Grace Hopper

Grace Brewster Hopper (née Murray; December 9, 1906 – January 1, 1992) was an American computer scientist, mathematician, and United States Navy rear admiral.

She left her position at Vassar to join the United States Navy Reserve during World War II.

Hopper began her computing career in 1944 as a member of the Harvard Mark I team, led by Howard H. Aiken.

[2][3][4][5] In 1954, Eckert–Mauchly chose Hopper to lead their department for automatic programming, and she led the release of some of the first compiled languages like FLOW-MATIC.

In 1959, she participated in the CODASYL consortium, helping to create a machine-independent programming language called COBOL, which was based on English words.

Her parents, Walter Fletcher Murray and Mary Campbell Van Horne, were of Scottish and Dutch descent, and attended West End Collegiate Church.

[12] Her great-grandfather, Alexander Wilson Russell, an admiral in the US Navy, fought in the Battle of Mobile Bay during the Civil War.

Grace was initially rejected for early admission to Vassar College at age 16 (because her test scores in Latin were too low), but she was admitted the next year.

In 1934, Hopper earned a Ph.D. in mathematics from Yale[17] under the direction of Øystein Ore.[15][18] Her dissertation, "New Types of Irreducibility Criteria",[19] was published that same year.

She was also denied on the basis that her job as a mathematician and mathematics professor at Vassar College was valuable to the war effort.

[22] During the war in 1943, Hopper obtained a leave of absence from Vassar and was sworn into the United States Navy Reserve; she was one of many women who volunteered to serve in the WAVES.

Hopper graduated first in her class in 1944, and was assigned to the Bureau of Ships Computation Project at Harvard University as a lieutenant, junior grade.

Hopper's request to transfer to the regular Navy at the end of the war was declined due to her advanced age of 38.

[21] Beginning in 1954, Hopper's work was influenced by the Laning and Zierler system, which was the first compiler to accept algebraic notation as input.

[23] In the 1970s, Hopper advocated for the Defense Department to replace large, centralized systems with networks of small, distributed computers.

[26]: 119 She developed the implementation of standards for testing computer systems and components, most significantly for early programming languages such as FORTRAN and COBOL.

The Navy tests for conformance to these standards led to significant convergence among the programming language dialects of the major computer vendors.

In accordance with Navy attrition regulations, Hopper retired from the Naval Reserve with the rank of commander at age 60 at the end of 1966.

She was promoted to captain in 1973 by Admiral Elmo R. Zumwalt Jr.[33] After Republican Representative Philip Crane saw her on a March 1983 segment of 60 Minutes, he championed a joint resolution to promote Hopper to commodore on the retired list; the resolution was referred to, but not reported out of, the Senate Armed Services Committee.

[41] At the time of her retirement, she was the oldest active-duty commissioned officer in the United States Navy (79 years, eight months and five days), and had her retirement ceremony aboard the oldest commissioned ship in the United States Navy (188 years, 9 months, 23 days).

Hopper was initially offered a position by Rita Yavinsky, but she insisted on going through the typical formal interview process.

She then proposed in jest that she would be willing to accept a position which made her available on alternating Thursdays, exhibited at their museum of computing as a pioneer, in exchange for a generous salary and unlimited expense account.

Although no longer a serving officer, she always wore her Navy full dress uniform to these lectures contrary to U.S. Department of Defense policy.

[44] In 2016 Hopper received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor, in recognition of her remarkable contributions to the field of computer science.

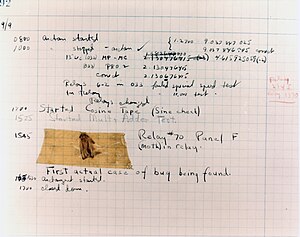

[48][49] The remains of the moth can be found taped into the group's log book at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.[47] Hopper became known for her nanoseconds visual aid.

At many of her talks and visits, she handed out "nanoseconds" to everyone in the audience, contrasting them with a coil of wire 984 feet (300 meters) long,[50] representing a microsecond.

[112] Held yearly, this conference is designed to bring the research and career interests of women in computing to the forefront.