Grant's Tomb

[13] In his will, Grant had indicated that he wished to be interred in St. Louis, Missouri, or Galena, Illinois, where his family owned plots in local cemeteries, or in New York City, where he had lived in his final years.

[21] Grace wrote a letter to prominent New Yorkers on July 24, 1885, to gather support for a national monument in Grant's honor:[18][21] Dear Sir: In order that the City of New York, which is to be the last resting place of General Grant, should initiate a movement to provide for the erection of a National Monument to the memory of the great soldier, and that she should do well and thoroughly her part, I respectfully request you to act as one of a Committee to consider ways and means for raising the quota to be subscribed by the citizens of New York City for this object, and beg that you will attend a meeting to be held at the Mayor's office on Tuesday next, 28 inst., at three o'clock ...[21][22]The preliminary meeting was attended by 85 New Yorkers who established the Committee on Organization.

[30][b] The general public greatly opposed the plans,[31] and the Grant family believed the sites in Central Park were too small to fit both Ulysses and Julia.

[50][51] By mid-August, the city's park commissioners had asked Vaux and engineer William Barclay Parsons to determine the boundaries of a permanent memorial site for Grant's tomb.

[56] Some members of the public claimed the relatively remote site had been selected only to attract tourists and encourage real estate development,[57] although the surrounding area was built up in the 1890s.

[67] Although there was great enthusiasm for a monument to Grant, early fundraising efforts were stifled by growing negative public opinion expressed by out-of-state press.

[68] The opposition was vocal in the view that the monument should be in Washington, D.C.[68] Grace tried to calm the controversy by publicly releasing Julia's justification for the Riverside Park site as the resting place for her husband in October 1885.

[99][100] As fundraising slowed down, people began to lose confidence in the Grant Monument Association,[101] and members of the public offered their own proposals for the memorial.

[105] Although the American Institute of Architects (AIA) recommended that the GMA host a formal architectural design competition, the association ignored this advice[106][107] and did not contact other groups that had built similar monuments.

[114][115] Greener began writing to other groups, such as the Garfield National Monument Association, for advice in early 1887, and he hired Napoleon LeBrun as consulting architect.

[131][132] Some of the plans had been submitted to the American Architect and Building News three years earlier,[132] and about one-third of these entries had intact drawings or illustrations by the late 20th century.

[140] The Grand Army of the Republic had proposed a competing plan for a temple on the site,[141][142] and many out-of-state supported the idea of moving Grant's remains to Arlington National Cemetery.

[179] The next week, the GMA awarded a $18,875 contract to John T. Brady for the foundation's construction,[180][181] and Cornelius Vanderbilt II established a second fund for the Grant Monument.

[222] Duncan and Porter began acquiring 16 million pounds (7,300,000 kg) of granite from New England,[219] and Brady was awarded a $104,482 contract to construct the rest of the structure in early 1893.

[252][253][254] Despite inclement weather,[255][256] the dedication drew an estimated one million spectators,[257][255] as well as more than 50,000 marchers who paraded to the tomb from Madison Square Park 6 miles (9.7 km) to the south.

[283][284][282] The Grant family also donated to the GMA several thousand letters that Ulysses had written,[282] and battle flags were placed in the reliquary rooms at the tomb's northwest and northeast corners in 1903.

[303] The number of visitors was in decline by the 1910s, in part since many Civil War veterans were dying, and many younger Americans were unaware of Grant's importance to previous generations.

[319][335] Workers also installed anti-bird screens,[328] built a plaza around the monument,[335][336] cleaned the interior of the dome, and relocated the curator's office to the southeast corner.

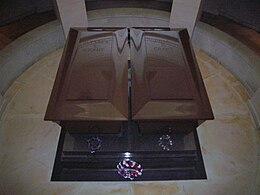

[339] Artists William Mues and Jeno Juszko designed five busts of Union Army generals around the crypt as part of the Federal Art Project.

[347] The GMA first proposed relocating an existing statue in Brooklyn in 1938; although parks commissioner Robert Moses supported this plan,[348][349] residents of the borough heavily opposed it.

[381] After taking over Grant's Tomb, the NPS wanted to add an equestrian statue, install a pediment, modify the roof,[382] and improve pedestrian flow around the memorial.

[426] Newspapers regularly reported on crimes at the tomb in the late 1980s and early 1990s,[425] describing the monument as a frequent site for public urination and defecation, drug use, and muggings.

[480][465] The area near the memorial is served by the M5, M4, and M104 routes of MTA Regional Bus Operations, while the 1 train of the New York City Subway stops at 125th Street and Broadway.

[460] The area north of Grant's Tomb has several ginkgo trees,[486] as well as a Chinese cork, which date from Li Hongzhang's visit to the United States in 1897.

Early plans for Grant's Tomb called for the installation of equestrian statues, depicting generals who led the Union Army, on each stone block.

[310] At the center of the base's southern elevation, above the portico, is a plaque with the inscription "Let us have peace", referring to Grant's acceptance statement after the Republican Party nominated him as its candidate for the 1868 United States presidential election.

[535] The Builder magazine similarly took issue with the scale of the exterior, and it described the "motif of the interior" as plainer than that of Les Invalides, but still wrote that "it is entitled to rank among the most notable monuments in America".

[413] Of the monument itself, the WPA Guide to New York City wrote in 1939: "The high conical roof slopes downward to a circular colonnade atop the cube of the main hall; the difficult problem of uniting the three forms harmoniously remains unsolved.

[477] The same year, an author for The Record of New Jersey wrote that "chances are you can't think of anyone—not even your rich Uncle Midas—who has a final resting place grander than Ulysses S.

[465] Ralph Gardner Jr. of The Wall Street Journal wrote in 2015: "The tomb, designed by John Duncan and based on an ancient Greek mausoleum, is relatively stark without being uninviting.