Graptolite

[1] Recent analyses have favored the idea that the living pterobranch Rhabdopleura represents an extant graptolite which diverged from the rest of the group in the Cambrian.

Due to their widespread abundance, planktonic lifestyle, and well-traced evolutionary trends, graptoloids in particular are useful index fossils for the Ordovician and Silurian periods.

[4] The name "graptolite" originates from the genus Graptolithus ("writing on the rocks"), which was used by Linnaeus in 1735 for inorganic mineralizations and incrustations which resembled actual fossils.

The colony structure has been known from several different names, including coenecium (for living pterobranchs), rhabdosome (for fossil graptolites), and most commonly tubarium (for both).

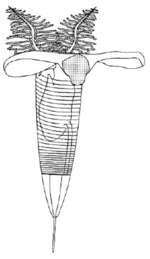

Early in the development of a colony, the tubarium splits into a variable number of branches (known as stipes) and different arrangements of the theca, features which are important in the identification of graptolite fossils.

Fuselli are the major reinforcing component of a tubarium, though they are assisted by one or more additional layers of looser tissue, the cortex.The earliest graptolites appeared in the fossil record during the Cambrian, and were generally sessile animals, with a colony attached to the sea floor.

As a nervous system, graptolites have a simple layer of fibers between the epidermis and the basal lamina, also have a collar ganglion that gives rise to several nerve branches, similar to the neural tube of chordates.

[6] Proper fossils of the soft parts of graptolites have yet to be found, and it is not known if they had pharyngeal gill slits or not,[7] but based on extant Rhabdopleura, it is likely that the grapotlite zooids had the same morphology.

[4] Since the 1970s, as a result of advances in electron microscopy, graptolites have generally been thought to be most closely allied to the pterobranchs, a rare group of modern marine animals belonging to the phylum Hemichordata.

One proposal, put forward by Melchin and DeMont (1995), suggested that graptolite movement was analogous to modern free-swimming animals with heavy housing structures.

Under this suggestion, graptolites moved through rowing or swimming via an undulatory movement of paired muscular appendages developed from the cephalic shield or feeding tentacles.

On the other hand, buoyancy is not supported by any extra thecal tissue or gas build-up control mechanism, and active swimming requires a lot of energetic waste, which would rather be used for the tubarium construction.

[10] The study of the developmental biology of Graptholitina has been possible by the discovery of the species R. compacta and R. normani in shallow waters; it is assumed that graptolite fossils had a similar development as their extant representatives.

The life cycle comprises two events, the ontogeny and the astogeny, where the main difference is whether the development is happening in the individual organism or in the modular growth of the colony.

Each larva surrounds itself in a protective cocoon where the metamorphosis to the zooid takes place (7–10 days) and attaches with the posterior part of the body, where the stalk will eventually develop.

The origin of this asymmetry, at least for the gonads, is possibly influenced by the direction of the basal coiling in the tubarium, by some intrinsic biological mechanisms in pterobranchs, or solely by environmental factors.

[12] Hedgehog (hh), a highly conserved gene implicated in neural developmental patterning, was analyzed in Hemichordates, taking Rhabdopleura as a pterobranch representative.

An important conserved glycine–cysteine–phenylalanine (GCF) motif at the site of autocatalytic cleavage in hh genes, is altered in R. compacta by an insertion of the amino acid threonine (T) in the N-terminal, and in S. kowalesvskii there is a replacement of serine (S) for glycine (G).

It is not clear how this unique mechanism occurred in evolution and the effects it has in the group, but, if it has persisted over millions of years, it implies a functional and genetic advantage.

They are most commonly found in shales and mudrocks where sea-bed fossils are rare, this type of rock having formed from sediment deposited in relatively deep water that had poor bottom circulation, was deficient in oxygen, and had no scavengers.

A well-known locality for graptolite fossils in Britain is Abereiddy Bay, Dyfed, Wales, where they occur in rocks from the Ordovician Period.

[14] The Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE) influenced changes in the morphology of the colonies and thecae, giving rise to new groups like the planktic Graptoloidea.

Later, some of the greatest extinctions that affected the group were the Hirnantian in the Ordovician and the Lundgreni in the Silurian, where graptolite populations were dramatically reduced (see also Lilliput effect).