roads and tracks open, creating a logistical nightmare.

Although they were out of the hills, the plains were waterlogged and the Eighth Army found themselves confronted, as they had the previous autumn, by a succession of swollen rivers running across their line of advance.

The transfer of 356th Infantry Division to the Adriatic weakened the defences around the Il Giogo pass which was already potentially an area of weakness, being on the boundary between 10th and 14th Armies.

Some fierce resistance was met from outposts but at the end of the first week in September, once reorganisation had taken place following the withdrawal of three divisions to reinforce the pressured Adriatic front, the Germans withdrew to the main Gothic Line defences.

Keyes tried to flank the II Giogo Pass by attacking both the peaks of Monticello and Monte Altuzzo using the 91st Infantry Division in a bold attempt to bounce the Germans off the positions, but this failed.

Attacking on 17 September, supported by both American and British artillery, the infantry fought their way onto Monte Pratone, some 2–3 mi (3.2–4.8 km) east of the Il Giogo pass and a key position on the Gothic Line.

By the end of the month, the Brazilian unit had conquered Monte Prano and controlled the Serchio valley region without suffering any major casualties.

In October, it also took Fornaci with its munitions factory, and Barga; while the 370th received reinforcements from other units (365th and 371st), to ensure the Fifth Army left wing sector at the Ligurian Sea.

Between 21 September and 3 October, U.S. 88th Division had fought its way to a standstill on the route to Imola suffering 2,105 men killed and wounded — roughly the same as the whole of the rest of II Corps during the actual breaching of the Gothic Line.

However, as it had on the Adriatic coast, the weather had broken and rain and low cloud prevented air support while the roads back to the ever more distant supply dumps near Florence became morasses.

The situation in the British Eighth Army was even worse: Replacement cadres were being diverted to northern Europe and I Canadian Corps was ordered to prepare to ship to the Netherlands in February of the following year.

[43] During November and December, Fifth Army concentrated on dislodging the Germans from their well-placed artillery positions which had been key in preventing the Allied advance towards Bologna and the Po Valley.