Government of Ireland Act 1920

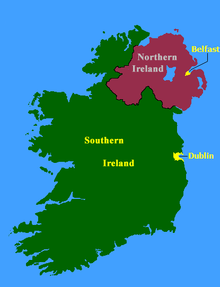

The institutions set up under this Act for Northern Ireland continued to function until they were suspended by the British parliament in 1972 as a consequence of the Troubles.

Various attempts had been made to give Ireland limited regional self-government, known as Home rule, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Because of the continuing threat of civil war in Ireland, King George V called the Buckingham Palace Conference in July 1914 where Irish Nationalist and Unionist leaders failed to reach agreement.

In an attempt at compromise, the British government put forward an amending bill, which would have allowed for Ulster to be temporarily excluded from the working of the Act; this failed to satisfy either side and the stalemate continued until overtaken by the outbreak of World War I.

However, the Suspensory Act 1914 (which received Royal Assent on the same day) meant that implementation would be suspended for the duration of what was expected to be only a short European war.

Sinn Féin, standing for 'an independent sovereign Ireland', won 73 of the 105 parliamentary seats on the island in the 1918 general election.

Dáil Éireann, after a number of meetings, was declared illegal in September 1919 by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Viscount French.

A delay ensued because of the effective end of the First World War in November 1918, the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 and the Treaty of Versailles that was signed in June 1919.

The Bill's second reading debates in late March 1920 revealed that already a large number of Irish members of parliament present felt that the proposals were unworkable.

They preferred that all or most of Ulster would remain fully within the United Kingdom, accepting the proposed northern Home Rule state only as the second best option.

After considerable delays in debating the financial aspects of the measure, the substantive third reading of the Bill was approved by a large majority on 11 November 1920.

On the day of the passing of the Act the MP representing North East Tyrone, Thomas Harbison predicted that violence would result in his constituency: "This is not a Bill for the better government of Ireland.

"[12] A considerable number of the Irish Members present voted against the Bill, including Southern Unionists such as Maurice Dockrell and Nationalists like Joe Devlin.

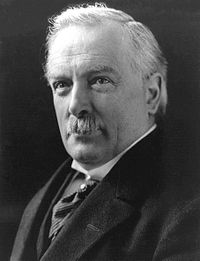

During a speech at Caernarvon (in October 1920) Lloyd George stated his reasoning for reserving specific governmental functions: "The Irish temper is an uncertainty and dangerous forces like armies and navies are better under the control of the Imperial Parliament.

[15] Apparently referring to the results of that election, on 14 December 1921 the British Prime Minister spoke of the coercion of Tyrone and Fermanagh: There is no doubt—certainly since the Act of 1920—that the majority of the people of two counties prefer being with their Southern neighbours to being in the Northern Parliament... What does that mean?

[16] At the apex of the governmental system was to be the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, who would be the Monarch's representative in both of the Irish home rule regions.

Such structures matched the theory in the British dominions, such as Canada and Australia, where in powers belonged to the governor-general and there was no normal responsibility to parliament.

Though it was superseded in large part, its repeal remained a matter of controversy until accomplished in the 1990s (under the provisions of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement).

The Provisional Government of the Irish Free State was constituted on 14 January 1922 "at a meeting of members of the Parliament elected for constituencies in Southern Ireland".

The Council of Ireland never functioned as hoped (as an embryonic all-Ireland parliament), as the new governments decided to find a better mechanism in January 1922.